All images: Zachary Hourihane

Nearly three decades since settling in Singapore, my Irish mum’s sense of home has both narrowed and evolved.

“In a year or so I will have lived longer in Singapore than in Ireland,” she said.

“But as much as I love Singapore,” she continued, “I have a stubbornly Irish heart.”

There’s a special kind of love and longing that my mother, Jacquie Hourihane, feels for the emerald isle, where she was born and raised for 27 years. “In Gaelic, it’s called a grá. I have a grá for Ireland.”

In absentia from the motherland, Jacquie’s Irish heart has only beaten stronger—strong enough to carry a powerful love for her home away from home: Singapore.

“I can’t replace my grá for Ireland, nor do I want to,” she said. “But that doesn’t mean I don’t belong here, or that I can’t love it fiercely, as well.”

Since arriving in 1994, she noticed a key similarity between her nations: scrappiness.

“Singapore and Ireland are more alike than they seem,” she said. “Both are ex-colonies that battled hard, recently, for their independence.”

Integration vs Assimilation

Integration thrives with recognitions like these: the world is vast and varied, but there are universal experiences that unite us. I’ve explored this issue for RICE from many angles—usually through profiles I don’t personally know.

I hadn’t thought to ask my mother, now a Singaporean Permanent Resident for well over a decade, how she felt about this issue which has grown fraught over the years. She’s been here a long time, after all.

Her perspective surprised me.

“There’s a difference between integration and assimilation,” she explained. “I think the former can be achieved without the latter.”

In her eyes, integration accepts the different life experiences of immigrants and expats on the condition that an intuitive, good faith understanding of the norms and values of Singaporeans must emerge.

Assimilation, in her view, is a more total process of ‘becoming’ Singaporean—naturalization, in the cultural sense. “Which is the right path for some people,” she said. “But I’m proudly Irish.”

She doesn’t consider her grá for Ireland as an obstacle between her and Singapore. Is it necessary to surrender one home to create another?

“You can have more than one home. One strong connection doesn’t cancel out, or weaken, another.”

She hadn’t intended to stay for so long—just a couple of years. But life comes at you gradually until it doesn’t. The quick sojourn has turned into something else. Part of why our family is so rooted in Singapore has a lot to do with my mum.

And 27 years later, here we still are.

Fish Out of Water

“It was pissing rain at Dublin airport on the day we left,” my mum recalls. It was January 1994, on the day of my grandfather’s birthday.

Many years later, my grandfather confessed that he wasn’t sure when he would ever see her again. Back then, when Irish people left Ireland, they rarely returned.

When the plane touched down in Singapore, Jacquie was immediately engulfed in the sweltering heat. “After 27 years, I’m still not used to it,” she laughs.

Her acclimation was a baptism by heat and humidity. When my parents arrived, they knew no one other than my dad’s colleagues.

To get her bearings, Jacquie wandered around. She walked the whole city in one month. She had time on her hands. “While your dad was at work, I just showed up to the places I’d heard of and scoped them out.”

She walked without a map, asking for directions along the way. She was treated with respect and hospitality, particularly by the older generation. “Everyone was so kind, and curious––they asked me why I was here, for how long I intended to stay, and so on.”

