All images by Stephanie Lee for RICE Media unless otherwise stated

Samantha* wakes. It’s 9 AM, and she’s already exhausted. Or maybe she’s still exhausted—the 30-year-old doesn’t quite know and hasn’t quite known when this bout of extraordinary exhaustion started.

Her morning routine includes standing by the coffee machine, repeatedly jabbing at it until the cup threatens to overflow with espresso. A minimum of four shots, if she’s awake enough to count.

But she never is.

It might sound like a crippling addiction to caffeine, like that one colleague who makes coffee their entire personality. But for Samantha, it’s more of a crippling dependency. Without excessive caffeine running in her veins, she wouldn’t have enough energy to start her day.

The keyword here is ‘start’. Come lunchtime, it’ll be another four to five shots of espresso and a few sticks of cigarettes before she has enough energy to continue with the second half of the workday.

Her fatigue isn’t something that’ll go away with a good ol’ night of rest. It won’t go away, even if she changes her job or makes time for self-care. This fatigue is chronic.

Warning: Battery Low

There’s a lot to unpack about fatigue that’s chronic, or chronic fatigue, as it’s referred to in this piece.

There are different types of chronic fatigue: It could be a result of a physical illness or one that manifests as a symptom of mental health conditions like Depression and ADHD.

Samantha initially thought her fatigue was caused by her dysthymia (chronic mild depression), but realised the fatigue remained even after she sought help for it. And then she found out from her psychologist that her chronic fatigue was piggybacking off her Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), like an unwanted 2-for-1 deal.

“I’m only recently aware that people… apparently have the energy to go through life and accomplish daily tasks without needing naps?” she remarks over a call, fresh from a nap. The nap has given her a temporary boost in energy, and she’s cheery and clear-eyed. For now.

“Like, what do you mean people don’t feel so tired all the time?”

The sensation of fatigue constantly weighs on her like a heavy blanket, pressing her down mentally, emotionally and physically. Brain fog sticks to her like her shadow, and she feels as though she’s in a perpetual state of waking up but never actually waking up.

She wakes up exhausted, goes about her duties exhausted, and crashes long before the day ends.

A close analogy would be spending the whole night charging your phone, only to wake up and realise the battery’s only juiced up to 60 per cent. And then it drains within the next two hours.

While freelancing, Samantha had the freedom to organise her days around her energy levels: nap, work, nap, work at night, nap. Now that she works fixed hours in an entertainment company, clocking in at 10 AM is a straight-up challenge.

Never mind that her morning alarm rivals a fire alarm—it’s as useful as a chocolate teapot. By the time she’s dragged herself out of bed, there’s barely enough time to beat the traffic lights and clock into work. She’ll still be late for work, anyway.

As a part-timer, she works a four-day week, ending work two hours earlier than her full-time colleagues every day. She’s been offered a full-time position before, but as much as her wallet desperately says yes, her energy levels make it a hard no.

“[My colleagues] would tell me ‘Oh you’re so lucky’ while comparing our schedules, but like you don’t understand. I spend the rest of the time laid out on the floor, barely conscious when I get home.”

