A few minutes past our appointed Zoom meeting time, Mdm Rani’s smiling face and bright pink tunic blossom into view on my laptop screen. On the sofa next to her is Felicia, our liaison at AMKFSC Community Services. “Sorry we’re late,” the latter explains. “We had some trouble setting up.”

I’m here to interview Mdm Rani, a housewife, about the difficulties of falling on the wrong side of Singapore’s digital divide. We had originally arranged to meet at her home, a rental flat in Ang Mo Kio, but the spiking Covid case numbers forced our meeting online.

The irony of our situation—discussing digital exclusion over a video call—is not lost on me, but as I ask a few questions to warm us up, I realise nothing could have better brought out the challenges she faces.

First, we are taking the call on Felicia’s laptop. Mdm. Rani does not have one of her own, and her children’s laptops, both of which were obtained via assistance schemes, are lagging badly.

Second, while Mdm. Rani has used Zoom several times before—she attended a virtual church service just that morning—she doesn’t really know how to use it in any meaningful sense.

She does not know how to start the programme, join a call, or what her login details are. Although she has a Zoom account, her daughter set it up for her, and she doesn’t even know the email address used to create it. (At least the internet is behaving today; the connection in their home can be unstable.)

While she is unquestionably capable in many respects—Mdm Rani is an enthusiastic community volunteer and can cook one hell of a curry—navigating the digital realm remains a struggle. In general, anything beyond Whatsapp or watching videos on Youtube is out of her comfort zone. She times any laptop use around her children’s schedules to ensure they are at home to help her.

“If [my daughter’s] not around to help, I don’t know how to use Zoom, so I just miss my church service,” she tells me.

“Like if the Internet connection is not good or the camera is not working, or I’m on mute … They say just press to unmute, but I don’t know how. I need to learn a lot of things.”

How the digital divide threatens social mobility

Mdm Rani is just one of thousands who risk being left behind in Singapore’s pursuit of Smart Nation-hood. While Singapore’s digital coverage ranks amongst the highest in the world, a gulf, known as the digital divide, sits between digital haves- and have-nots.

This distribution splits along existing lines like income, education, age, and language, with low-income students and adults, the elderly, and migrant workers amongst those at greatest disadvantage.

Low-income families, for example, are overrepresented amongst the digitally excluded. While Internet coverage is almost universal in Singapore—just 2% of resident households lack a connection at home—8% of families in rental units, surveyed by the Singapore Longitudinal Early Development Study (SG LEADS), did not have one.

Similarly, it found that 44% of families in rental households do not have a computer or laptop, compared with 11% nationally. (Amongst those living in private condos or landed properties, the rate falls to 4%).

A 2021 paper on universal digital access co-authored by several academics, including Professor Lim Sun Sun of SUTD, Associate Professor Irene Ng of NUS, and Senior Lecturer Natalie Pang of NUS, elaborates on the depth and complexity of challenges faced by different groups. Of these, cost and affordability are just one aspect.

Older rental flats, for example, may lack the infrastructure for the installation of fibre-optic cables. Seniors—if they even have smartphones—may not be sufficiently digitally literate to use them independently. Migrant workers, on the other hand, might own defective or outdated smartphones, or lack the English-language skills to use apps like email and mobile banking.

Compounding all this is the potential for the digital divide to not only perpetuate existing inequalities, but worsen them.

Without a functioning computer, Internet access, and literacy skills, children risk falling behind their better-resourced peers in school; their parents might struggle to apply for courses or jobs.

Digital access, the paper’s authors insist, is not only necessity, but a “vital conduit for social mobility”.

While they acknowledge the existence of many assistance schemes, both from the government and charity sectors, they contend that Singapore’s digital transformation plans must be made “more progressive”.

For our much-hyped digital transformation to be fair and effective, our ambitions must be matched by our efforts to help the most digitally vulnerable.

“Otherwise,” they argue, “in a world where inequality is already high, digital inequality will become a source of social divide and an impediment to social mobility. “

“With digital access now a necessity, high speed internet connection should become a public utility like electricity and water.”

The invisible necessity—digital access as a need

Central to this is the recognition that digital access, in today’s context, is a need and not a ‘nice-to-have’.