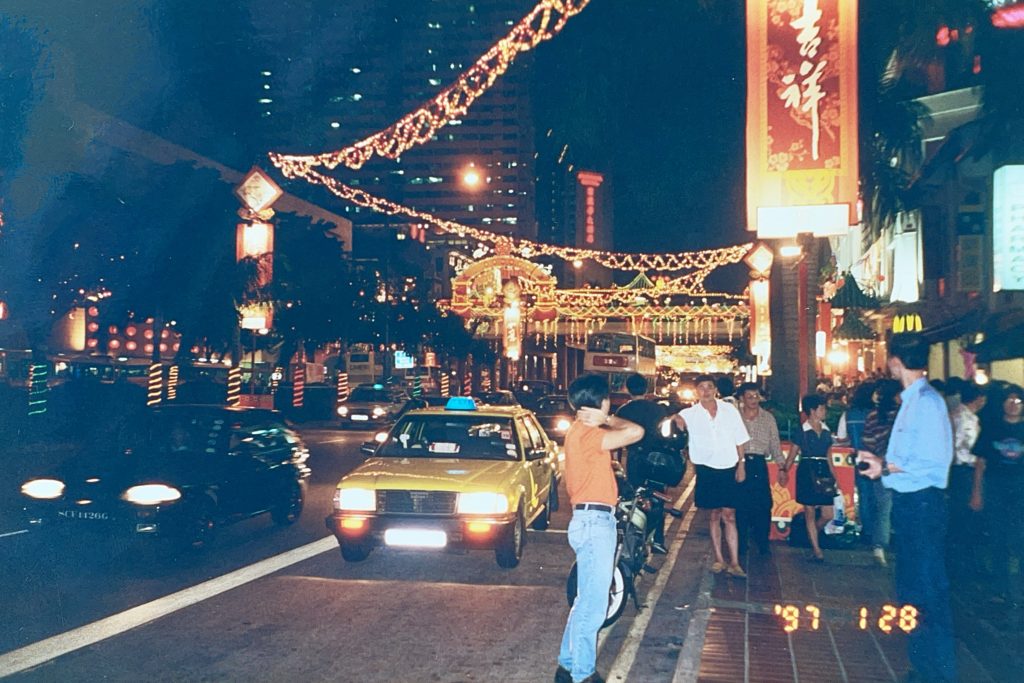

For an Irish woman in her mid-twenties, Singapore’s melting pot was thrilling. She was enamoured by the different cultural quarters, like Arab Street, Little India, Holland Village, and Chinatown.

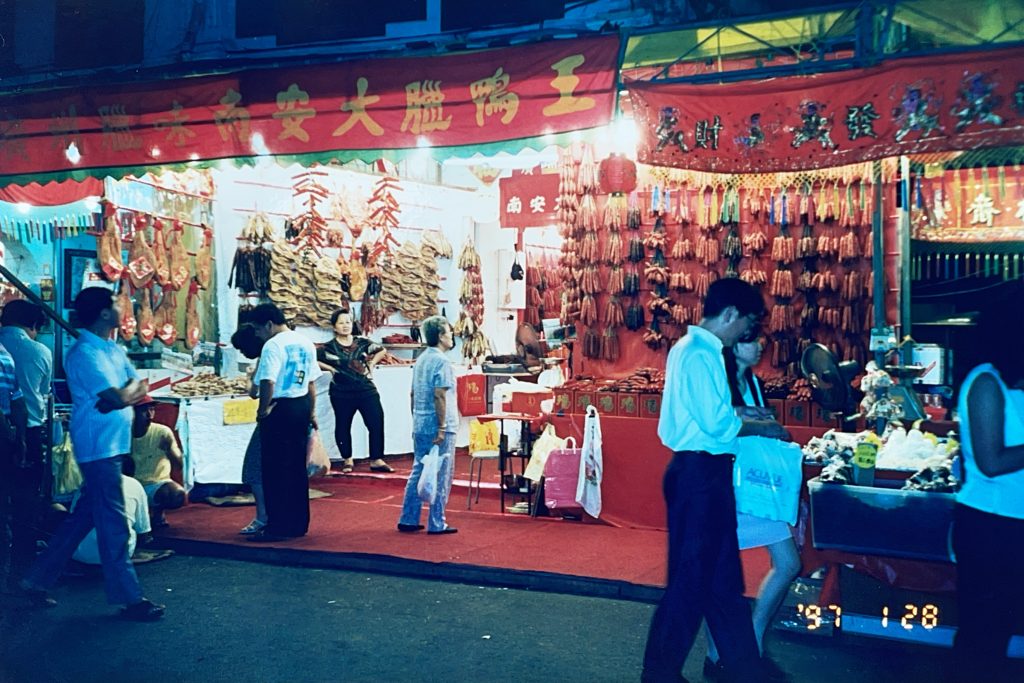

Back in the ‘90s, she remembered them as more defined. “I took the bus into Chinatown every day for the first couple of weeks. I just loved it there, talking to the aunties, learning about herbal medicine.”

Moving into their first apartment in Spanish Village along Farrer Road was the first logistical step. “We didn’t have an expat package, so we found and paid for the apartment out of whatever your Dad earned.”

An estate agent called Elaine picked her up from their hotel, The Plaza (now the Park Royal) on Beach Road for the first viewing.

“Colleagues of our agent bumped into her on the street. They kept saying, Elaine-ah. You know, Singlish. Duh. It’s so obvious now, but back then I had no clue. I thought her name was Elaina. So I started calling her that and she looked at me like I was crazy.”

