Top Image: Théo Dorp / Unsplash

Fiona* was only 23 years old when she owed $44,000 to a mega furniture retailer.

“I had just started working. Landing with this huge debt as I was starting out on my own was just a lot for me,” she admits.

At that time in 2010, she had just moved into a new 3-room flat in Hougang with her sister and mother, and the house needed new furniture. She made a trip down to Courts with her mother to get the necessities.

The total damage was only worth $20,000. But because they opted to pay for the items through Courts’ in-house instalment plan, she ended up having to pay $44,000—more than double her original bill.

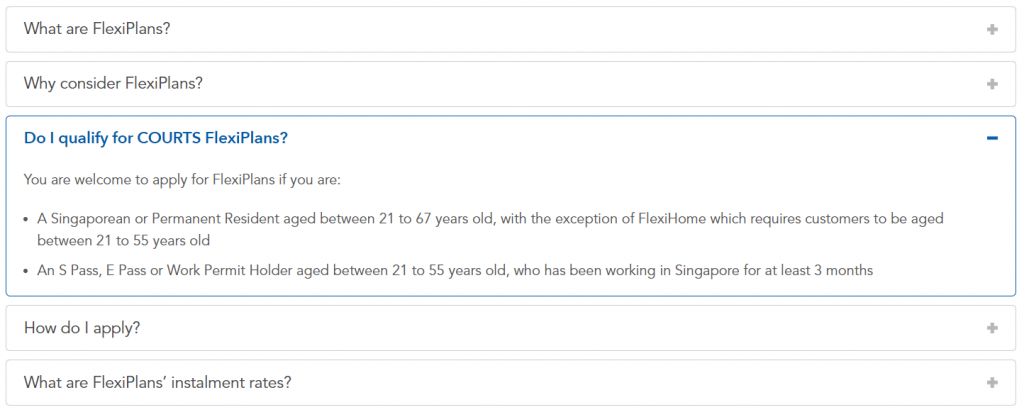

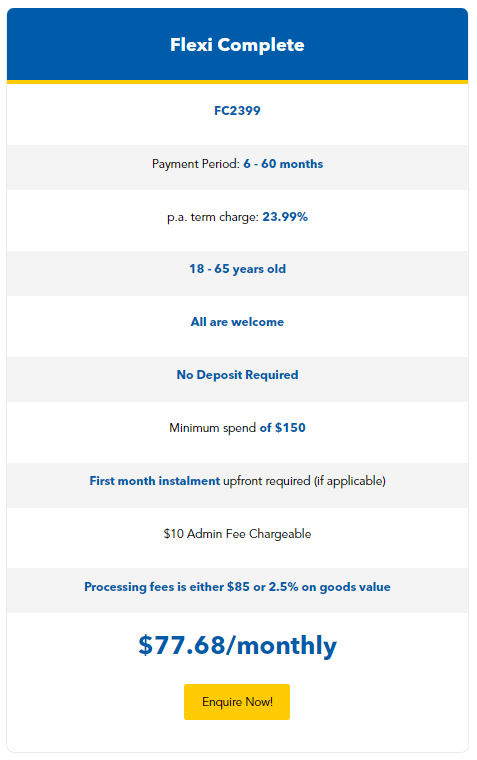

FlexiPlans is Courts’ in-house instalment plan. The payment period varies with each plan but usually has a minimum of six months and extends for as long as five years. Its interest rates start at 11.99 percent and can go up as high as 33.99 percent per annum.

Interest rates don’t deter those who are in need of urgent furnishings or those who aren’t so financially savvy. Plus, the plans’ low monthly payments are extremely attractive because they don’t have to pay everything upfront.

