This post was first published Oct 17 2019.

Are schools doing enough for sex ed?

Having been a teacher for 25 years, my motto has always been: remove cringe and demystify. I begin sex ed classes by getting everyone to say “penis” and “vagina” aloud three times without giggling.

This way, I can proceed with the subject matter, well, matter-of-factly.

Reading the news of late (namely cases of uni students with sexual assault or peeping tom charges), I do wonder if there are many who simply lack the guidance with regards to consent—to the point that even universities have to create a module on this. My central concern is that in our country, porn has definitely created too much objectification and unrealistic expectations, shaping impressionable minds who become fixated on sexual gratification while not respecting boundaries.

That said, I also wonder if our education system has come short of educating our kids.

The syllabus attempts to be extensive, covering anything from biology to consent. It begins with teachers attending hours of pre-classroom seminars ranging from theories to cringe-worthy role-playing.

Yes, we have to act out possible scenarios of our 17-year-old charges in sexual contexts ranging from casual encounters to relationship transitions. An example: Boy A asks Girl A if they can have sex after their third date. Or what the appropriate age of consent is if you meet a date on Tinder.

Imagine your seemingly prudish teachers turning themselves into teenagers negotiating sexual tension. It isn’t any wonder that it’s hard to take these sessions seriously, at least going by the uncomfortable chuckles all around.

Most teachers are pretty much stoic when delivering sex ed lessons because they know they are mandated by the Ministry of Education. Hence they don’t question these lessons’ validity or relevance.

There are, however, a few younger teachers who have shared with me their reservations about how lessons are conducted so we modify them according to class culture or contextualise them with modern references. For instance, how Instagram seems to encourage latent sexualisation of teenagers, or Tinder becoming rampant amongst teens.

And then there’s the application. We go into class announcing that we will spend the next three lessons of civics on sex education to the mixed response of hormonally-charged whooping boys to the squeamishly protesting girls. A third segment would rather just complete their math tutorials.