They had a good laugh afterwards. Their move-in date to Spanish Village coincided with Chinese New Year, which happened over a long weekend.

“Of course, we didn’t know anything about what happens during CNY. Not a single store was open. We moved in with literally nothing—I needed toilet paper, kitchen roll, dish soap, and the works. Even the petrol station shop was closed.”

Eventually, she pilfered some toilet paper from a hotel to tide them over.

Shortly after moving in, Jacquie was summoned to a government building to review a videotape of her cousin’s wedding that was sent in the mail. “I sat there with a few of the––I don’t know what to call them, censors I suppose?––and we watched the wedding video all the way through.”

She presumed they were screening it for pornography or otherwise inappropriate content. In hindsight, perhaps this was carried out by a film content assessor from the Board of Censors, founded under the Films Act in the ‘80s.

For an Irishwoman, this was an unusual process. It seemed, to her, even a little bit silly. But watching her cousin’s wedding ceremony with the censors sparked a perspective she’s kept throughout her life in Singapore: “I am a guest in a different culture and I should behave accordingly.”

18 Months of Rendang, Sweat, and Tears

It took 18 months for my parents to settle comfortably in Singapore. For Jacquie, building her own life, independent of her husband, was the key to laying down roots in Singapore.

Having taken an ESL course before emigrating, it wasn’t long before she was hired by an enrichment centre to offer speech, drama, and creative writing classes in local schools. Her first appointment was in Pei Hwa Primary School, reading to 5-year-olds and teaching the alphabet.

As a Caucasian teacher, she was an oddity to her pupils.

“The little girls twirled my hair and asked to brush it. I don’t think they’d encountered many blonde women before. They adored me and I adored them.”

Like any teacher, she had her favourites: “There was one little girl with a blunt bob and a serious face. She just looked wise beyond her years. One morning, I was reading a book of nursery rhymes—and she yelled out very seriously, while I was reading: ‘Cow SO fat… how can it jump over the moon?’”

Because the enrichment centre was short-staffed by English teachers, she commuted across the island daily. “There were days when I went from Upper Bukit Timah to Bishan and then Tampines.”

Back then, her bus routes weren’t air-conditioned. “I didn’t mind it, though. I wanted to experience all of Singapore, not just the expat parts,” she said.

Weekends were cherished for culinary occasions. Irish diets are rich but repetitive—meat (beef, pork, chicken) and vegetables (greens, carrots, potatoes) were the dinner staple. So Singapore’s advanced palette was enticing to my parents.

For a while, it was all about the beef rendang. “Arab Street had the best one, and the Cricket Club was good too,” my mum remembers. Together, they also frequented The Satay Club on Queen Elizabeth Walk, which was later demolished in 1995 to make way for the Esplanade.

But above all else, Indian food was their true love.

“Race Course Road had the most unbelievable restaurants,” my mum recalled. Thanks to its butter chicken, The Banana Leaf Apolo was one of their early and enduring favourites.

Although teaching and eating were the ties that bound her to Singapore, after a year or so, debilitating homesickness kicked in. At-home internet was a luxury they couldn’t afford, and long-distance phone calls were infrequent because they were so expensive.

Born in Singapore, Not Singaporean

That’s what my birth certificate says, stamped above the location: Mount Elizabeth Hospital. It’s a neat explanation of the shaky sense of ‘home’ I’ve developed over the years.

Since I’ve never lived in Ireland, I feel more attached to Singapore. But I wouldn’t call myself local, either. My Mum pointed to this tug-of-war as the sore spot for integration.

“This is the central problem, right? Emotionally, I mean.”

“Expats can be rooted in two places, but also torn between them.”