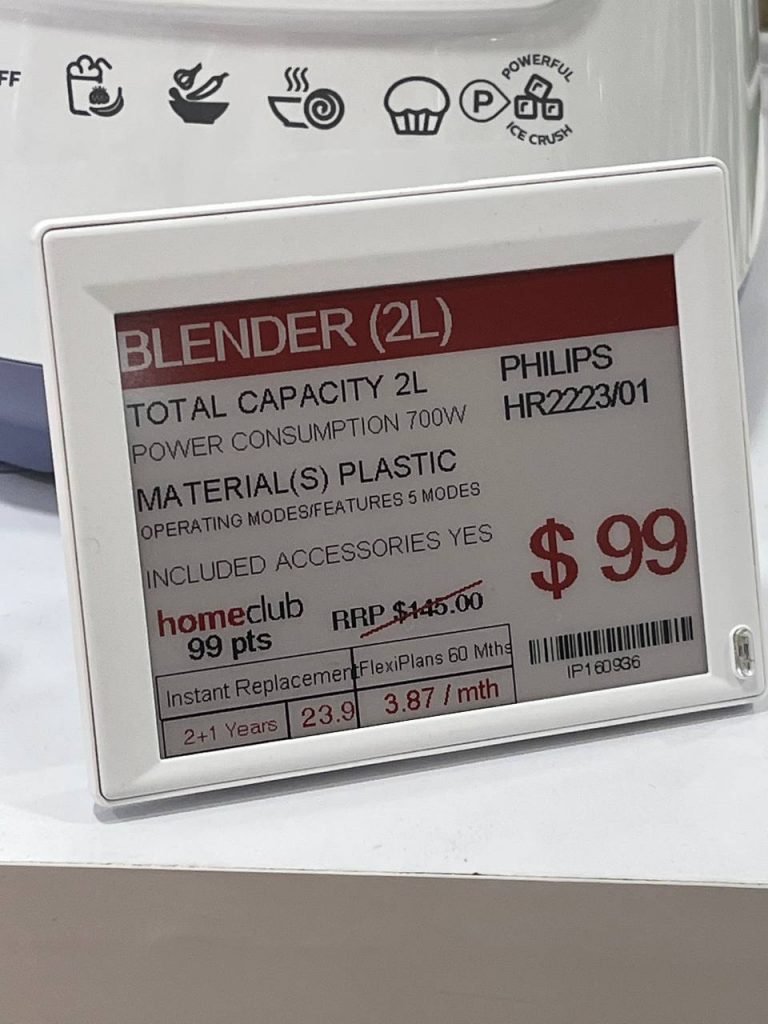

For a blender that costs $99, the monthly payment can go as low as $3.87 if you spread it across 60 months. But why should anyone end up paying $232.20 ($3.87 x 60) in total for a $99 blender?

Due to pressure or lack of clarity, customers sign up. And they end up having to pay a hefty price for it in the long term.

Signed, Sealed, Delivered

It isn’t just the low monthly payment that makes the Courts’ FlexiPlans appealing to lower-income families. Fiona’s mother was also won over by the promise of an instalment plan that didn’t require a credit card or a good credit score. She was convinced it would be fuss-free, though her daughter thought differently.

“I was quite scared because it’s an instalment plan—there’s always some catch. I am the kind of person who will read the fine print, so I was very wary about it. But my mum kept pushing for it,” the now 35-year-old editor says.

At 23, Fiona was a fresh university graduate who just started a new job. But having only just returned to Singapore after studying overseas for eight years, she was under tremendous pressure from her mother to “pull her weight” around the house.

While her starting pay wasn’t much, she was still earning more than her mother and sister. She was expected to bear the brunt of the household’s financial burden for the new furniture.

So when it was time to pay, her mother put her name down on the forms with no hesitation.

“They did all the signing in the store. So you can imagine that I can’t sit down to calculate on my own and consider my decision. Everything was already there for me to sign.”

“I didn’t know better, so I just submitted everything.”

The family received their furniture that very weekend. But Fiona remained uneasy.

“It kept me up a lot the next few nights. Because when I calculated the interest and everything else later, the total amount came up to almost $44,000.”

Fiona later found out that while her mother was worried about her own credit score upon taking on the debt, she was under the impression that putting down the name of another working member of the household would be a solution.

“It’s a lot to carry for whoever’s name is on the documents,” Fiona attests.

