In ‘Singaporeans Abroad’, we share with you the stories of locals who—thanks to living in a globalised world—have found success in different corners of the globe, whether financially, romantically, or for the pure joy of adventure.

We’ve recently heard from Mr Ting, a Singaporean stuck in Shanghai’s lockdown, and Charine, a Singaporean who quit her successful career to become a nomadic sommelier.

Now, we bring you Kenneth, the chef who has risen the ranks to become the head chef at Noma, the best restaurant in the world, located in Copenhagen, Denmark.

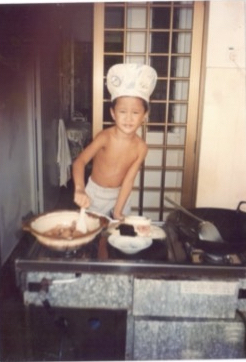

While I was raised like a typical Singaporean, I was more involved in the kitchen than your average local boy. My earliest memories are of me cooking, either standing on the stool helping my mum cut ingredients, or baking croissants from scratch with my dad. It was always my way of bonding with my parents.

While cooking was always a hobby of mine, I actually wanted to pursue a formal education in jazz performance. I was practising music every day, but the prospects and viability of becoming a successful performance artist made me reconsider entirely. I knew I wasn’t going to stack up to my peers in music school, so I decided maybe being a chef was better suited for me.

Since both music and culinary school were unconventional career choices for a Singaporean, I did often feel different from my peers at school. When I was growing up—and probably still now—everyone aimed to be a doctor, lawyer, or at the very least, an engineer. But I was fortunate enough to be born into a family that was very supportive of exploring your interests, passions and hobbies. They never taught us to focus on the money aspects of things.

Many relatives and teachers had always thought my passions were a joke. “You’re just making an excuse because you are lazy,” they would tell me. But I’ve always found it strange how wanting to be a chef is unfathomable in Singapore, a place with so many foodies and such a sizable culinary culture.

I knew I wasn’t the conventional Singaporean and that I wouldn’t be happy with the typical Singaporean life anyway, so I focused on what I loved to do, which was cooking and being surrounded by others passionate about the craft.

The gift that is New York

I eventually decided to go to culinary school in New York. One thing led to another, and I ended up staying for six years, after which I returned to Singapore because of visa issues.

I’d be lying if I said I wanted to come back. New York is exceptional, and something about the energy there is different to Singapore’s. In Singapore, there is an idea of a utopian society where everything is efficient, perfect, and organised. There’s a lack of chaos. People think that chaos is bad and that it is the absence of order, but in a place like New York, that chaos leads to creativity and energy, and for me, it made me hustle on a day to day basis.

I like to describe New York as one of the breeding grounds for the most productive careers in any field—arts, investment banking, real estate, etc. And it’s the chaos there that is the secret ingredient to creating that environment.

While I didn’t originally plan to return, I did love being back in Singapore. I was given more responsibility in my workplace and I was cooking with incredible people. Yet, something still didn’t click. I was in my late twenties and was trying to figure out my next step. I wanted it to be something significant, so I asked myself if Singapore was where I wanted to be for the next five or more years, and the answer was no. I was with my girlfriend then, now wife, and she had an opportunity lined up in Copenhagen, and we decided to move there.

I wanted to push myself, so I signed up to intern in the most difficult restaurant in the world—Noma. There, I managed to work my way up quickly thanks to my prior experience, and a year later, I was offered the head chef position.

When you are faced with a position like that, your mind starts doing all sorts of calculations—why me? Can I step into the shoes of the role? Will I live up to the work of the head chefs who came before me?

And like I did in Singapore previously, I had to think about whether this was a place I would want to be for the next five or more years because in Denmark, and this restaurant specifically, people stay for many years, even decades. It’s not the kind of place where you see your position as a temporary job. It takes time to grow into your role as a head chef, sometimes years.

Embracing new environments

Life in Copenhagen is also part of the reason why I was happy to take up the opportunity. After living in New York and Singapore, we were very used to a city lifestyle. But here, you can cycle 20 minutes one way and be in the city centre, or cycle 20 minutes in the opposite direction and be in the pure wilderness with cattle around.

Nature has become so crucial for me as it allows me to unplug in a way I couldn’t earlier. I want to be somewhere where I can step out of the house and not have to see another building or a skyline of flats. I want to see the stars and the trees.

While I can live a life more in touch with nature here, I’d say culturally, Copenhagen and Singapore are very similar, and cultural norms between the two populations are generally similar.

Danes are very open and welcoming, especially to foreigners. There’s a lot of understanding that people move around to different countries searching for opportunities. No one ever talks about foreigners in the sense of us coming here to ‘steal’ jobs.

Facing bigger challenges

Being the head chef at the best restaurant in the world was incredibly daunting at the start, and for a good reason—there are certain expectations that come with the title. But I would say, beyond any reasonable doubt, that it would not have been possible to get there if I had not left Singapore.

In Singapore, a restaurant like Noma wouldn’t exist because it is limited by its supply of ingredients. It would never be able to have a place that uses only local produce because there isn’t much beyond eggs, fish, and hydroponic herbs and vegetables. Here, we have seasons and distinct ingredients we can use at different times of the year.

Beyond that, it’s also about how opportunities that allow you to push against conventional norms are not easy to come by in Singapore. Now, there are a few more, but it was harder to come by when I was growing up. Part of that is because of the Singaporean mentality that doesn’t respect chefs as much as other careers.

That is why New York was so liberating. When people asked me what I was there to do, and I replied that I was there to be a chef, they would just say ‘oh, cool’ and move on. In Singapore, it’s like, “huh, really? Did you not have good enough grades? What went wrong?”

Lessons learned

Most importantly, moving abroad taught me empathy, the importance of being a good human being, work-life balance, and the ability not to take yourself too seriously.

Empathy is so important, specifically, being aware that someone might be going through something that you are not familiar with. You may not understand it, but that is ok—don’t have to understand. Give people the benefit of the doubt. Working in a kitchen in New York was a big equaliser because people from all walks of life were there. There were people of different races, sexual orientations, and backgrounds, but we were all working towards the same goal.

Work-life balance is also essential. Back when I started, there was this idea that you had to work 16 hours a day, six days a week. While there are strict margins in our business, we still need to keep reinventing the work wheel and changing how we work. I’ve also learned to prioritise my health, which in turn helps me at work too. If I have more time outside work to improve my mental capacity and physical strength, I will be better in the kitchen.

Last, I’ve learned to fight my own battles, especially those in my head.

When I first became head chef, I struggled with imposter syndrome. I didn’t feel like I was good enough to execute at this level. It was like I constantly had to prove myself and meet someone else’s expectations.

This insecurity is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it constantly pushes you to look at yourself and do better, and on the other hand, it cripples your confidence. Eventually, I learned that what matters most is to be a better person than I was yesterday.

I don’t need to be the best or my perfect self as long as I’m moving forward—and I don’t mean this as a chef, but as a person. To be good at whatever you do, you have to be a good human being first, especially if you are in a leadership position.