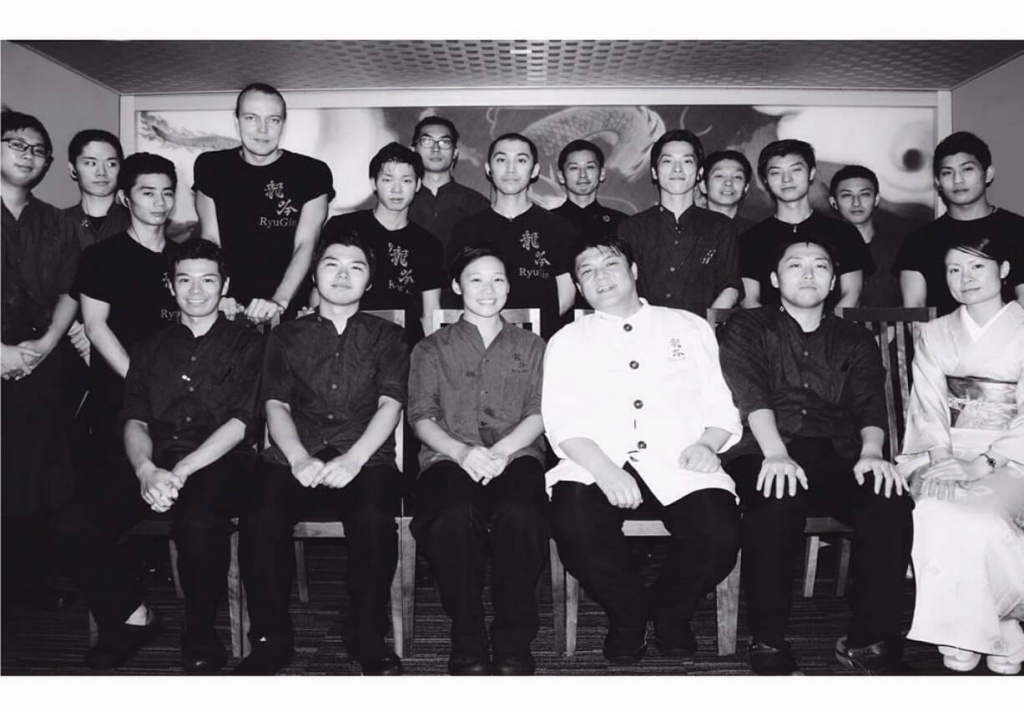

Images courtesy of Ethel Hoon.

Immigration has become a hot topic in the past year. Thus far, the discussion has mainly been centred around foreigners who chose to come to Singapore, but what about the other side of the picture? In ‘Singaporeans Abroad’, we share with you the stories of locals who—thanks to living in a globalised world—have found success in different corners of the globe, whether financially, romantically, or for the pure joy of adventure.

Recently, we’ve heard from Wei Hui, who works with refugees in Syria, and Gary, who was arrested while backpacking in Xinjiang.

Now, we bring you Ethel Hoon. After studying at Le Cordon Bleu and cutting her teeth in some of the world’s best restaurants—most prominently Fäviken Magasinet, a two-Michelin starred restaurant in Sweden which was featured in Chef’s Table—she now runs a restaurant in an Austrian ski town with her husband. Here, she reflects on her journey across the world’s kitchens, the importance of sustainability, and how moving abroad changed her relationship to food—including the food she grew up with back home.

I knew I wanted to cook from a very young age. I have a very clear memory of being 7 or 8 and being asked what I wanted to be when I grew up, and saying that I wanted to be a chef. I love eating—maybe more than cooking!— and when I was growing up, family gatherings always revolved around food. For me, food has always been something joyous; something which brings people together.

After JC, I knew I eventually wanted to be a cook, and while my family was very supportive, they weren’t sure if I really knew what I was getting into or whether I just had this romanticised idea of being a chef.

My dad also made it clear that I should get my degree before going into anything else. So I studied hotel management, and after graduating, I went to cooking school at Le Cordon Bleu for a year.

I didn’t have a clear idea of what sort of chef I wanted to be at first, but I wanted to learn French cooking. At the time, I thought it was the most technical style of cooking; a lot of modern European fine-dining places are grounded in it, and my dream was to work my way up the very traditional, brigade-style system these restaurants use.

I was very lucky to have that opportunity and to be in Paris, where I was exposed to the city’s food culture and markets alongside what I was learning in school.

After graduating, I interned for three months at an old-school French fine-dining restaurant, and when my visa expired, I came back to Singapore and worked as a commis chef at Les Amis for a year.

It was incredibly intense—we worked five or six days a week, which I don’t think my body could physically take now!—but I was starting out and eager to learn, so I didn’t mind the hours. I also had great colleagues and a mentor in Chef Sebastian, the head chef.

All the same, after moving back to Singapore, I’d begun to feel this strange sense of disconnect with the ingredients I was cooking with and where our food comes from.

In Singapore, everything is imported. All our produce comes in plastic bags, and there’s this lack of consciousness over where it was grown. If something isn’t in season in Europe, you can get it from Australia and vice versa. This is great for us as consumers, but having spent some time in Europe, I missed the hyperseasonality and the variety of produce there, like when I’d go to the markets in Paris and see these beautiful artichokes, or a fresh delivery of birds with the feathers still on.

Here, I was like: how was this pork raised? Where did these tomatoes come from?

