Top image: Workers’ Party / Facebook

Raeesah Khan should be fined S$35,000, and Workers’ Party leaders lied to the Committee of Privileges.

The above is tl;dr of what you would already have known from the mainstream media when you chanced upon this article.

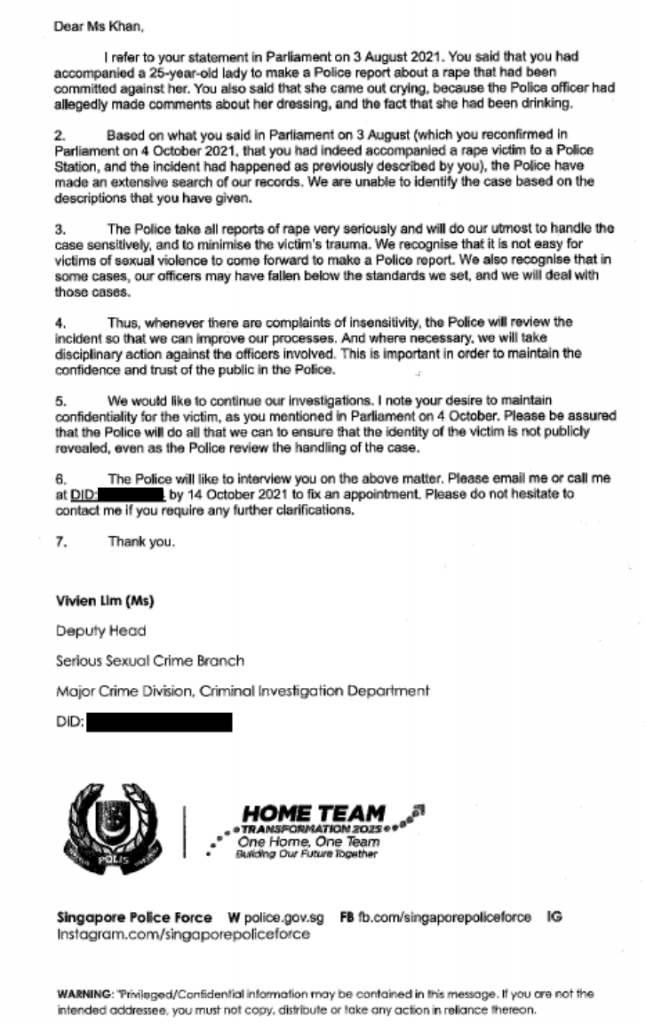

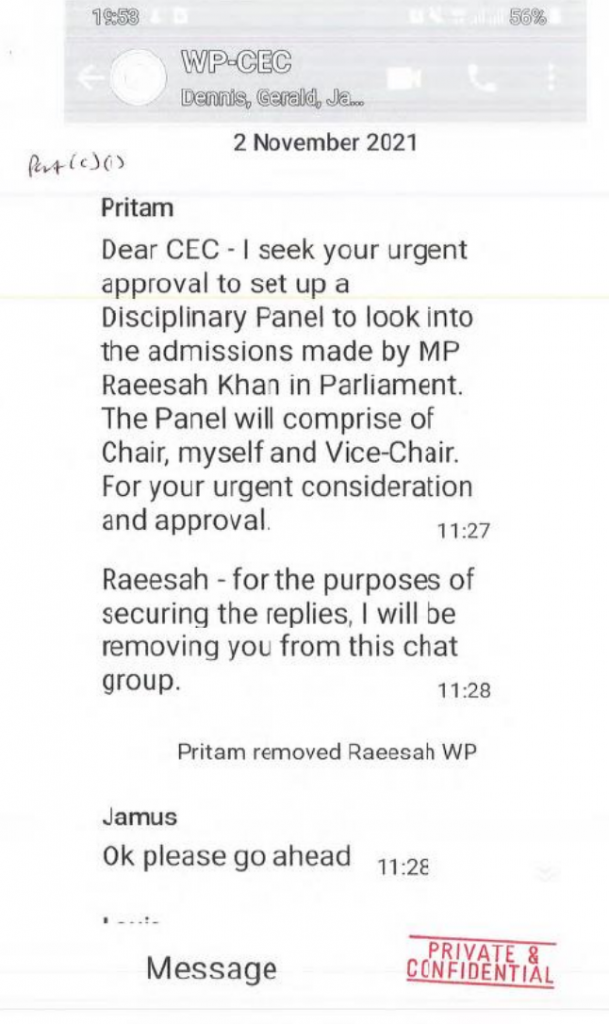

Yesterday (Feb 10), the committee submitted a report of its findings and recommendations to Parliament. MPs will debate on this next week before the annual Budget season kicks off on Feb 18. In a statement, the WP said its leaders—Mr Pritam Singh, Ms Sylvia Lim, and Mr Faisal Manap—will speak on the report in Parliament.

