All images by Stephanie Lee for Rice Media unless otherwise stated.

When I started my RICE internship, I never imagined I’d be getting whipped. But here I am at the lift lobby of an HDB flat along Haig Road, bracing for impact.

My parents would have been so proud.

Today, I’m leaving the whipping in the proficient hands of Iswandiarjo. The whip that the 39-year-old is holding bears a striking shade of red, with an uncanny resemblance to our national flag.

I trust him. Iswandiarjo is the fifth-generation leader of Kesenian Tedja Timur, or ‘Rainbow of Arts from the East’, one of Singapore’s earliest professional Kuda Kepang groups.

Whips are a common sight at Kuda Kepang (‘Flat Horse’ in English) performances. During the performance, practitioners—while in a state of trance—withstand the force of a full-bodied lashing. Amongst other pain-defying, almost inhuman feats such as eating glass.

“Stay there,” Iswandiarjo commands.

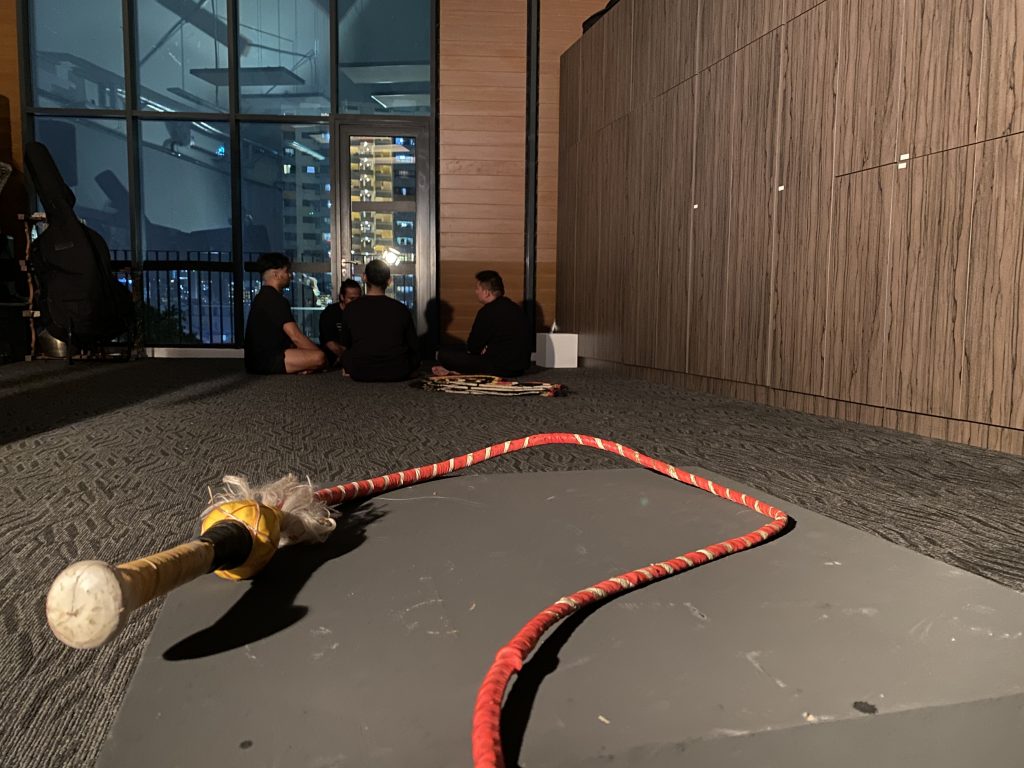

Iswandiarjo swings the whip back and forth to get a better sense of the space. Even in a spacious lift lobby, the range of the whip’s sting is remarkably vast. From the corner of my eye, I see my colleagues huddled in a corner, watching all this unfold.

Getting whipped is par for the course of my investigation. I’m here at Iswandiarjo’s abode to learn about the ancient—and in Singapore, restricted—art of Kuda Kepang. Iswandiarjo has his work cut out for him.

“Ready?” he asks. He cocks his arm back and aims.

The red hue of the whip blurs as it slices through the air. It travels at a fraction of its fullest speed, but its signature crack, albeit slightly muted, is still terrifying.