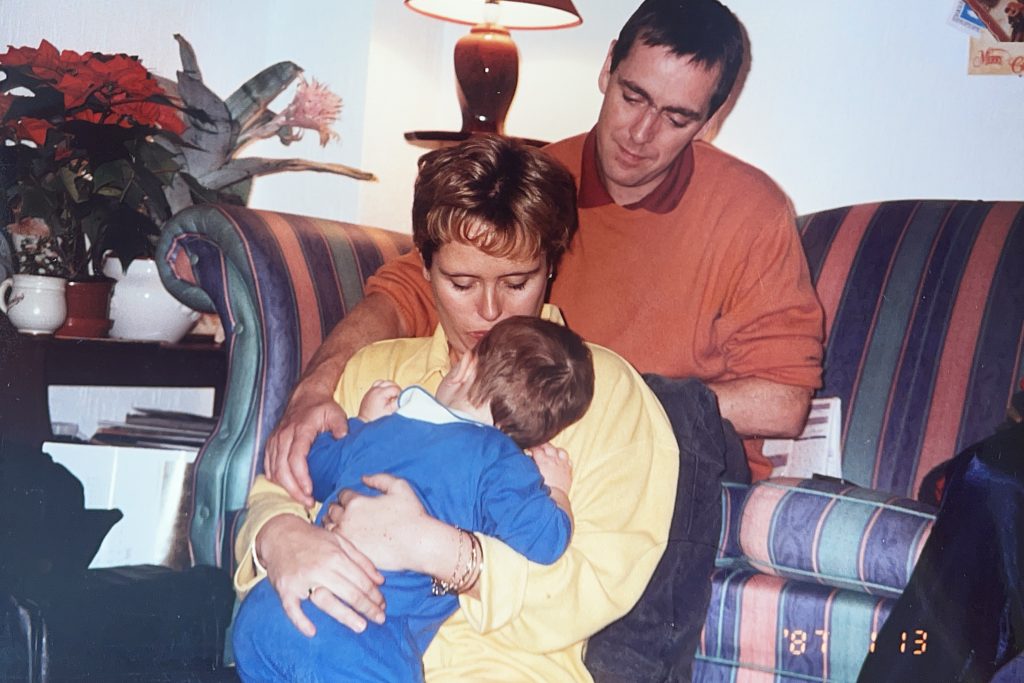

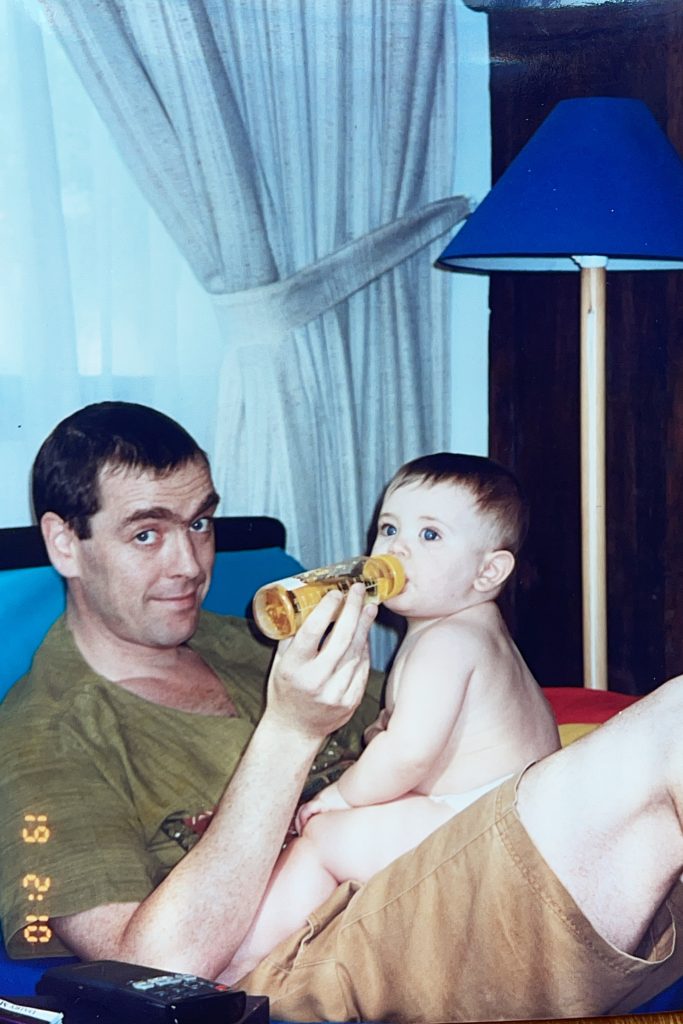

She felt a competing rootedness after she gave birth in Singapore. “I had a very difficult pregnancy, and you were born so prematurely that it was quite scary.”

The medical care she received was phenomenal, but when all was said and done—because my Dad frequently travelled for work—she was on her own at home with an infant quite a lot.

While he was away, she sorely missed the support of her female relatives and friends back home. In particular, she yearned for the comfort and wisdom of her own mother.

