Top image: Author’s family at Bukit Timah Hill

I was at my community centre some time last month when a clueless looking lady in a green uniform approached me with her mobile phone. She asked me what language I spoke, and if I could tell her client on the phone that she had delivered their order. I said no problem and got on the phone with her supposed client who only spoke English—except the call was from the delivery platform instead.

The platform staff said the lady’s account had been suspended as she failed to upload her COVID-19 test result for the day. I translated this to the lady, who was spurred into surprise. She told me she had already uploaded it last night with the help of her daughter, but the platform staff insisted they did not receive it. The lady wouldn’t be able to accept new orders from now on until she successfully uploaded her test result, the staff added bluntly.

Before hanging up, I told the platform staff that their delivery partner (the woman who approached me) could not communicate in English and was turning to strangers for help. I asked them to escalate this to their managers and consider having staff equipped to handle queries in other languages.

The translating experiences I should include in my LinkedIn profile

My parents are English illiterate. It was part of my growing up years to be their ears and mouths. When I found English letters addressed to them, I’d automatically translate the content. When they were too busy to listen, I’d write little translated notes on the side of these letters. Similarly, I’d make marks near where they need to sign on school consent forms and fill up the rest on my own. When dining out, I’d translate all the food options, especially when only English menus were offered and no one in the serving crew could speak their language.

I have heard my parents get asked, “why don’t you speak English” so many times in my life that I lost track. I don’t remember ever getting upset about having to translate for my parents, so I don’t understand why others would be bothered when I am the one doing the translation.

Looking back, I should put these 20 odd years of translating experiences on my LinkedIn so I could start commissioning companies to make their services more linguistically inclusive. Still, only after becoming a working adult, I realized how much my parents were missing out when I was not around.

They wouldn’t be able to enjoy a blockbuster without subtitles, join a local cultural experience, or venture into the food and drink selections beyond where we live. If you are skeptical, go around without speaking a word of English for a day and you will know.