I hear the crack of the whip before I feel its impact—a testament to how fast the whip moves through the air.

With Iswandiarjo’s skilful control, the thickest part of the whip strikes and wraps around the length of my back. Despite its piercing crack, I feel no pain. Just a healthy amount of distress.

Before I can fully process what occurred only moments ago, Iswandiarjo swings his arm back again and takes aim.

“Three times. Now, it’s the second,” he says. I brace myself.

Kuda Kepang 101

“I have a thinner whip.” Iswandiarjo reaches for a second whip—this time, it’s bright yellow. “You’ll definitely feel pain with this one,” he jokes off-camera.

The whip Iswandiarjo holds spans a length of approximately three metres. It is made of braided nylon ropes, capped off dramatically in girth at its end with 30 centimetres of a much thinner nylon string. I was surprised to learn from Iswandiarjo that the whips used in Kuda Kepang can be made by anyone, as long as they have the talent.

Iswandiarjo’s childhood is closely interwoven with the art form. His father was the fourth-generation leader of Kesenian Tedja Timur, the same Kuda Kepang group that he currently leads.

Kuda Kepang, also known as Kuda Lumping, is a traditional Javanese dance art form that originated from Kediri, Indonesia. It has been practised in Singapore by Javanese immigrants as early as 1948—the year a Kuda Kepang performance was first documented here.

The dance was adapted and localised when it arrived in Singapore, performed at Malay Weddings and functions.

According to Iswandiarjo, a Kuda Kepang troupe has about 50 to 60 people, and one performance accommodates nine performers. In its heyday, a Kuda Kepang troupe could perform at weddings or functions multiple times daily.

Since knowledge about the art form is passed down from senior members of different groups, the Kuda Kepang dance has various forms depending on the troupe. Despite these subtle differences, the dance somehow always manages to capture the same intensity and regalness that has come to be associated with Kuda Kepang.

Although there are footage of Kuda Kepang performances in Singapore, I’m here to learn the Kuda Kepang dance for myself. The intricacies of the dance are lost on video—the best way to understand the art form is to experience it myself.

Iswandiarjo emerges from his house with a brown staff and a few horse puppets. The puppets are made of black rattan, with red flames embellished on both sides. “The staff is for posture correction,” he clarifies, sensing my curiosity about where the one-and-a-half-metre long stick fits into the dance.

He hands me a horse puppet. While the puppet looks thin, the sturdy rattan adds considerable weight. Holding it by its neck, I straddle the horse puppet, much like someone would when getting onto a real equine.

Barefoot in his lift lobby, Iswandiarjo uses the staff to position my feet in a T-shape. We sway forwards and back to the time of a simple one-two beat.

My feet are keeping time and stepping to the rhythm, mimicking a horse’s gallop.

Under his watchful eye, Iswandiarjo leads me around the circumference of a circle while maintaining the rhythm of the dance. With every round, the ring gets smaller. Eventually, we converge in the centre.

“This is where the performers will inhale the smoke of the incense and enter the trance state,” Iswandiarjo explains. In lieu of getting into an actual trance, he shows me a video of one of his performances with his troupe, Kesenian Tedja Timur. This time, the production takes place at the Malay Heritage Centre.

Kuda Kepang and Culture

In the video, a gamelan ensemble sits perched on an elevated platform under a tent. The mythical chimes create a heady atmosphere that immerses the audience at first listen.

As if to welcome an unseen player to the stage, the music quickens as another practitioner brings an incense burner to the middle of the circle. Performers inhale the incense smoke as they enter a trance state, inviting a djinn, or the unseen, into their bodies.

“The incense is like a gift. When I invite you to my house, I must give you drinks or food. The same goes for this,” Iswandiarjo explains.

With eyes half-closed, performers in the trance state move erratically. They hop around while spinning in circles, occasionally falling to the ground before quickly picking themselves back up again. There is a child-like wonder to their movements, cautious and uncertain yet, self-assured at the same time.

Performers possess the ability to perform superhuman feats in this state.

They chew on glass, eat lit cigarettes, and get whipped—all while maintaining an air of indifference about their actions, making the performance even more compelling to watch. Some say that these displays of bravado are absent from the original iteration of the Kuda Kepang in Java, and that these extreme feats were introduced when it came to Singapore.