Chaired by Speaker Tan Chuan-Jin, the eight-member parliamentary committee was formed to investigate a complaint against WP MP Raeesah Khan for lying in the House. Ms Khan resigned from the party and her Sengkang GRC seat on Nov 30, 2021.

But there is more to unearth from the 1,181 pages report.

The differences in punishment: WP leaders vs Khan

In its report, the committee proposed Khan be fined S$35,000—S$25,000 for telling the first lie on Aug 3 and S$10,000 for repeating it on Oct 4—and Messrs Singh and Faisal be referred to the Public Prosecutor for further investigation.

The proposal to fine Ms Khan isn’t unexpected. After all, she had already resigned as an MP and the committee had fewer options.

She couldn’t be suspended or expelled from the House (both viable options according to the law) because she was no longer an MP when committee proceedings started. Other options would be to issue her an official reprimand or put her in jail, both of which are technically possible but questions might be raised on whether these actions are proportionate to the severity of the mistake committed by Ms Khan.

Committee’s reason on why WP leaders should be dealt with by Public Prosecutor

Ironically, things are more straightforward for the original offender (i.e. Raeesah Khan) than the WP leaders, Messrs Singh and Faisal. The suggestion by the committee to refer the two leaders to court might create more significant political implications for the party, as this issue gets dragged on further with no proper closure.

According to the report, if it’s true that the WP leaders guided Ms Khan to repeat the lie, then there should be a separate investigation because the misconduct would be beyond the scope of the current committee, which only looked at the complaint based on Ms Khan’s untruth.

The report also indicated a reluctance to form another Committee of Privileges, stating that “it is unlikely that another [committee] will make much progress, in itself, in uncovering more evidence.”

The rationale for referring the WP leaders to court can be derived from what the committee has laid out in the report:

Given the seriousness of the matter, it appears to us best, in this case, that it be dealt with through a trial process, rather than by Parliament alone. In that way:

(a) the Public Prosecutor will have the opportunity to consider all the evidence afresh, and also consider any evidence that this Committee may not have considered, (for example, if such evidence has not been presented to this Committee, but emerges subsequently) before deciding whether criminal charges should be brought against Mr Singh;

(b) Mr Singh will have the opportunity to defend and vindicate himself, with legal counsel, if criminal charges are brought; and

(c) a court can look at the matter afresh, and consider any further evidence that may emerge, and decide whether any charge(s) have been proven, or not proven, beyond reasonable doubt.

Based on the explanation given, there’s an emphasis on considering new evidence that may emerge or may not have been thought of previously by the committee. This could imply that the committee, which started its work as of late-Nov 2021, didn’t have enough time or capacity to do a more thorough fact-finding exercise.

Perhaps this was due to Mr Faisal’s refusal to answer specific questions by the committee. Referring the matter to a public prosecutor may compel him to reveal evidence that should have been presented earlier at the hearings.

Still, one can’t help but observe that the committee, dominated by People’s Action Party MPs, may have made this move out of tactical reasons. Given that the WP leaders are still seating MPs, any sanctions implemented by the committee may create bad political optics for the ruling party. The courts would be an impartial body to make the final judgment.

At the same time, the committee might not want to let the WP leaders off too easily if they indeed had committed wrongdoings deserving of a higher penalty.

The PAP may think that by referring the matter to the courts, it can absolve itself from this saga and not sacrifice unnecessary political points. This, on the back of criticisms that it was using the platform of a committee as a political vendetta to put the WP leaders to task.