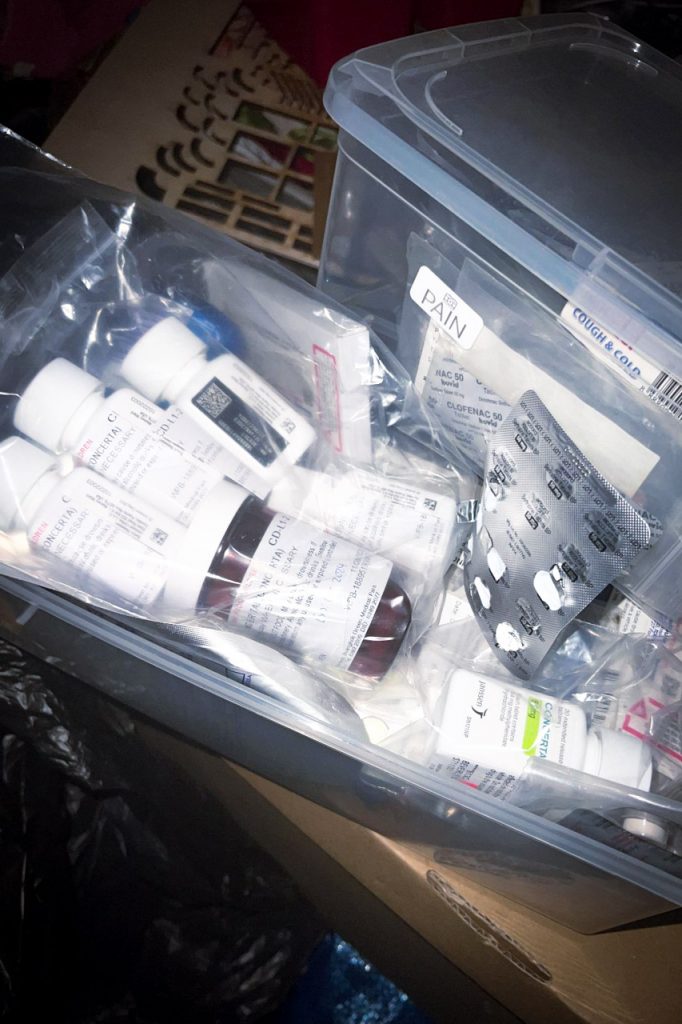

That’s not forgetting the excessive amounts of caffeine Samantha consumes to function on the job. Depending on the job’s demands, she sometimes stacks packs of menthol cigarettes and countless cans of Coke to keep her going. She’s well aware of the destructive effects her copiums have on her—heart palpitations are par for the course, and so are gastric pains.

“I have to choose. If I don’t have caffeine, I can’t function. If I drink it, I suffer the stomach pains. So should I just be sleepy and forgetful?”

Things took a slight turn for the better after Samantha was prescribed medication for her ADHD. Its main purpose is to regulate her brain chemicals, which, in the process, also allows her to channel her energy reserves the way an average person would.

She likens it to donning a pair of glasses; the (brain) fog lifts, she can see again, and she can do things using a fraction of the time she’d otherwise spend.

There’s one caveat, however. She finds that it loses effectiveness if taken too often, and thus has to ration the days when she can use them. In other words, her schedule revolves around her medication now.

If there are days that she needs to “get shit done”, she has to schedule days where she can “afford not to function properly” after. Her laundry goes undone, her dishes pile in the sink, and her pet rats go ignored in their cages.

Socialising with friends and family on her days off? An improbable dream at this point—she misses her parents, and her friends consider her more elusive than a shiny pokémon.

There’s only work, sleep, work, sleep.

And like caffeine, once the medication runs its course through her stream, her batteries run flat. Then she’s back to the floor again.

The Bare Minimum

While medication helps (somewhat) on most days for Samantha, 24-year-old Erica continues to run on empty.

She likens her fatigue to a wet sponge: You try to run it under water and get it to soak more water, but you can’t because it’s already full. You want to do more, but you’re already well over your capacity.

The popular spoons analogy defines each person as having a supply of spoons, where each spoon represents a unit of energy. Healthy people might use a spoon for perhaps going to school or work, for having social events at night, or for doing chores at home.

With Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), Erica finds that just getting out of bed alone takes up a spoon, brushing her teeth is another spoon, getting dressed is yet another spoon, and by the time she’s about to leave the house, she’s already out of spoons.

“At one point, I went a week without brushing my teeth,” Erica shares.

“I just couldn’t get up, brush my teeth and return [to bed]. My head was like, let’s just stay here, I’m tired.”

Her executive dysfunction also included episodes where she struggled with food. Lifting food to her mouth took too much energy, chewing took too much energy, swallowing took too much energy. It was easier not to eat at all.

It was and still is, easiest to lie in bed all day in the darkness of her room. Much like a bear in hibernation, trying to make it through winter.

Except it’s a permanent summer here, literally and figuratively. Nature is thriving, and the world is moving ahead while she hides away.

“This is where I do everything!” she says with a flourish as we enter her bedroom.

It’s an exaggeration but not a far-fetched overstatement. From where she sits in the middle of the bed, Erica files reports for her internship, plays games on a console, and doomscrolls. She does her makeup by a hanging mirror on her door. When she needs to, she pushes her things on her floor to a corner to work on her cosplays.

I say ‘things’ because it’s hard to even begin identifying the shapes and masses piled up across pretty much every visible surface of her room.

In this regard (beyond the fatigue), Samantha and Erica are similar. Both of them describe their living conditions as a perpetual mess; neither of them can bring themselves to make it orderly.

For them, cleaning up isn’t a single action. Thinking about cleaning up is step one, and hyping themselves up to clean is step two. Getting to their feet to begin cleaning is step three, followed by addressing one pile of things, sorting out what’s in it, figuring out where things should go, and clearing out items to make space to pack. The list goes on.

The brain splits one task (cleaning) into multiple little subtasks, all of which stack up and become an insurmountable chore. If she’s lucky, Erica says she’ll sort just one pile. It’ll be months before she’ll have the spare energy to attempt packing again.

Like all Asian parents, her parents berate her over the state of her room, as they do about her lack of exercise, among other things. She takes it lying down, literally. There’s nothing she can do about it.

“I want to [be able to do the things I need to], I really want to,” she sighs. “I just don’t have the energy.”

Often, we don’t realise what we consider ‘simple’ tasks are monumental uphill challenges for people with chronic fatigue. Sisyphus deserved his punishment, but people with chronic fatigue are forced to move boulders daily just by waking up, serving terms for crimes they never incurred.