It’s the consumer’s responsibility to weigh their options before making any big purchase. But there could be more education on the expected outcomes of such instalment plans with heavy interest rates.

Throughout the process of applying for the FlexiPlans, Fiona recalls feeling unsure and hesitant about what she was signing up for. While she was aware of the interest rates at the time of purchase, she believes the final price and consequences of late payment could have been presented more explicitly.

Though she was well aware of her financial situation, Fiona took comfort in knowing that the FlexiPlans only charged additional interest if they were more than three months behind in payment. Late payment fees would then be applied to overdue payments.

But missing payments wasn’t as harmless as she thought. Fiona found out the hard way.

Letters, Calls, and People at the Door

“Because I was paying for other household bills, I wasn’t doing so well financially. I would miss a payment or two. And there would be warning letters, people knocking at the door, and calls,” she recounts.

“It was quite scary.”

Despite the original payment period set at three years, it took Fiona six years to finish paying off her debt because of the additional fines.

She continued to feel the effects of the tremendous debt she took on even after paying it off. The debt affected her credit score, which caused some hiccups when she wanted to sign up for an insurance plan.

She had to make sacrifices and cut back on her spending in other aspects of her life, such as her wedding, because of the giant dent the debt made in her bank account.

It took a financial and emotional toll on her as someone in her early 20s. While the monthly payments started off at $300 in the first few months, they gradually went up to $600 at one point—half her paycheck when she started as an intern.

“I really had no money then, so it was a lot of suffering. Everything just felt so tight, and I had no help at all. I felt like I wasn’t allowed to ask my sister to help me, and so I had to pay everything off on my own.”

$5K For a Super Single Mattress

Azfar*, a 39-year-old who works in the media industry, shares a similar experience with FlexiPlans.

In 2009, he bought a super single mattress from Courts, priced at $1,999. As a 25-year-old who had only started working, the amount was too much to splurge at one time. And Courts was pretty much the only furniture retailer available at a time before e-commerce became mainstream.

He decided to opt for FlexiPlans, which offered an enticing price of only $99 a month.

He didn’t expect to end up paying $4,752 at the end of his four-year payment period—nearly a 238 percent markup of its original price.

It didn’t occur to him that the interest rate would add up to such a significant amount. The only reason he remembers that it was $99 per month was because of how much it was emphasised.

“I would expect them to have shown me the whole piece of paper, which shows me that I’m paying $99 per month, multiplied by this number of months, which equals this final amount. I want that. But that wasn’t given to me.”

If he knew what the final amount would add up to be, he might have been more hesitant about opting for the plan. But at the time, it didn’t seem like a big deal for a necessary purchase.

“It was just $99 per month. At that point, it wasn’t important that I was paying more than double at the end of the day. The most important thing is that I got a mattress.”

Azfar recalls being convinced by the ads he saw back then, which seemed to promise a quick, easy way to purchase essential furnishings.

“But when something feels too good to be true, especially when it comes to money, it probably is.”

Sales Strategies

To check if FlexiPlans are still as actively being promoted by sales representatives in Courts as they were a decade ago, we visited three Courts branches to ask some questions as customers.