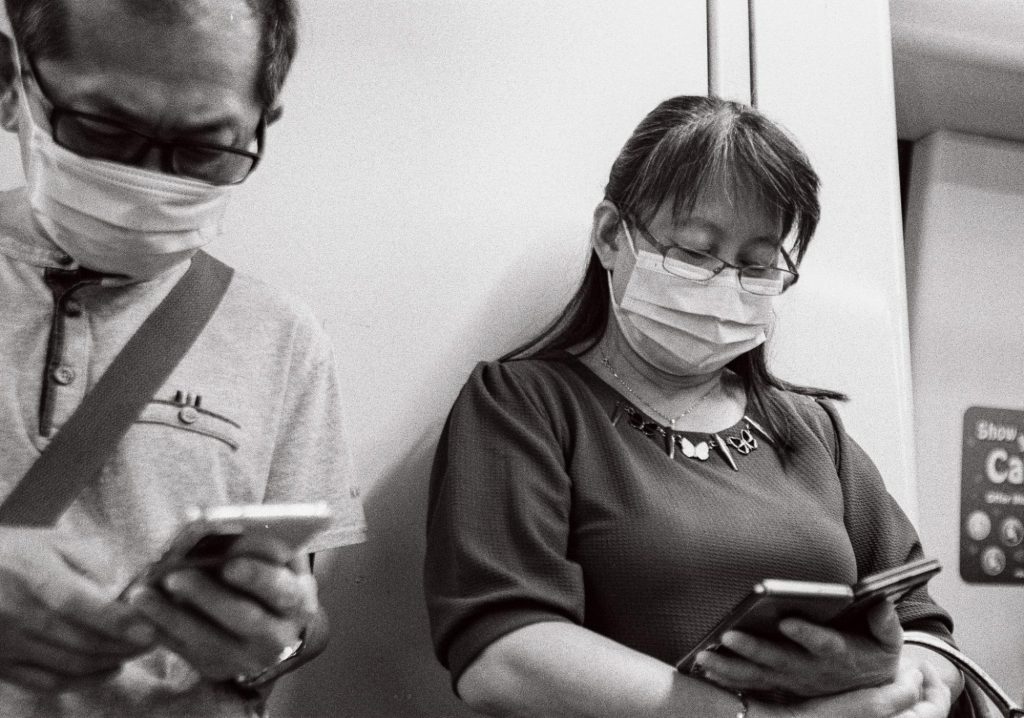

Nothing has made this, or how crippling the lack of digital access can be, clearer than the Covid-19 pandemic.

At the launch of the second edition of the Minimum Income Standards (MIS) study last weekend, Associate Professor Teo You Yenn, one of the study’s authors, discussed how, with HBL, a laptop became a necessity for students to attend their lessons. (Resource lists drawn up for the study include a smartphone, data plan, and laptop as part of families’ ‘must-have’ lists.)

Beyond this, technology has penetrated virtually every aspect of pandemic life, from staying abreast of Covid-19 updates, booking vaccination appointments, working from home, and food and grocery deliveries.

The trouble is that digital privilege—so to speak—is invisible to those of us who have it. Many technological processes are so entrenched as to be second nature, although they involve a number of different parts.

For instance, beyond a functioning device and Internet access, even making a purchase on an online shopping portal involves at least some chain of access, from an email address for account creation and password retrieval, to a mobile phone for two-factor authentication. Frustrate one aspect, and the whole chain collapses.

Devika Kumarasamy, a senior counsellor with Kampong Kampor Community Services, had no shortage of examples when I asked about the challenges her clients face.

Since the pandemic, she, like many of her colleagues in social work, has had to provide ‘emergency tech support’ along with her existing duties.

She works mostly with low-income families and senior citizens, some of whom live alone. While most of her clients in their 40s and below have no issues using technology, the elderly and those with poor English skills tend to struggle.

“Things like online registration and filling out forms are really difficult. With the pandemic, many ministries asked people not to come in in person and do online applications instead, but it’s not always practical. Families might not have a computer, or know how to retrieve documents or have a scanner to scan and upload them,” she explained.

Like Mdm Rani, many of her clients still receive their bills in the post, and make payment at the bank or ATMs in person.

More recently, the shift towards vaccination-differentiated measures has thrown up new difficulties, particularly for elderly folk without smartphones. Devika and her colleagues have been telling their clients to bring a physical copy of their vaccination documents everywhere, just in case their tokens or the Tracetogether scanners don’t work.

“If the government made vaccination cards for them, that would help them access places more easily,” she observed.

“Things you and I take for granted, they are unable to do.”

Attitudes towards digital adoption

This became apparent, when, in the next breath, I referred to email as ‘basic’. Devika leapt to correct me.

“Email is only basic to people like you and I!” she protested. “Most of my clients might have Whatsapp, but I’ve never heard of an elderly client with email. I would be amazed if they did. If you ask some of my clients in their 60s and 70s who work as cleaners, they’ll just look at you like ‘why would I need email?’”

Here lies one of the paradoxes of the digital divide: those most at risk, or significantly affected by it, often struggle to articulate this lack.

While they might recognise the inconvenience of queuing for two hours at the bank in person, or being unable to send and receive messages instantaneously, many struggle to advocate for what they don’t understand or don’t know.

To some extent, this is compounded by scarcity: when money is tight, it’s usually used to buy food and pay bills before anything else.

Devika gave the example of Mr and Mrs Suppiah, an elderly couple she works with. They live alone, don’t have WiFi at home, and only know how to use a landline. In addition, they only speak Tamil, which prevents them from attending most digital literacy classes.

Although schemes like IMDA’s Home Access Programme provide subsidised mobile phones and Internet plans, the pair remain reluctant to get a smartphone or learn how to use one. “I don’t think they see it as a need at this time, but as a want, and they don’t really want to spend that kind of money,” she admitted.

Nonetheless, Covid-19 has driven home the precariousness of their situation. Were either of them to contract the disease, they wouldn’t even be able to Google what to do.