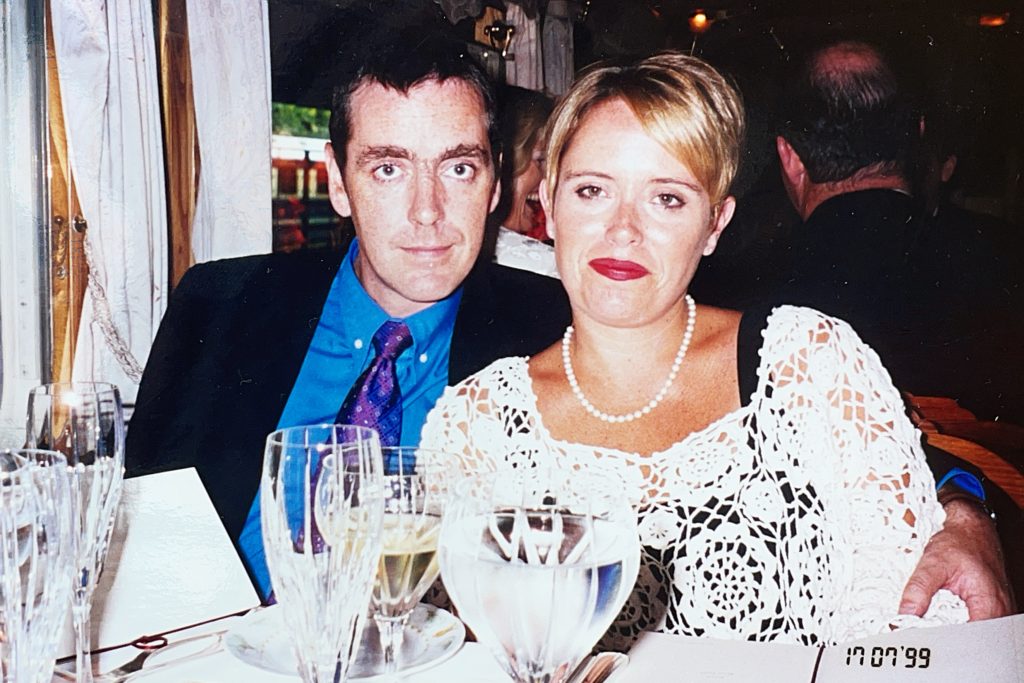

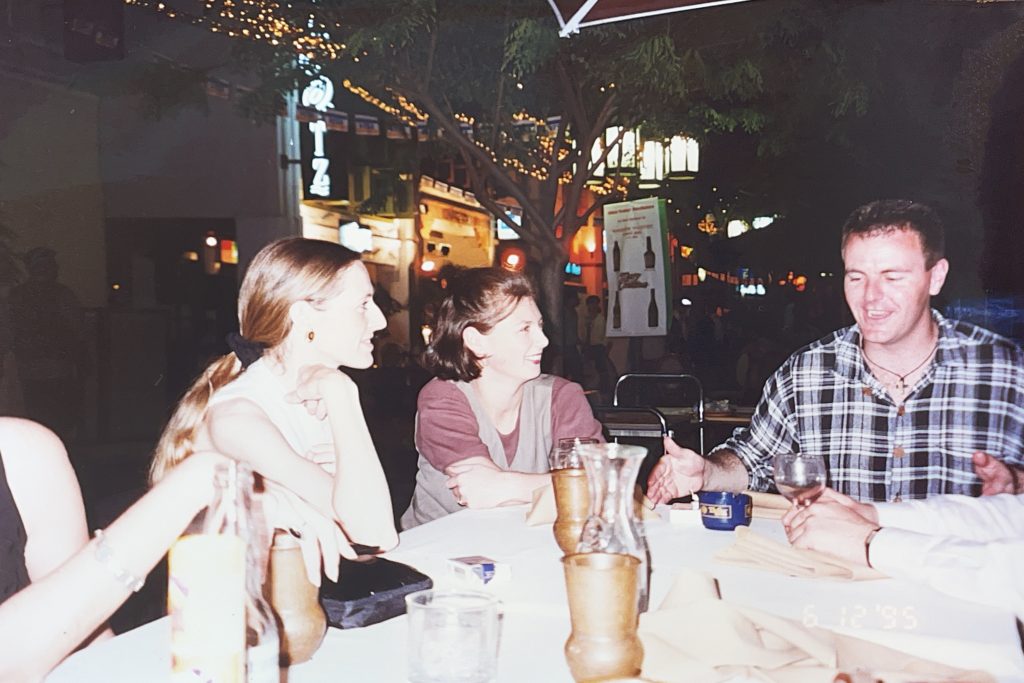

It was at this juncture that she cultivated strong relationships with other expat women: “They really stepped up and filled this role I had been missing. We’re all in the same boat, here, right? I did the same for them with their babies. All we had was each other. When you’re far from home, your friends are your family.”