Still, this is contentious—there isn’t a lot of written research determining how or why the trance element was introduced. In her paper (‘Searching for Women in Trance: Attitudes of and towards the Female‘), cultural anthropologist Eva Rapaport offers that the horse dances themselves have militaristic connotations. It can be interpreted as a display of the manly bravado of warriors preparing for battle.

It’s easy to see how eating glass, being whipped, and inhaling smoke can add to this display of machismo, though it remains to be proven definitively.

“Sometimes children might see us eat glass and think it is okay. So it is dangerous. And it is also not practical for us to put up a safety banner,” Iswandiarjo quips. I didn’t probe further, but I reckon a big disclaimer banner may look out of place in the background of a Kuda Kepang performance.

Official Stances

Certainly, displays of potentially harmful bodily displays are sound enough to discourage Singaporean Malay-Muslims from partaking in Kuda Kepang performances. The Islamic Religious Council of Singapore (MUIS) cites similar grounds for discouraging participation, citing that “there are elements in some of these performances which are objectionable in Islam.”

MUIS adds that these include the state of trance, performing acts that compromise the safety and health of both the performer and members of the public, as well as the invocation of spirits and djinn.

All these, they assert, are “against the teachings of Islam and must be avoided by Muslims at all times.”

It’s worth mentioning that the part of the dance that MUIS discourages Muslims from partaking in comes only at the tail end of a more extended two-hour performance. The trance element takes place even later.

When we inquired whether MUIS believed in the spiritual nature of the trance, they emphasised that Kuda Kepang is a cultural performance with acts that contradict Islamic teachings. They are not in the position to verify whether the trance is real or not.

Originally, the lavish two-hour shows depict great Hindu epics such as the Ramayana and Mahabharata. But in its current iteration, a Kuda Kepang performance offers a plethora of different segments. One such segment is the Indonesian Barongan dance, which narrates the triumph of good over evil.

Despite this variety, the main draw of the performance lies in the Tari Ndadi, or the trance, which can take up to 45 minutes to an hour of the whole performance.

Not On My Land, Please

Today, the puppets and the whips are merely receptacles for dust in Iswandiarjo’s storeroom. They don’t enjoy as much of the limelight as they used to.

It’s a far cry from a decade ago when his group performed weekly at the Malay Village at Geylang Serai before its closure in 2011—the last time he performed Kuda Kepang in public.

Audiences from across the island would gather at the performance square and watch the Kuda Kepang show up close. If you’re lucky, the tassel of a rattan horse will brush up against your ankles, sending unwilling shivers up and down your spine.

Now, Kuda Kepang performances are prohibited on Town Council land.

“The official reason given to us is that there are noise complaints and acts of vandalism. When we use the whip on the grass, we damage it,” Iswandiarjo explains.

I find Iswandiarjo’s stoic demeanour surprising. His responses are calm for someone whose lifeblood is considered taboo.

Perhaps, the restrictions have been here for so long that to entertain any negative emotions arising from its prohibition can feel relatively futile. The curtailment could also be the reason why many who practice this art form keep a low profile.

39-year-old Zulkifli Mohamed Amin concurs. Zul is an arts researcher and educator who has worked closely with at-risk youth for the past 10 years. He tells me that students used to be very frank and upfront about their involvement in Kuda Kepang. But due to the restrictions, things have changed.

“When I ask my current students about their involvement today, they are wary about sharing too much.”

To Enter a Trance

Centre to the controversy and misinformation about Kuda Kepang is the impression of bodily harm—some self-induced. The most visual aspect of this spiritual masochism is the three-metre-long whip used.

“The whip has two purposes. As a calling to get the performer’s attention and a warning to discipline them. Sometimes the ‘inner person’ is very fierce,” Iswandiarjo explains as we walk back to his flat, whips and horse puppets in hand.

The ‘inner person’, Iswandiarjo tells me, is the unseen spirit that enters the performer’s body while in the trance state. The same state allows them to perform grand feats of endurance and strength.

To better explain what he means, Iswandiarjo plays a video. In it, he raises his whip in one single motion, swinging it around his head before bringing it down on a performer’s back. The lash strikes with great force—much greater than what I experienced at the lift lobby.