Attitudes towards technology differ greatly amongst the less digitally well-off. The elderly, in particular, tend to be fearful, reluctant, or anxious, while others, like Mdm Rani, are eager to learn but less confident in their ability to pick things up.

“Sometimes I feel bad asking my children for help, like I’m disturbing them. My daughter says mummy, I taught you already, you must learn how to do it yourself, but I cannot remember. It’s frustrating, but I do want to learn,” she says.

Devika’s own experiences have made it easier to understand where her clients are coming from.

“I’ll be frank with you,” she continued. “I just turned 50, I’m reasonably well-educated, and even I feel nervous about certain things to do with tech. I’m always worried about getting scammed or losing my phone. I don’t even use PayNow because I’m so worried about getting hacked.”

“I mean, even people who are well-educated have to be wary about scams and digital security. So just imagine … it can be a world that’s so unfamiliar for people who aren’t as fluent with tech to navigate, let alone without support.”

Narrowing the digital divide: recommendations and principles

At present, digital assistance schemes are split between the state and charity sector, and mostly address the issue of resource provision: ensuring everyone who has a device needs one, or that digital services are accessible and affordable.

The NEU PC Plus Programme and Home Access Programme (HAP), for example, offer government subsidies for computer and Internet access.

To some extent, implementation was turbo-charged by the pandemic: following the Covid-19 crisis in migrant dorms last April, the government announced that dorms would be kitted out with WiFi, and a scheme to provide all secondary school students with personal learning devices was brought forward seven years to 2021.

Alongside these, mutual aid schemes, charities, and NGOs like Engineering Good, or Beyond Social Services’ Kebun Baru WiFi project, have attempted to fill the gaps. Nonetheless, bridging the digital divide will take several concerted steps.

One, as the universal digital access paper argues, is the adoption of standards: recognising digital access as a public utility, and aiming for access to devices on a one-to-one basis.

In this vein, its authors call for the personal learning device scheme to be extended to primary school students, and for the HAP to be assessed on an individual rather than household basis, amongst other measures.

Second is an empathetic, user-focused understanding of the challenges faced by those who still struggle with digital access. Last, and linked to this, is ensuring that ideas are followed by execution—devoting a sustained flow of resources towards improving digital access.

“While recognising Singapore’s commitment and strong efforts in digital inclusion thus far, the gaps spotlighted by Covid-19 have taught us that reaching the most digitally vulnerable takes more than making programmes available,” state the authors. “It also requires social and business knowledge on top of technical knowledge.”

They recommend a more collaborative approach to improving digital access, including drawing on the finances and power of Big Tech.

Meanwhile, the expertise of community workers, for example, is an invaluable resource, particularly in highlighting areas where efforts to encourage digitalisation have fallen short or created problems of their own.

Devika brought up how many elderly clients, especially those without mobile phones, found it even more difficult to use Singpass-related functions after the physical OneKey token was discontinued.

“I personally thought that was a mistake,” she reflected. The token was gradually phased out by April this year in favour of the Singpass mobile app.

“Many of them forget their login details. If they don’t have a phone, like Mr Suppiah, they have to go to the CC to re-activate their account, or they can’t access functions like an OTP,” she said.

Why digitalisation still needs the human touch

The other key area of need—and, arguably, the harder one to tackle—is digital literacy.

The universal digital access paper notes that digital literacy “has implications for access as well as one’s ability to sustain the usage of devices over time in a productive and meaningful manner.” In particular, literacy requires sustained, consistent engagement.

“Literacy in anything cannot be achieved by a one-time session; it requires continued use and practice, and this in turn requires some level of confidence for the individual to keep using the new technology.”

Devika learnt this the hard way: she and her colleagues got a second-hand phone for the Suppiahs and installed WhatsApp on it, but the couple couldn’t figure out how to work the app.

“The day after, I got so many calls from Mrs Suppiah because she was trying to call her daughter, but couldn’t get through or the line hanged or she didn’t know what to press. We realised there’s no use installing apps unless someone can guide them in person, until they’re familiar enough to do it themselves.”

Thus far, Mdm Rani has gotten by with a combination of rote learning for simple apps, asking her children for help, and, when all else fails, relying on the kindness and patience of strangers.

For the moment, her family’s needs are covered—somewhat. Her children’s laptops were provided by assistance schemes, and will not need to be returned even after they finish school. Nonetheless, the devices are starting to age and will need to be replaced. As a housewife, and with her husband currently out of work, it would be impossible for them to afford new ones without help.

We chat for a bit about Zoom fatigue and how much nicer it would have been to meet in person. Mdm Rani tells me her goal is to be able to better support her community; as an avid—and excellent—cook, she would love to start a home-based business.

She agrees when Felicia and I suggest she would probably need a laptop for that, not to mention getting more comfortable with technology than she currently is.

“I need to learn,” she says, not for the first time in our hour-long chat. “Sometimes I feel very nervous, wondering what people think of me when I’m always asking them for help.”

“So far, whenever I have problems, my friends and social workers say it’s okay and they can help. But what happens if they’re not around?”