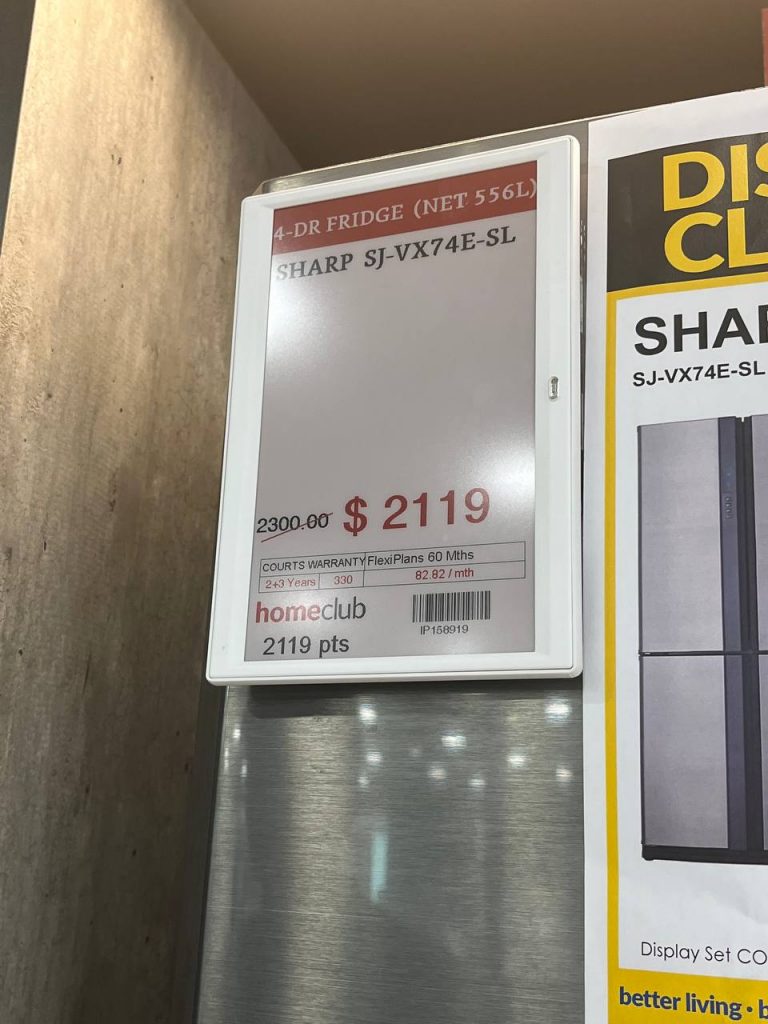

It’s not hard to spot the FlexiPlans promotions. They’re found on most price tags across the store—an attractively low monthly payment plan under the product’s intimidating original price.

For example, the original price of this Sharp fridge is $2,119. As stated on the price tag, if you opt for FlexiPlans where you can pay $82.82 for 60 months, you’ll end up paying $4,969.20. Compared to the original price, this is a 135 percent markup. Opt for a shorter duration, and you’ll pay less.

Across all three branches, I inquired about big purchases—a washing machine, for example—and mentioned that I was on a budget.

Even when I stressed my tight budget, the salesperson at Woodlands simply suggested that I pick a washing machine with a lighter load than the one I asked for. At Choa Chu Kang, I got an apologetic smile that the appliance she showed me was already the cheapest one. The salesperson at Funan introduced me to the 0 percent interest credit card instalment plans.

There was no suggestion of FlexiPlans until I brought it up.

At Funan, I pointed at the price tag of a desktop monitor, asking what the FlexiPlans prices meant.

“FlexiPlans has interest, while the credit card plans don’t. Usually, FlexiPlans interests are around 24 percent if I’m not mistaken.”

“But I don’t have a credit card,” I said.

“Then you can go for FlexiPlans. But the interest rates are quite high. Some will say that it’s not worth it to get it,” he shared.

At Woodlands, the salesperson explained that it was the Courts’ in-house instalment plan and asked me if I was working. When I told her that I was still studying, she quickly told me that I couldn’t sign up because I didn’t have CPF. She then suggested that if I had an older sibling who was working full-time, they could probably apply instead.

There was no mention of the interest rates; neither did she advocate for it. When asked if she recommends the instalment plan, she simply said that it depends because it wouldn’t be suitable for everyone and is only allowed upon approval.

The salesperson at Choa Chu Kang was surprised when I asked about FlexiPlans. She immediately told me that it had high interest rates.

“Do you have a credit card? If you do, then you can opt for the instalment plan without any interest. If you don’t, then you shouldn’t use this instalment plan.”

I pressed her about the interest rate.

“It’s very high; you’d better not. The interest can go up to 24 percent; it’s not worth it,” she warned.

