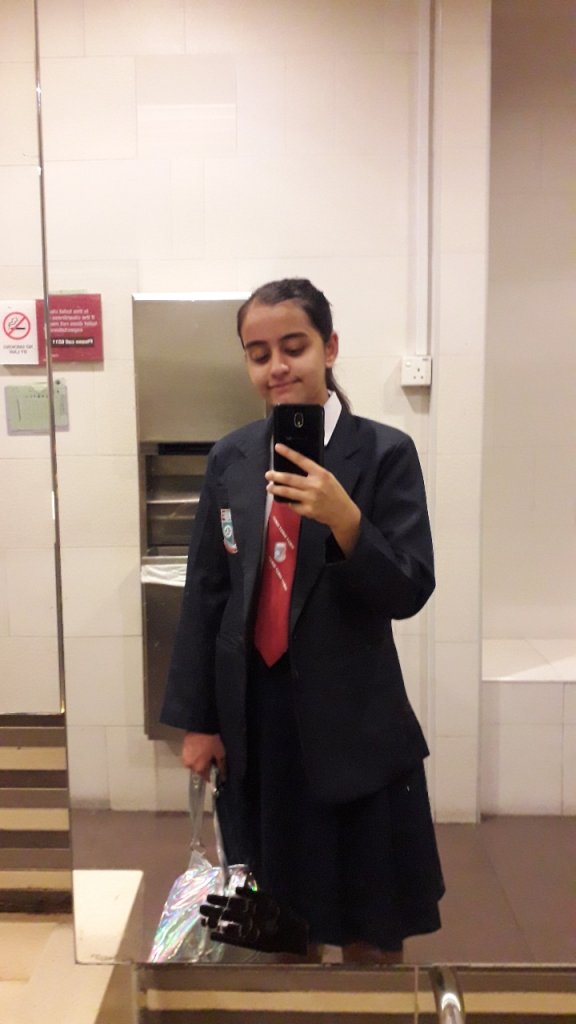

Top image: The writer in 2010, when she was a Primary 1 student at CHIJ Kellock.

As the aeroplane made its slow descent towards Singapore, I watched the island city beneath me unfurl like an emerald flower in bloom. It was thick with greenery and rain—a far cry from the dry yellow-brown desert I spent the formative years of my life in. There it was, amidst an expanse of pale blue: Singapore, my home country.

I had returned to Singapore, the country of my birth, after nearly a decade living abroad in the United Arab Emirates. I knew Singapore only through the trips we took back home every few years, where we spent a few weeks living at my uncle’s house in Pasir Ris and exploring the city before returning to Dubai.

When I moved back to Singapore for good, it became a symbol of the identity I always craved. I am a third-culture kid—I grew up in a culture different from the one my parents grew up in—and because of that, I have always felt deeply lost when it came to identity. I have never felt particularly Pakistani, or Emirati, or even Singaporean.

After so many years of feeling disconnected from my cultural identity, I made a decision: I would become a “true” Singaporean. And although Singapore didn’t feel like home, I was determined to make it one. I was willing to do anything to feel like I belonged somewhere.

Treated like an outsider

The first day I started at secondary school, my form teacher made me stand in front of my Secondary Three classmates and introduce myself. There I stood, in my tightly-combed ponytail and navy-blue knee-length skirt, my heart beating with excitement. For a few minutes, I looked just like everyone else, and I was treated as such.

Until I began to speak, and the air in that classroom instantly changed. From then on, I was treated differently.

All the symbols of “Singaporean-ness” that I thought mattered–the bright red Singaporean passport, the fact that I had been born in a Singaporean hospital, the pride I felt towards Singapore—all of it fell away like insignificant specks of dust. None of it mattered because I was an outsider in the way I spoke.

I didn’t speak like the Singaporeans who had spent all their life in the country. I didn’t understand the Singlish spoken around me. I constantly had to search up and memorize the meanings of Singlish words to keep up with my classmates. And no matter how many times I repeated that I was Singaporean, my schoolmates continued to refer to me as a foreigner.