She thinks this is why expats can be perceived as cliquey and insular: “We build our own micro-communities in Singapore to feel seen and understood. Cultural differences can make socializing more complicated. Not difficult, or impossible, but complicated.”

In her experience, having a sense of familiarity made her a better-integrated foreigner in Singapore. She felt more at ease and empowered in making Singapore her home in a community of people with familiar cultural references as her.

Building a Micro-community

By the time I was in secondary school, my parents were tired of living ‘on the fly.’ Their two-year exploratory adventure became an emigration. When they received Permanent Residency in 2008, it was like a weight lifted off their shoulders.

However, the change in status didn’t significantly impact their perception of Singapore. By then, it was already home for over a decade. “It was a technicality; I didn’t suddenly become more integrated because of my PR status,” she said.

After I was born, Mum wanted more flexibility in her work schedule than what teaching could offer––so she got involved in the local fair scene. It was mostly expat women, then, as vendors. They supplied local shoppers with imported goods.

She was working on a Letter of Consent (LOC) from her Dependence Pass (DP) then, as were most of her colleagues. The LOC is an authorization certificate issued by Singapore’s Ministry of Manpower (MOM) that allows eligible LTVP (Long-Term Visit Pass) or LTVP+ holders and business owners to work for a Singapore company.

Though she’s been a PR for a number of years and doesn’t consider herself an ‘expat’ anymore, she felt sorry when she saw that LOC’s were no longer being given to DP holders in 2021.

“Most people availing of the LOC are expat women. They aren’t drawing huge salaries by designing jewelry and selling at sporadic pop-up shops. I don’t see how they are taking jobs from Singaporeans as small business owners.”

The legislative change reminded her of how important it was to create a sense of agency while putting down roots in Singapore.

“The women I know who are affected by this change want to be involved in the community. They volunteer, work with animal shelters, and run small businesses. It doesn’t seem like a net positive to stop them from doing these things.”

Over the years, Jacquie has embedded herself in the small business community. Throughout the pandemic, she noticed that some of the ‘legacy’ brands (especially the ones owned by expats) had disappeared.

However, she was pleasantly surprised at how many locally owned independent brands and designers had emerged when the dust settled. As she’s well-known in the industry, some of the new players reached out to her for advice on growing their businesses.

After organizing a socially-distanced fair in 2021, she opened a shop—Cove Collection—in Sentosa to showcase locally grown small businesses, where each brand owner pitches in a couple of hours per week to run the shop and sell everyone’s wares.

It was crucial for her to include a diverse range of vendors, with a healthy mix of locals and expats. She’s been able to link one of her favourite local vendors, Jessica, with other collectives and stockists in Singapore, to increase her reach and help grow her business.

“I know how it feels to build something from the ground up. I want to make it easier—and more fun—for other women in Singapore, as well.”

For the Long Haul

“Home is a feeling, not a place. You don’t have to be in one place forever to call it home,” my mum said, reflecting on whether she even feels like an ‘expat’ anymore.

She’s been in Singapore long enough to have discomfort over being categorised as a ‘transient’ visitor. However, she understands why expats can get a bad rep.

“I’ve met some over the years that, quite frankly, I’ve hated. They breeze through, pay little tax, spend to show off, and treat people badly. But there are more long haulers than you might think—those who intentionally placed roots and brought Singapore into their hearts.”

In her experience, especially after the pandemic, there are more long-haulers than flighty visitors. It’s harder now than it was when she arrived to move here on a whim and pitch up spontaneously. Throughout this interview—and many times over the years—I’ve tried to get an answer to when she plans on leaving Singapore.

She is always cagey about committing to a date. For as long as I can remember, the answer has been “a couple more years.” But the years add up on themselves, and soon she will have lived away longer than she’s lived in Ireland.

One thing she knows for sure is that a part of her belongs to Singapore forever.

“I will be completely, utterly heartbroken when I leave. Whether I live here or not, it will always be my home.”