The term ‘bare minimum’ gets thrown around often, especially in the workplace. In an Asian and capitalist environment, much of our perceived worth is tied to our productivity.

‘Bare minimum’ becomes a justification that when a person fails to meet expectations. They’re then deemed ‘lazy’.

‘Why so lazy?’

‘Lazy’ is a landmine.

“The general definition of lazy is someone who has all the ability to do things but just doesn’t want to,” Erica fires off.

“That’s the thing, we don’t have the ability to do things even though we want to.”

Though Samantha and Erica use the term on themselves (whether in jest or out of self-deprecation), it hurts when someone else calls them lazy. Slapping the label across their faces steamrolls all the effort they put into staying alive.

Sometimes, the insults are less direct.

“You’re so lucky, you drive to work” and “Wow, you’re always taking Grab” are some of the common sentiments Samantha gets from her colleagues, past and present.

The hidden questions: Why don’t you just take public transportation? Are you that lazy?

She could explain to them that taking public transportation with all its external stimuli severely depletes her limited energy reserves. She could explain that if she took public transport to work, she wouldn’t have enough energy to get her back home. She could explain her 30-odd-dollar Grab fare is a financial sacrifice she makes to show up and function at her job.

Samantha is resigned to her fate. “They don’t understand, and they won’t understand, so why bother trying to explain?”

It’s hard to begin empathising—how can a person who’s never had to ration energy begin to fathom what it’s like to have to choose between two exceedingly simple actions, knowing they won’t have the energy to execute the other?

Every day, Erica and Samantha have to actively choose what to focus on: Do they focus on their work, their family, their social life, and their self-care? Whichever one they prioritise, they have no choice but to sacrifice the rest.

Samantha chose to prioritise her job over her parents, whom she doesn’t live with and hardly sees. They’d text her asking to meet up, and she’d apologise for being busy with work. It’s an excuse and she knows it—but she also knows she doesn’t have the capacity to avail herself.

Her friends don’t see her for months on end, either. Occasionally, she gives in to socialising, overextending herself in the process and rendering herself useless for days after.

“I don’t have the energy to accommodate the people who want to see me, and my parents suffer the most because of that,” she says.

“It makes me disappointed in myself, like why can other people do what I can’t? Why is everyone doing so much better? Why am I so lazy?”

Self-acknowledgement and acceptance take time. Samantha calls it an ongoing process to acknowledge that she has less energy than an average person and not beat herself up for it.

In the same vein, she’s also come to learn that a lot of the people she previously thought of as lazy also had other priorities going on in their lives—responsibilities and burdens that she wasn’t aware of.

Empathy: A Catch-22

Grief also forms a huge part of chronic fatigue. There’s grief over the perceived loss of liberty, the loss of freedom and the loss of flexibility. Comparison is the thief of joy, yes—but when you’re robbed of the ability to do what everyone else easily can, it fucking sucks.

There’s so much yearning in the way Erica and Samantha talk about their fatigue. At its core, they just want to be able to function as a normal person would. It’s something they’ll have to live with. But on the bright side, it can get easier. And it has.

One good thing about the pandemic is the introduction of flexible working hours and hybrid working. It’s made it easier for people with chronic fatigue to plan their work hours around their energy levels. Working from home also means energy saved—energy that would otherwise be wasted enduring crowded commutes, working under harsh fluorescent lights, and socialising with colleagues.

Employers can make the accommodation if they’re aware of chronic fatigue. But in order to have a greater awareness of chronic fatigue, employees would have to disclose their condition—and all disclosures come with a risk of backlash.

Who’s to say a replacement can’t be hired, especially when that’s easier than accommodating a lesser-known ailment like chronic fatigue? As it is, Samantha couldn’t convert to a full-time position at her current job because they weren’t able to make adjustments to her working hours.

Life on Full Battery

The past few years have seen an active increase in campaigns for better mental health awareness in Singapore. Companies are now recognising that mental health cannot be an afterthought.

Treating people like cogs in a system may have worked in the past, but a greater emphasis on empathy and compassion slowly changes mindsets in the workplace. Perhaps, with time, people won’t have to feel penalised for a condition they can’t control.

Control over their own bodies and minds is all Samantha, Erica, and other chronically fatigued Singaporeans will ever want—but can’t. I ask if they’ve ever wondered what life would be like if they didn’t have chronic fatigue.

Erica immediately babbles: “I’d be able to get so many things done, like I’d actually be able to talk to and meet up with friends; I’d have the energy to actually have hobbies and do the things I enjoy.”

“I keep telling people: God had to nerf me because I was too powerful.”

Samantha’s response is more sullen.

She doesn’t dare to imagine a life she can’t have.