The first time I felt like I belonged

A little over two years later, I stood in the thick swelter of a Tai Seng chicken rice shop—the heat assuaged only by the ceiling fans creaking above me—and absentmindedly rattled off my lunch order to the uncle standing behind the cash register.

“You want dabao?” he asked.

I paused, racking my brain to remember the meaning of “dabao”. I vaguely recalled a food delivery website with the word “dabao” in it, and so with that clue, I quickly concluded that the uncle was asking if I wanted to take away the food.

As I walked away from the stall, armed with fragrant bags of chicken rice, it hit me that the uncle assumed—without me having to say it—that I was Singaporean. He spoke to me in Singlish! In only one conversation, he decided that I was Singaporean! Unbeknownst to me before this moment, I had finally gained the magical ability to speak Singlish!

This was the first time since I returned to Singapore that someone assumed, without me having to tell them, that I was Singaporean.

This was the first time in the 18 years of my life that I felt like I belonged.

Singlish and Belonging

My experience with Singlish made me realize how important language was to the Singaporean identity.

In his book The Guidebook to Sociolinguistics, Allan Bell writes of the social implications of language in Paraguay:

Paraguay has two national languages—Spanish and the indigenous Guaraní. Guaraní proved to be the language of intimacy, while Spanish is for acquaintances. Guaraní is the language of the country, Spanish is more likely in town. So what language do you speak with a barefoot woman? Guaraní, of course. With an unknown man wearing a suit? Spanish. And with a woman wearing a long skirt and smoking a big black cigar? 89 out of 91 people said Guaraní.

Much like Guaraní, Singlish is the language of intimacy because it is a language few outside the region can comprehend and speak. Singapore is a country populated by various races, religions, and languages, and Singlish provides an intersection where Singaporeans can put aside their differences and rest upon a shared linguistic identity. In a busy, globalized world, Singlish is a way for Singaporeans to identify with each other and feel a little more at home.

Nonetheless, Singlish being such a significant part of the Singaporean identity may be a double-edged sword.

Language is such an integral part of society and culture—it is the first step to connecting and communicating with each other. Even so, language should not be the sole marker of a “real” Singaporean”.

What happens to a Singaporean who is unable to speak with a Singaporean accent or is unable to understand the nuances of Singlish? What happens to the foreign national who has spent their entire life in Singapore? Does not speaking Singlish make them any less Singaporean?

Why did I only feel accepted as Singaporean when I spoke like everybody else?

Perhaps this is a product of Singapore’s famous obsession with order, or its collectivistic society, or maybe our tendency to be wary of the unfamiliar. I have observed that, often, when we stumble upon people who don’t behave according to our preconceived notions on who a “true” Singaporean is, we knowingly or unknowingly treat them as outsiders.

The days of neat, clearly demarcated boundaries of identity are rapidly leaving us behind. We must collectively expand our definition of what a Singaporean is, rather than limiting it only to certain races, religions, backgrounds, languages, and accents. We must embrace our differences in speech, behaviour, and beliefs, rather than dividing ourselves according to who is Singaporean “enough” and who isn’t.

It is undoubtedly a beautiful feeling to be able to speak in a “traditionally Singaporean” way. To this day, I feel such joy to be able to converse with Singaporeans around me in a way that is familiar and comforting to the both of us. I love being able to slip easily into the swift, unflinching sounds of Singlish and no longer have to be so aware of how different I sound compared to others.

Still, my identity as a Singaporean should have been accepted years ago—simply on the basis that I was Singaporean through birth and that my mother’s family grew up here and that I loved Singapore—rather than on the basis of my accent or where I grew up. I should not have been treated as an outsider or had my identity as a Singaporean devalued just because I spoke differently.

The truth is that I was Singaporean when I still lived in Singapore, and I was Singaporean even after I left.

I was Singaporean long before I gained the ability to speak Singlish.

And I was Singaporean long before someone listened to me speak and decided, finally, that I was worthy of acceptance. That I was worthy of belonging.