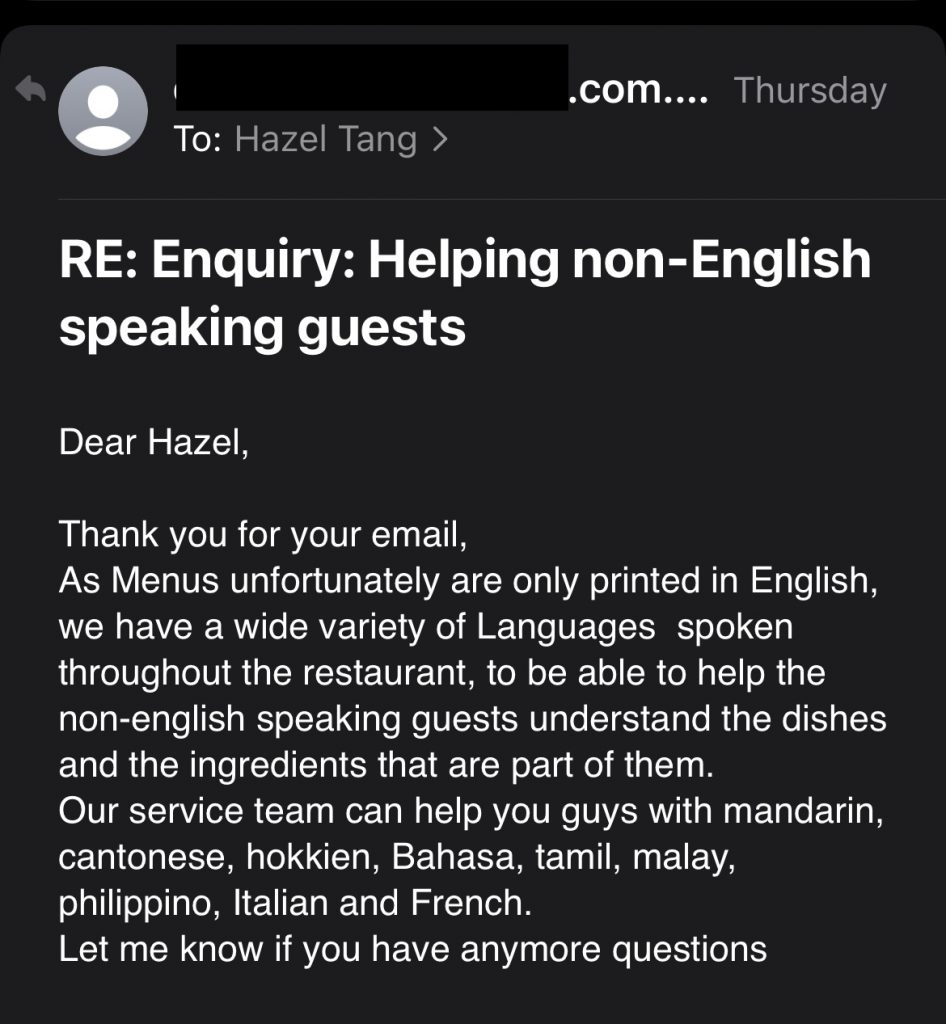

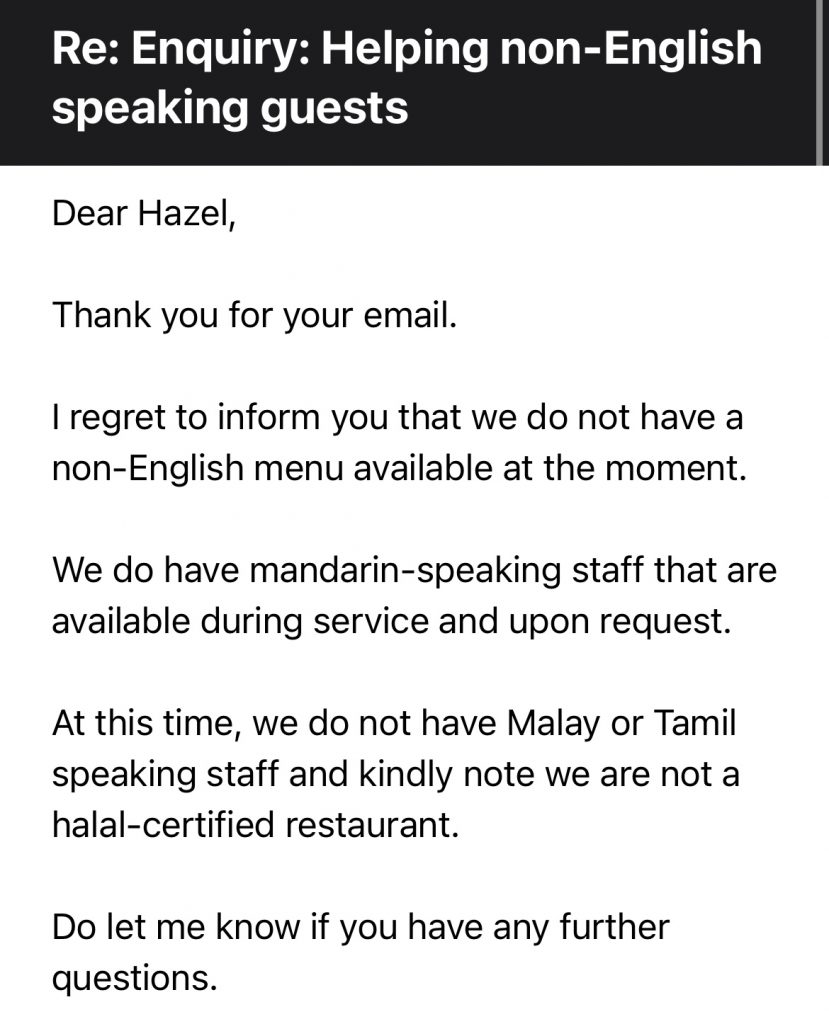

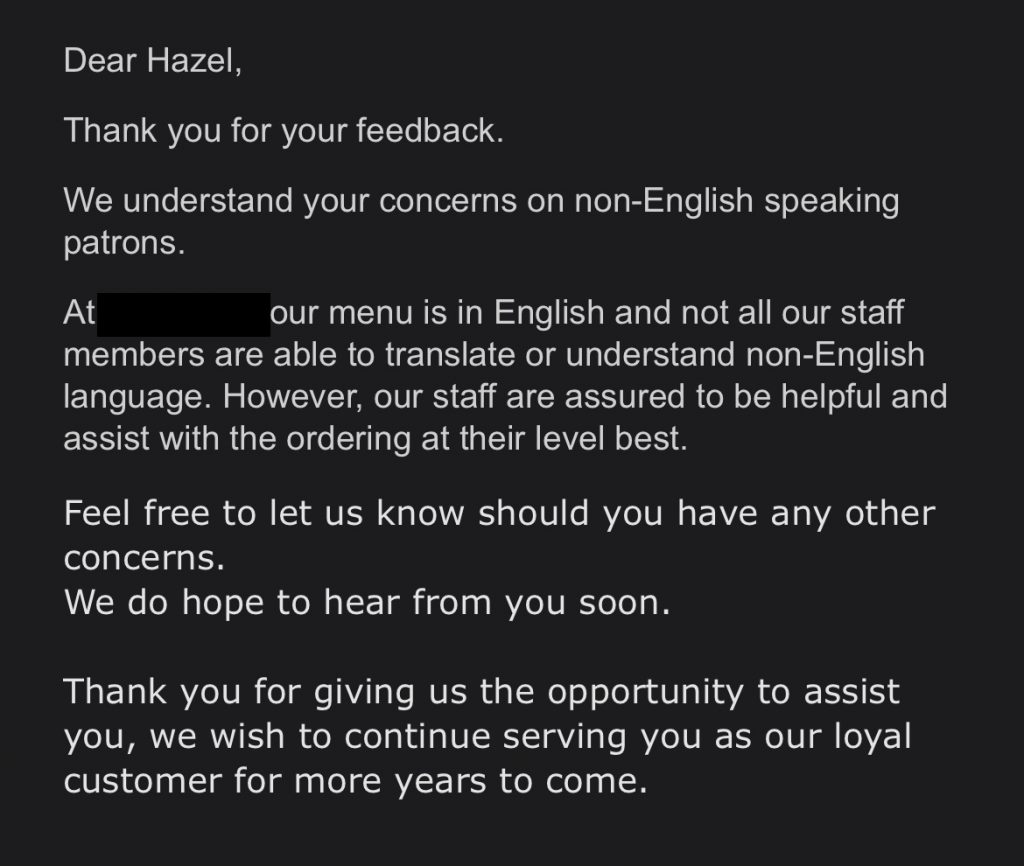

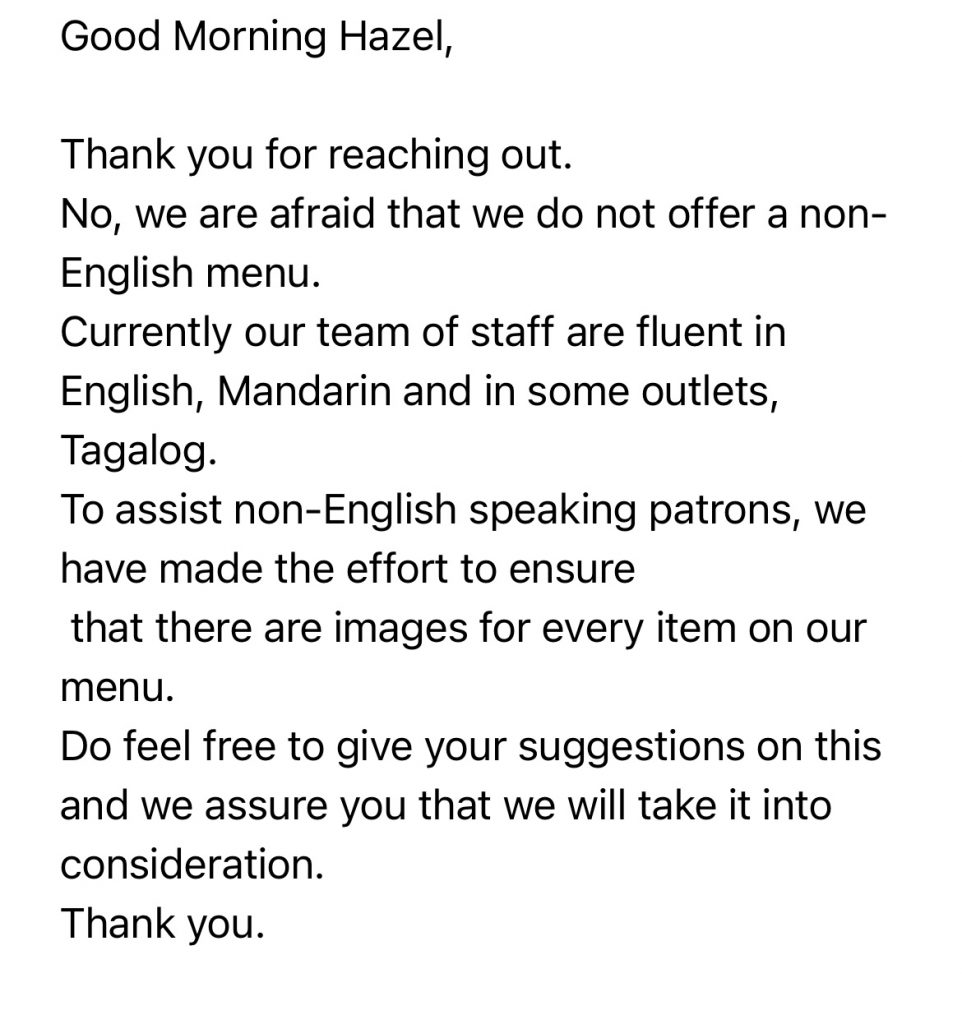

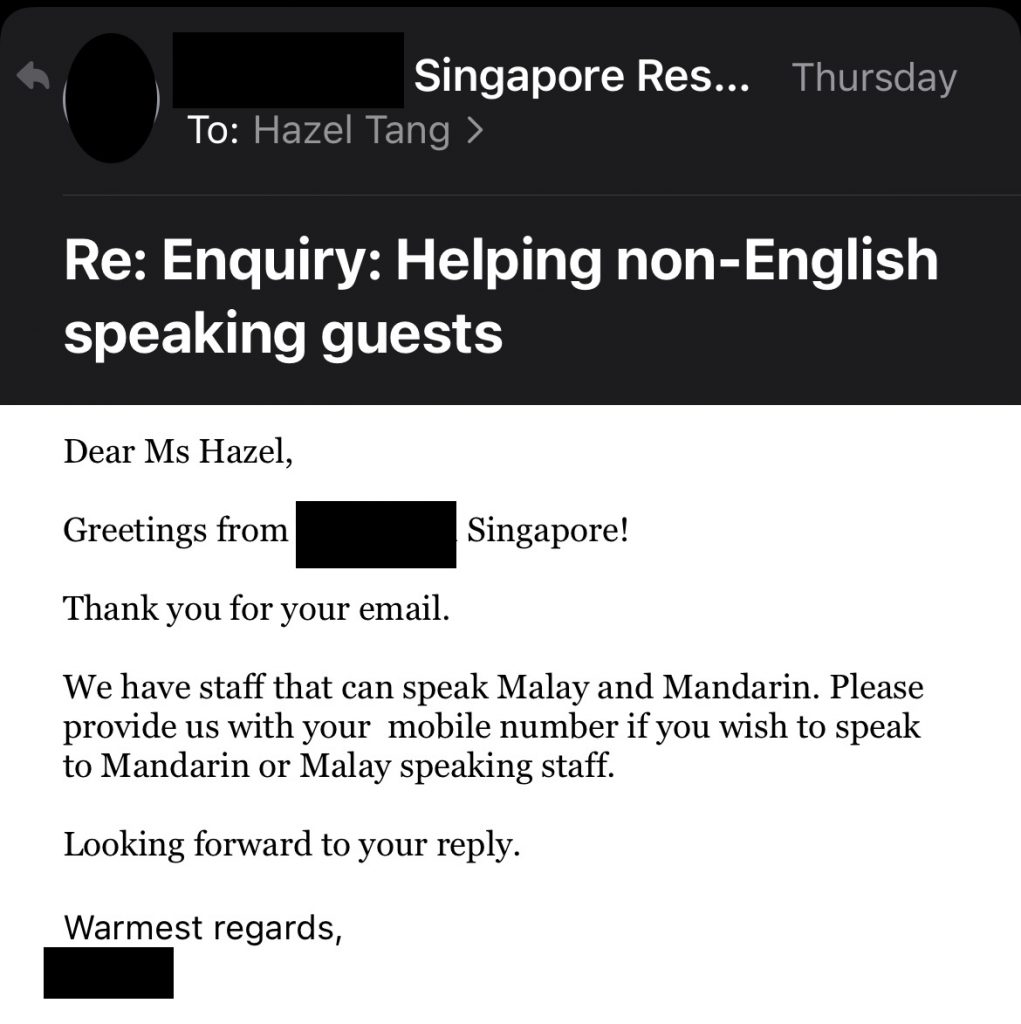

To better understand how different companies fare in translated options around Singapore, I emailed close to 50 restaurants and cafes. Many do not offer non-English menus, and they are also not confident in serving non-English guests. Interestingly, some offered their menus in foreign languages in accordance with the cuisine they serve. I am glad there are a few exceptions. Their replies are as follows. Feel free to guess who they are.