The reason behind Sylvia Lim’s lower penalty

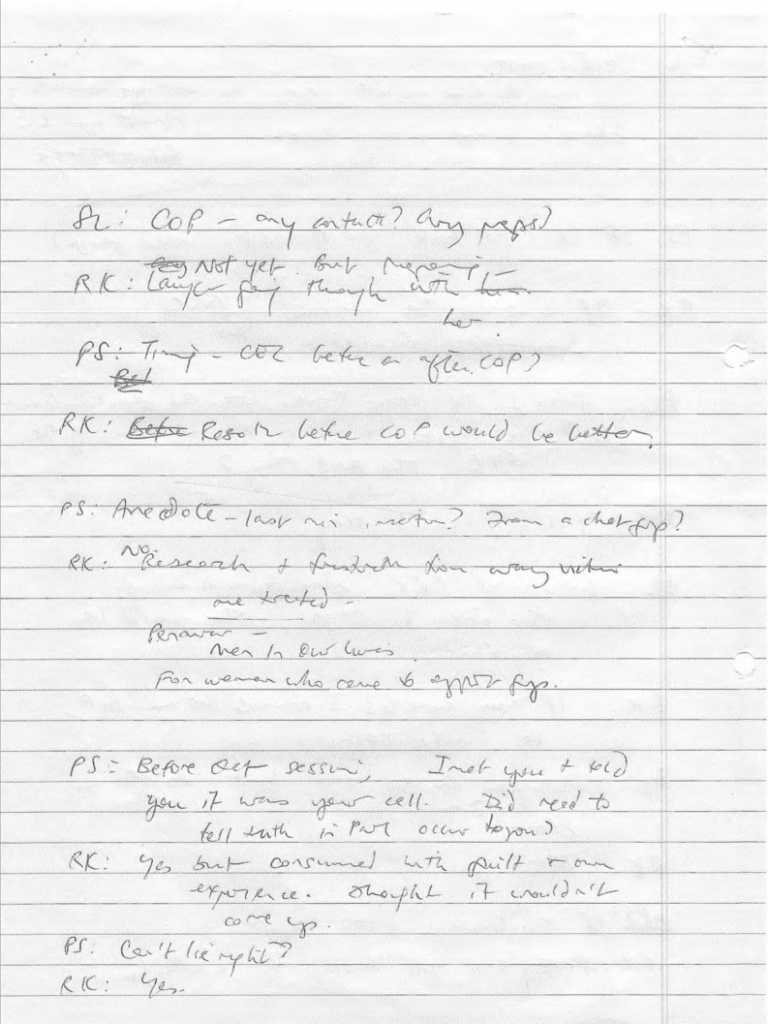

The report suggested a lighter sanction for the WP chairperson because she willingly produced evidence to the committee—her handwritten notes from the party’s internal disciplinary panel—which it was previously unaware of. This is what the committee members said through the report:

Ms Lim, a lawyer and chairman of the WP, would have appreciated the effect of such evidence. It would be, and was, extremely damaging to the testimony given by Mr Singh—it directly contradicted Mr Singh’s evidence that he did not give Ms Khan a choice. Ms Lim was clear in her testimony that a choice to tell the truth cannot be given to the WP MPs (an obvious point). That was also directly contrary to what Mr Singh had done, and Ms Lim recognised that.

What does this mean? In the eyes of the committee, because Ms Lim voluntarily produced documents that didn’t shed a good light on her party’s secretary-general, they proposed that if an action has to be taken against her, this voluntary move should be taken into account.

Perhaps Ms Lim didn’t have a choice either. As the most seasoned parliamentarian among the three leaders—she has been in the House since 2006—and a trained lawyer, she might have known well enough to be upfront with evidence than to face graver repercussions if exposed later, which wasn’t entirely impossible if a party insider caught wind of the existence of the document and decided to whistleblow.

With such a conclusion by the committee, questions remain with regards to the dynamics between Mr Singh and Ms Lim and her future in the party, especially with the central executive committee election later this year.

Raeesah Khan wanted to withdraw her allegations, but …

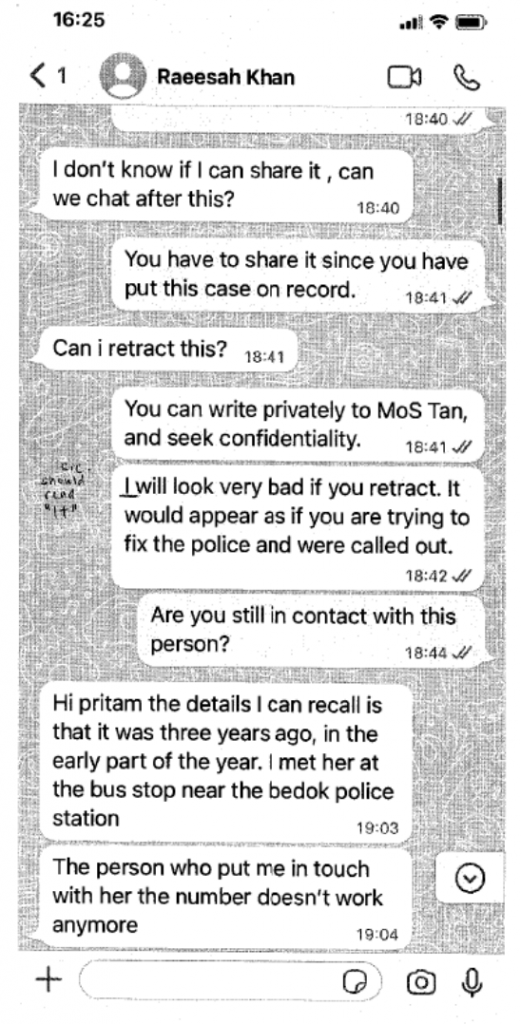

Suppose one has the stamina to read till page 185 of the report, they will see that on Aug 3 last year, after Ms Khan told her first lie in Parliament, Mr Singh whatsapped her saying that he “had a feeling this would happen”, referring to the questioning by the government after she made the allegation on the police.