I didn’t think I’d leave forever, but I wanted to see something new, and Chef Sebastian was very supportive. I’d saved up some money, and just around the time I left Les Amis, I was accepted for a two-month stage, or culinary internship, at Fäviken.

I did a stint there, followed by two more stages in Hong Kong and Tokyo, and returned to Fäviken in 2015 when an opportunity came up.

Fäviken was located on a hunting estate in rural Sweden. The land is privately owned by a Swedish family, and the restaurant maintained very close ties with local farmers and suppliers, which gave us a lot of insight into how and where our food was grown.

The restaurant has since closed, but being there was amazing. Any chef will tell you that working with good produce gives you this deep, inexplicable joy, and being able to work with such a skilled team, with ingredients you’d never find in our side of the world, in ways which I wasn’t accustomed to, reignited my love for cooking in ways I hadn’t expected.

Collecting from the land when it’s bountiful and preserving what you find for the less abundant months is a very old way of living, and doing it feels almost like going back in time. For six months, it’s winter, when it’s cold and stark and nothing much grows; then you have beautiful long days in spring and summer, when the land colours and transforms.

Collecting enough for the season was a community effort. In the summer, we’d go out and forage for mushrooms and berries, like lingonberries and cloudberries, and preserve these for the winter months. The neighbour might pick some while walking her dog and sell them to the restaurant. Game like wild birds came from the hunting grounds on the estate itself, shot by a hunter or the family.

I was in charge of the pastry and snacks section in the kitchen, and one of my favourite items on the menu was this small snack we’d serve at the end: a sunflower-seed tart with birch syrup and shavings of dried reindeer meat, which reminded me of bak kwa.

Birch syrup is a bit like maple syrup. You tap sap from the birch tree and reduce it till it thickens, which gives it the most incredible complexity and acidity, like a nicely aged Balsamico—caramelized notes with a bit of bite and a toasty, nutty, flavour. The sap came from this guy we called Mr. Duck, because he lived near the restaurant and raised the most beautiful ducks.

It was during this time that my relationship to food became much more conscious. I realised that where and how something is produced is just as important as how it’s prepared in the kitchen. Magnus ([Nilsson], Fäviken’s head chef) always used to say that you can never make something good out of something bad, and ever since, I’ve found it so important to know how food is grown, sourced, and transported, and to work with people who grow it sustainably. Industrialised farming doesn’t just produce poor-quality food; it’s bad for the environment and bad for us as consumers.

Before Fäviken, I didn’t care much about where my food came from as long as it tasted good in the end. Working there showed me how interconnected things really are.

It was also at Fäviken that I met Jakob, my husband, and started Hoon’s Chinese, a pop-up concept serving Singaporean Chinese food. Magnus had a bit of extra space in town, and he asked if I would be keen to do a Chinese pop-up for two months in the summer, which was how it all started.

It was the first time I’d cooked Singaporean Chinese food in a commercial setting, and when Magnus first proposed it I was hesitant. I’m Singaporean, but I knew so little about how our food is made, and in a strange way, I felt like I wasn’t cut out to make food from my own culture.

The first time I’d made chilli crab had been when I made it for a staff meal at the end of my first internship at Fäviken. Basically, I felt like a fraud.

But I did some research, and it opened up a whole new world to me in terms of our local cooking techniques. Stuff like wok hei—imparting complex flavour through a time-seasoned vessel in a fairly simple way—isn’t something you see in Western cooking. Even steaming, where a just touch of heat brings out beautiful colour and texture, isn’t that common.

It’s funny that it took someone from another country to push me to make food from my own culture, but I’m really grateful to Magnus for giving me that nudge. It opened me to things I’d had on my doorstep but never looked into, and which are just as valuable and interesting as the French fine-dining I’d originally aspired towards.

It’s not too late to discover it now, but I wish I’d had more interest in Singaporean cuisine from the get-go. It would have expanded my understanding of food a lot more if I’d recognised this from the beginning.

Jakob and I left Sweden in 2017 and spent a year in Berlin before coming to Lech, a small village in the Austrian Alps, where we live now and opened Restaurant Klösterle in late 2019.

The restaurant operates in a fairly casual setting, which is quite a step away from our backgrounds in fine dining. It’s very small—30 to 35 guests maximum—and everything is done to share. Dishes are passed around, kind of like how you’d eat at home, which was our vision for the restaurant. We want you to feel like you’re guests dining in our home, and create a convivial experience that isn’t solely about the food. It’s how we both like to eat.

Running a restaurant has been a very steep learning curve for us, but getting to make your own decisions, rather than having someone make them for you, makes you very conscious about your choices.

For instance, we’ve been trying to incorporate more vegetables into our menu. They’re so often overlooked in this part of Europe, and we feel that if we do eat meat, it should come from places that do right by the animals and right by the land. Sustainability, transparency, and respect for nature are all very important to us; we want our guests to understand the full chain behind what is on their plates.

At the end of the day, I don’t think cooking for the love of food, versus cooking because you want to make people happy, are distinct. The more I’ve done, the more I’ve realised how much I enjoy cooking for others, and getting to meet so many interesting farmers, producers, and guests. I love being in the kitchen and the technicality of preparing a dish, but it’s the idea of what food can do and how it brings people together which resonates most.

Do you know any Singaporeans with interesting experiences abroad? Let us know at community@ricemedia.co. And if you haven’t already, follow RICE on Instagram, Spotify, Facebook, and Telegram.