In the trance state, however, the dancer remains unperturbed. He stands, both feet planted on the ground and continues to sway hypnotically to the rhythm.

This display of tolerance to pain is another reason why the performance is so enticing to watch. Very few things in modern Singapore come close to such a public display of blatant ferocity.

In this regard, Kuda Kepang lies just outside the realm of possibility. Through dance and art, it posits that the average human being can elevate themself to an almost indestructible state. Through years of practice and studying, a performer could go from your jolly next-door neighbour to someone who’s furiously munching on broken glass.

In his push to dispel the myth that Kuda Kepang is solely about its spiritualistic elements, Iswandiarjo introduces two ways performers can get into a trance-like state: Kebatinan and Keyakinan.

“Kebatinan is spiritualism. It takes years of practice and studying. If I am using kebatinan to eat a lit cigarette, I have to recite a particular verse before I eat it,” Iswandiarjo explains.

“Keyakinan, however, is much more grounded in reality. Keyakinan is self-confidence. When I use keyakinan to eat a cigarette, all I need is practice. Performers discover the techniques and specific workarounds to do these things.”

That’s not to say that spiritualism is not practised in Singapore’s Kuda Kepang. But not every performer uses a form of spiritualism to overcome physical pain and discomfort.

“About 30 per cent of practitioners practise spiritualism. They go to Indonesia and study. I shouldn’t say Kuda Kepang is strictly kebatinan or keyakinan. It can be both.”

A Heightened State of Consciousness

The trance element of the Kuda Kepang is central to Zulkifli’s thesis on the art form. With so much uncertainty and misunderstanding, Zul posits that disproving and invalidating its mysticism is one tenet that could bring Kuda Kepang back to mainstream acceptance.

To confirm his hypothesis that the trance is less spiritual and more psychological, Zul engaged Iswandiarjo for his experiment, ‘Kuda Kepang: An Experience’ at Wisma Geylang Serai.

Iswandiarjo is intimately familiar with this part of Geylang. He knew it as Kampung Melayu when he actively organised Kuda Kepang performances on its hallowed grounds. The performance space is also a stone’s throw away from the Al-Azhar coffee shop that Iswandiarjo frequents every Friday, at the same table, with two cups of kopi-o gajah.

For the experiment, Zulkifli recruited Iswandiarjo to teach volunteers the art of Kuda Kepang, including the process of entering a trance. Through first-hand retellings of their experience, Zulkifli discovers that our definition of trance needs to be re-examined.

“A trance could be a heightened state of consciousness as opposed to spiritual possession. The volunteers described being in the present moment during the trance,” he mentions.

“It’s like going to the club. When the music plays, people are moving.”

Indeed, while the regalness of the gamelan music is a far cry from brash EDM beats, the effects could be the same. The cyclical and hypnotic nature of the music creates an intoxicating headspace for performers to enter and embody their characters. This theory, Zul tells me, needs more research to prove definitively.

Iswandiarjo and Zulkifli do just enough to cast doubts over whether the trance in Kuda Kepang is purely spiritualistic. Of course, whether it is self-confidence, a heightened state of awareness, a direct connection to spirits—or a fusion of all—is up to us and our beliefs.

To Perform Again

True to 2022 fashion, what is prohibited in Singapore finds space online—specifically within the realms of TikTok.

In my research for this story, I took to the platform to find out the reach of its prevalence. TikTok is where I found Ajang Seni Budaya, a local cultural group that graciously agreed to host me at their training sessions.

And that’s how I find myself standing at the bottom of a dimly lit staircase of an old building that Ajang Seni Budaya calls home. The 30-odd members of the group rehearse Kuda Kepang here every Sunday between 10 AM to about 7 PM.

Walking up to the makeshift conference room, I hear the familiar chimes of a gamelan ensemble bouncing off the stairwells. It catches me by surprise. After all, a complete set of gamelan costs anywhere upwards of S$40,000.

Ajang Seni Budaya’s 18-piece setup cost them approximately S$15,000—paid for out of their own pockets. To them, it’s crucial for the art form and the music to remain as authentic as possible. Even if that means forking out a five-figure sum.