Subsequently, Ms Khan asked Mr Singh if she could retract the allegation. However, what could be seen as damning was the reply after that, where Mr Singh said he would “look very bad” because it would seem as if they were trying to fix the police and were called out (NB: in the Whatsapp screenshot below, a handwritten portion underlines the first ‘I’ in the message with a remark that reads ‘sic should read “It”’).

By these messages alone, it appears that Ms Khan had intended to withdraw her words and move on, knowing she couldn’t stand by what she said. But the subtle pressure by Mr Singh might have made her change her mind.

As an inexperienced politician, Ms Khan might be confused as to her next course of action and eventually chose not to withdraw her words if she perceived that move as a poor reflection of her party’s leader.

Dennis Tan’s interventions in the report’s findings

Towards the end of the report, there were minutes of the committee’s meetings attached. Some of these documents had been released last year in a series of special reports, but others were new, such as the final two meetings in February.

From the minutes, the committee was deliberating on the wording of the final report in the February meetings. A total of six amendments were raised by the only WP MP in the committee, Mr Dennis Tan of Hougang constituency, and approved by other members.

Can such a move be seen as a greater latitude on the part of the PAP MPs on the panel, where they take in feasible suggestions by the Opposition?

It is also worth noting from the recommendations that Mr Tan had originally suggested a higher penalty for Ms Khan than the rest of the committee. While everyone else proposed and finally decided on a quantum of S$10,000 for the second untruth uttered, Mr Tan’s view was that she should be fined S$15,000 instead.

The report only stated that Mr Tan rejected the basis behind the quantum of the second penalty, which is that Ms Khan was influenced by WP leaders to carry on with the lie, among other considerations. However, the report didn’t mention why he brought up a figure higher than what the PAP MPs suggested.

Gems in the appendices

There aren’t many new revelations from the appendices, since they are just a collection of the evidence that was already presented at the committee hearings last December.

Still, it feels different looking at the raw documentation first-hand instead of reading a sanitised version in the media.

Most of the documentation is emails, transcripts, and screenshots of conversations between Ms Khan and various individuals, be it with her party leaders or her aides. There were also Whatsapp conversations attached in the report between Mr Singh and Raeesah Khan’s father, Mr Farid Khan.

The handwritten notes jotted by Ms Lim, as mentioned earlier, is also part of the appendices. You can read them on pages 158 to 219 of the report.

Some insights can be gleaned from these conversations, such as the no-nonsense leadership style and character of Mr Singh, through a parsing of the language and tone he used in the messages and emails.

Mr Faisal Manap, for example, appeared to be Ms Khan’s confidant and was gentler with her, telling her to “stay strong sis” (sic) and “Allah will always be with those who are in need of His assistance. Do regularly turn to Him.”

The high level of trust and friendship between Khan and her assistants, Loh Pei Ying and Yudhishthra Nathan, can also be seen from the candidness and informality in the messages.

Questions remain on the report

It’s still unclear why the committee decided to release its report yesterday with a debate next week, a few days before Finance Minister Lawrence Wong is due to deliver his Budget statement.

After all, the release and debate on this report had been widely expected to happen earlier in January when the parliamentary calendar was emptier. It was less likely for the debate to be this month as MPs are busy preparing their Budget speeches.

There are two possible reasons for the timing. The first is that the ruling party wants the news cycle over this saga to be overtaken by developments of the Budget debate.

After all, Parliament is highly likely to give the green light to the findings and recommendations of sanctions to the relevant WP MPs, and it might not look favourably on the ruling party. So the less attention on this, the better—a mantra similarly applicable to the WP since this saga is about the wrongdoing of its former MP.

The report’s release can also be seen as a manoeuvre to distract Singaporeans from news of a looming Goods and Services Tax hike. Nobody likes an announcement of a tax increase, as necessary as it may be, and news from the Committee of Privileges is helpful to shift negative attention away.

But ultimately, how each party, PAP or WP, is perceived depends on Singaporeans. So even if the issue is eventually followed up in the legal courts, what matters is the court of public opinion when the next general election, due in November 2025, is held.

Whether WP will be forgiven or seen as a dishonest party, or the PAP seen as a bully or a party on the moral high ground—is really up to the voters.