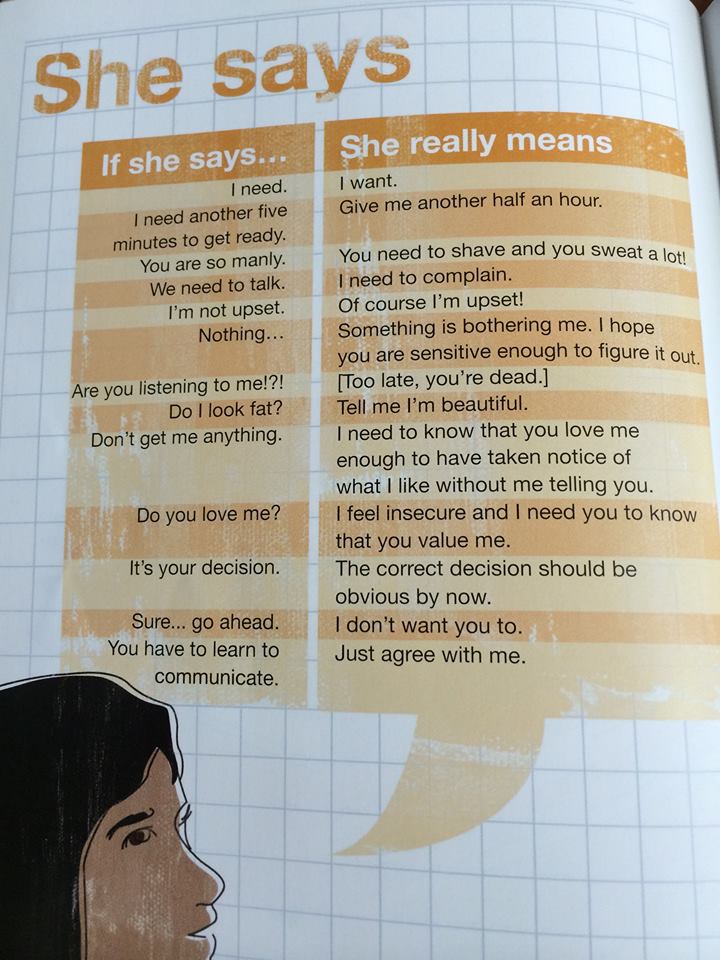

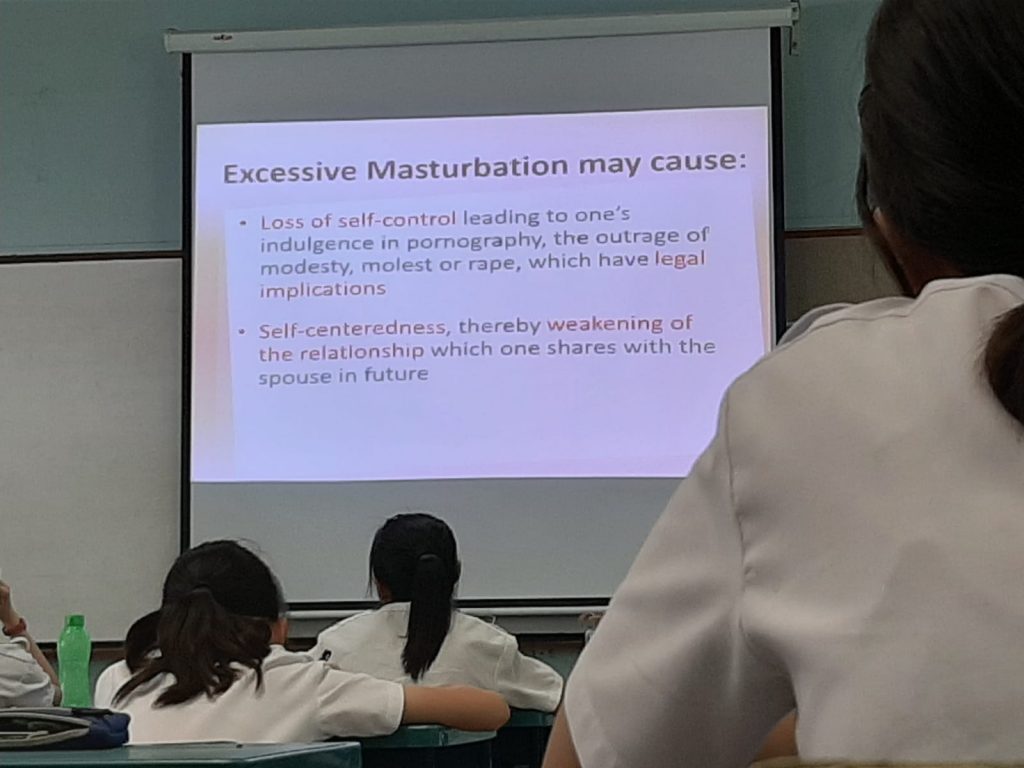

More often than not, this inevitably ends up turning into a case of expectations versus reality. Rather than quizzing their teachers about techniques or personal sordid experiences, the syllabus presents students with informative sources for HIV/STD treatment and a panel of sexperts pre-approved by MOE to preach about the ramifications of pre-marital sex.

Such a panel could consist of medical representatives from MOH, a married teacher with kids, a lawyer, and a school counsellor. The result: lessons about contraception usage without actually showing how or where. Often, it is clinical and somewhat preachy. Included are videos (that somehow draw unintended humour) produced by private organisations about youth who end up with unwanted pregnancies or diseases.

Across all content, the message is clearly abstinence. It isn’t surprising that after we get them to fill in feedback forms, some of my students say they were bored, disappointed, or preferred to Google or Youtube their queries.

I once asked my form students to blink at me as I looked around the class to survey who had had sex before. Some girls placed their fingers around their eyes to pry them open, adding that they had enough on their plate to worry about—like their A levels, to start—than to have sex.

In fact, when I tried to explain certain curious questions about what constituted sex (like hand-jobs or fellatio), my young colleagues observing at the back of the class said all they saw were the backs of some kids in mortified jolts.

In separate sessions by gender, the boys shared more adventurous questions and encounters, including boys I didn’t teach because, to quote, “(Their) teacher looks like a 50-year-old virgin”. One even mentioned how he met an older woman online who had propositioned him.

In contrast, the girls would say that sex is “gross” and that boys who watch porn are “er xing” (disgusting). It didn’t help that some boys proclaimed in class that they’d rather date their right hands. I just chalk it up to boys being culturally conditioned to sexualise their experiences at a much earlier age.

So it seems there is not only a gender divide in sexual education, but also a cultural one. The more conservative or religous ones would often shun having such conversations, let alone experience sex. Religions like Islam or Christianity clearly restrict pre-marital sex, so it seems irrelevant to be discussed among teens who subscribe to their religious principles.

Usually, it’s something like “we’ll cross that bridge when we are about to be married”. As for students from more Asian-conservative families, they don’t discuss the taboo subjects of sex or related topics at home, so they’d rather ask their peers or go furtively online, often stumbling into porn sites.

Speaking of difficult conversations, the sex-ed curriculum excludes possible questions about the LGBTQ+ community. It assumes that teens do not face sexual confusion at that age, though my exchanges with these kids have revealed the contrary.

For every batch of students in a 2-year cycle, there would be one or two asking or sharing about their inner struggles with their sexuality, either with disapproval or shame. So much so that I have become the vessel for where gay angst is unloaded, even for students I don’t teach.

They tell me it’s because I seem “chill” and don’t judge. I can’t help but feel sorry for these kids who carry this burden of their secret shame while dealing with their school syllabus’s implication that they simply don’t exist.

I recall how during a lecture session on sex ed with a panel, a question on homosexuality was written on paper during the Q&A portion. A speaker promptly mentioned the legalese of 377A, dismissing any further exchange on the matter. I wondered how these students, with their private struggles, felt at the time; whether we were doing enough to help them.

Is the teacher’s role simply to dispense information or to guide them in making better choices? Or is sex ed just another three hours of the syllabus we need to fulfil without following up?

As it is, teachers themselves hesitate when asked in school because discussing homosexuality already causes worry about violating some MOE by-laws. So at most, it is implied as a psychological problem for the school counsellor. Other teachers and principals even declare it wrong or illegal. Personally, I have only managed to speak to students about it, not in my capacity as a teacher, but as an actual adult, sometimes online after school hours. Being out to them as queer also eases their trust and comfort level with the subject matter.

There are school counsellors assigned to deal with adolescent emotional volatility, and to a large extent, they are reliable sources, a relief even when teachers can’t deal with certain questions. But the unspoken stigma remains that only troubled teens are counselled.

So every time I read about a promising student who offends, I wonder if they grasp the notion of consent or have even dealt with their inner demons while in school. If parents can’t manage their questions, how much more can their teachers?

During parent-teacher meetings, a few parents will mention their anxieties about their child’s boy-girl relationship dynamics, which I assume includes sex or petting. My stand as a form teacher remains that I am a distant mentor who can only advise them to keep their grades up, only intervening if they violate school rules. What they do beyond campus is out of my purview. This is why I think that where sex ed is concerned, teachers are also restricted to keeping their professional distance so the whole subject becomes mere science.

We wish we could be more personal in our approach and include conversations with the kids about their deeper issues. But we are also constrained by time and syllabus.

And while we hope we could outsource this entirely to professional vendors equipped with the required expertise (read: comprehensive, and not just ‘abstinence-based’ sex ed), this opens another can of budgetary constraints, not to mention the red tape which often binds.