“We don’t want to talk about the spiritual elements of Kuda Kepang. We are a cultural group, focused on the dance and the art form,” one of the group’s most senior leaders declares. He has practised the art form for over fifty years and is considered a first-generation practitioner.

It makes perfect sense for the group to distance themselves from the controversy, especially when all they want to focus on is the art form and the rich culture behind it.

Initially, there was a palpable reluctance to open up to me about their views on Kuda Kepang in the conference room—an understandable sentiment given current restrictions on the art form. That reluctance gives way when I share that my grandmother was once an avid regular at Kuda Kepang performances at Geylang Serai.

“The people here are learning about their own ancestral culture. Singapore is a country of immigrants, and we are Javanese. We are not doing anything wrong. They are learning the value of discipline and hard work.”

Despite their initial stance on Kuda Kepang’s relationship with its spiritualistic elements, practitioners—at least the ones in Ajang Seni Budaya—understand that perhaps keeping its spiritualistic elements for themselves would make the road to bringing Kuda Kepang back to public spaces again much smoother.

All they want is to perform the art form freely again and keep the culture alive in Singapore.

Censoring Dignity

As we speak, the gamelan orchestra’s music penetrates the conference room’s thin walls. It’s a perfect ethereal soundtrack. Through the office blinds, four dancers—somewhere in their late 20s and early 30s—line up, ready for their turn on the makeshift dance floor.

“These people practise every week. They love the art form, which gives them something to work towards. It keeps them off the streets and away from bad influence,” another leader chimes in.

At its heart, Kuda Kepang is simply another avenue for youths to be involved in something larger than themselves. This is something that 41-year-old Jamal, a theatre practitioner and someone who has worked extensively with Malay art forms, argues.

“Who performs Kuda Kepang? People who tend to be in the lower economic demographics. At-risk youth. Underserved kids.”

“There is this negative gaze thrown around them as they go about their daily lives. But on stage, they are performers first, stereotypes second. By restricting Kuda Kepang, we are taking something of value away from them. We are removing them from their human dignity.”

As the art form dies out, we risk losing an accessible entry point for youths into tradition and a potential springboard to explore other art forms. The practitioners tell me that while they remain hopeful about Kuda Kepang’s return to the public sphere.

A more realistic outlook? It will fade away in a few decades.

“In the early 2000s, we had the Renaissance City Plan. We wanted to make Singapore more culturally vibrant. But we lack the vocabulary to do things that are avant-garde. Singapore pretends to have a vibrant arts scene. But how can we, when everything is censored?” concludes Jamal.

Bringing Kuda Kepang Back On The Road

Today, Kuda Kepang groups continue to be driven underground, away from the prying and enquiring eyes of the public. As it happens, Singapore is at the precipice of losing a unique cultural artefact—one that will be difficult to bring back if something is not done sooner.

Jamal suggests that a lack of understanding may be at the root of Kuda Kepang’s negative perceptions. After all, people fear what they do not understand. Plus, the intentional mystique within Kuda Kepang doesn’t exactly help shine a light on misconceptions.

“To the untrained eye, these practices can seem terrifying. But what if we know what it means? Then we develop an appreciation for it.”

Trance or not, Jamal hopes that the censorship of Kuda Kepang will be overturned.

“I want to encourage greater dialogue for better understanding that something like Kuda Kepang can evolve into something desirable. It can evolve into something meaningful because there are many values in it. It’s a wonderful art form.”

For now, the first step is to provide opportunities for Kuda Kepang groups to reclaim the spotlight. After all, the restrictions on the art form had worked so well that there was barely any outrage when the art form slowly disappeared.

Barring older generations of Singaporeans, mentions of Kuda Kepang get little to no reaction. The time is ripe to make headways in leading the art back to gallop on the road again.

In a time like now when the arts in Singapore are getting a considerable boost, Kuda Kepang seems poised to take centre stage once again as the Malay community’s cultural crown jewel—we only need to try.

Kuda Kepang’s rich history is too valuable to be relegated to the margins, all at the service of dividing between good and bad culture. Perhaps, it’s high time that they dust off the horse puppets, incense, gamelan, and masks and be whipped back into a glorious return.

[Editor’s Note: This story has been updated on 03/10/22 to reflect MUIS’ response.]