The hard-selling of FlexiPlans, which may have been prevalent a decade ago, is no longer as prominent in their sales strategy today. Perhaps even the salespeople knew that the instalment plans might just land customers in tears.

In any case, Courts has since created a portal on their website to educate consumers on FlexiPlans. Though there is a calculator to estimate the amount one would need to pay monthly, it’s not laid out clearly how much one would pay in totality via FlexiPlans.

People in need, like Fiona and Azfar, would have appreciated better transparency back when they signed up.

On Fairness

The vice president of the GYC Financial Advisory, William Cai, spoke in CNA’s Talking Point regarding the issue of these instalment plans. According to him, he thought that it was not worth it to spend such a significant amount on interest.

But at the same time, he said that the amount of interest charged by furniture retailers was not unreasonable.

“These types of loans are unsecured, like credit cards… Based on that as a reference, it’s fair,” Mr Cai told CNA. He mentioned that credit card interest rates are usually between 24 to 26 percent.

In addition, the furnitures’ fast depreciation meant that these retailers stood to lose more compared to other businesses.

“The value could go to nearly zero in a short period of time, and the retailers face quite a high risk getting involved in such a business. So I’d say it’s pretty fair,” he explained in his comment to CNA.

It’d be unfair to pin all the blame on Courts as well—shouldn’t consumers bear the responsibility of knowing exactly what they’re signing up for?

In reality, desperate consumers could feel they have no other options. Nor are they always financially literate enough to understand the long-term repercussions.

These high-interest plans don’t discriminate against low-income groups, which can come in handy for necessary big purchases. As Courts told CNA, the furniture retailer does “offer zero percent instalment tie-ups with the major bank credit cards, but recognises that such options typically have a minimum income threshold, which not all consumers can meet”.

Courts also offers Absolute 0%, a separate in-house instalment plan with a 0 percent interest rate. But because of its shorter payment period of two to five months, the monthly payment amount would be higher, making it less accessible to consumers with lower incomes.

In this case, the lower monthly payments are the logical and more attractive option to families or individuals who are living hand to mouth. But they will end up having to spend more than a family well-off enough to pay for their necessary furniture upfront.

Additionally, even the most financially literate or prudent are unable to foresee if anything goes wrong in future. Linda, who declined to use her real name when speaking to CNA, was one such customer.

While she was able to make her monthly payments at the beginning, she began to default when her husband met with an accident and was unable to work for a year, CNA reported.

Her debt accumulated from $3,000 to $30,000.

Affordable Risks

Despite our repeated attempts for clarification, we did not receive a response from Courts.

We still don’t know what the company’s stance is; their current in-store procedures for the FlexiPlans application; or what intentions they have for FlexiPlans.

But even if the FlexiPlans is considered ‘fair’, it tells a cautionary tale for the currently growing culture of ‘buy now, pay later’ (BNPL), which offers an illusion of affordability.

Burned by instalment plans with interest rates, Fiona and Azfar have now turned to BNPL services to help finance hefty purchases.

In recent years, BNPL applications like Atome and Grab Paylater have been growing in popularity in Singapore. Most BNPL services allow consumers to split their payments into monthly instalments and don’t require credit checks.

There is transparency, at least. With 0 percent interest, consumers know upfront they’re not paying anything more than the price advertised.

“I don’t like to drag my debt now. So, if I really need to make a big buy, I’d opt for services that would allow me to split my bill into three payments, like Atome. Because I can pay it off immediately in three months, and there’s no interest accumulating,” Fiona explains.

But it doesn’t mean it’s entirely foolproof. It could be dangerous for younger people who may not be financially savvy or independent.

Fiona recounts a time she went to Sephora and saw a group of younger girls queuing in front of her using Atome to split their payments. After calculations, their bills only came up to $15 a month.

“It sounds good, but that’s so dangerous. I would say it’s a trap—it’s that image of affordability sold,” she says.

“$15 a month may seem like nothing. But then that month, you’ll buy something else under instalment, and the $15 will become $40 a month. Once you start doing that, that’s not going to be your only buy. And that’s the risk.”