Language as a social class nametag

Under British colonial rule, Singapore was racially and linguistically fragmented. It was only after World War II that schools were gradually brought under government control, and a language was to be determined to facilitate communications among the diverse population.

Malay was once considered to be the lingua franca given our hope to merge with Malaysia. That was ultimately replaced by English in the wake of the nation’s independence for reasons inextricably tied to our founding prime minister Mr Lee Kuan Yew.

In his book, My Lifelong Challenge: Singapore’s Bilingual Journey, published in 2011, Mr Lee wrote, “How would Singapore make a living… trade and industry were our only hope. But to attract investors here to set up their manufacturing plants, our people had to speak a language they could understand. That language had to be English. For political and economic reasons, English had to be our working language. This would give all races in Singapore a common language to communicate and work in.”

By 1987, the mother tongues of the three major ethnic groups, Chinese, Malay, and Tamil, would be taught only as an academic subject with English as the primary instruction medium. The move officially marked the end of vernacular schools, meaning society would now be divided into the English and non-English educated.

Still, our “survival driven” education policy is so successful that those not fluent in English are subsequently excluded from the majority. Over time, they are pigeonholed as less educated and from a lower social class. The most uncomfortable part is some believe that not being able to speak English is a trait that can be passed down.

Once, I came down with a bad ear infection, and being concerned, my mum couldn’t wait to tell my doctor what happened. I immediately knew that the doctor could not fully comprehend what my mom said given her confused expressions. So, I decided to take over and repeat everything in English.

“Oh, your daughter can speak English?” the doctor asked. I thought she was rude, but my mom, oblivious or perhaps used to what society thinks about people like her, bashfully replied, “Yes, because she goes to school.”

Indeed, my parents don’t have a degree, and they have been blue-collar workers all their lives. Still, what couldn’t I get over was why language—a mere tool of communication—was being turned into a social class nametag? Those who “wear it” are considered as belonging to “a higher status” and have the right to belittle those who don’t. It’s ironic we take pride in Singlish but unconsciously ostracize languages other than English.

We are losing our “bilingual competitive edge” not because we don’t have a conducive environment to incubate our fluency in both English and our mother tongue, but because all along, our meritocratic upbringing got us thinking that knowing English is the only “way to survive” and enter a better social class.

Where do we go from here?

I am not sure whether the English language or sincerity and respect matter more when it comes to getting along with people who don’t speak the same language as you. I have seen my parents not only function but thrive in their workplaces without knowing English. So what I think is stopping Singaporeans from grasping this is their mindset. Speaking English helps practically—and I don’t deny that—but it should not be seen as a status symbol.

I hope my child will live in a society where people learn languages or subjects because they genuinely love them, not for survival, face, or status. But for this to be achieved, we need to start by showing kindness to the English illiterate in Singapore.

When I looked into what services were available for non-English speaking customers at the variety of establishments I emailed, I found that many performative actions are taken with little follow-up from the company’s end.

For example, the delivery platform I mentioned at the beginning of this story was more preoccupied with asking me whether I would name them or compare them to other delivery platforms than giving me a clear response.

After reassuring them that this would not happen, the platform replied, “we provide help in English, Malay, Mandarin, and Tamil through our main support hotline and physical driver/delivery centre”. In addition, their message service is “automatically translated to ease communication between our driver and delivery partners, as well as our users.”

When I asked whether their delivery partners were aware of the measures in place and what the recommended steps were for when a similar incident happened again, the platform stopped replying. I was left confused—they had a corporate structure in place to help but had not thought of how this would work on the ground.

Maybe, what we need is more awareness. Thanks to various efforts like the “Speak Good English” campaigns we grew up with, English is becoming increasingly pervasive. And while I am not against such government endeavours, I do believe we can petition to improve our standards of written and spoken English while also cheering on those who have not acquired the skill just yet.