All photos courtesy of Eunice Sng unless otherwise stated.

A chorus of cheers erupts from the grandstands of Singapore Turf Club every half an hour.

“Zao! (Run), Sa Ho! (Number Three)”, punters exclaim and call out their chosen horses’ numbers in Hokkien, raising their fists to the skies as thundering hooves charge toward the finish line.

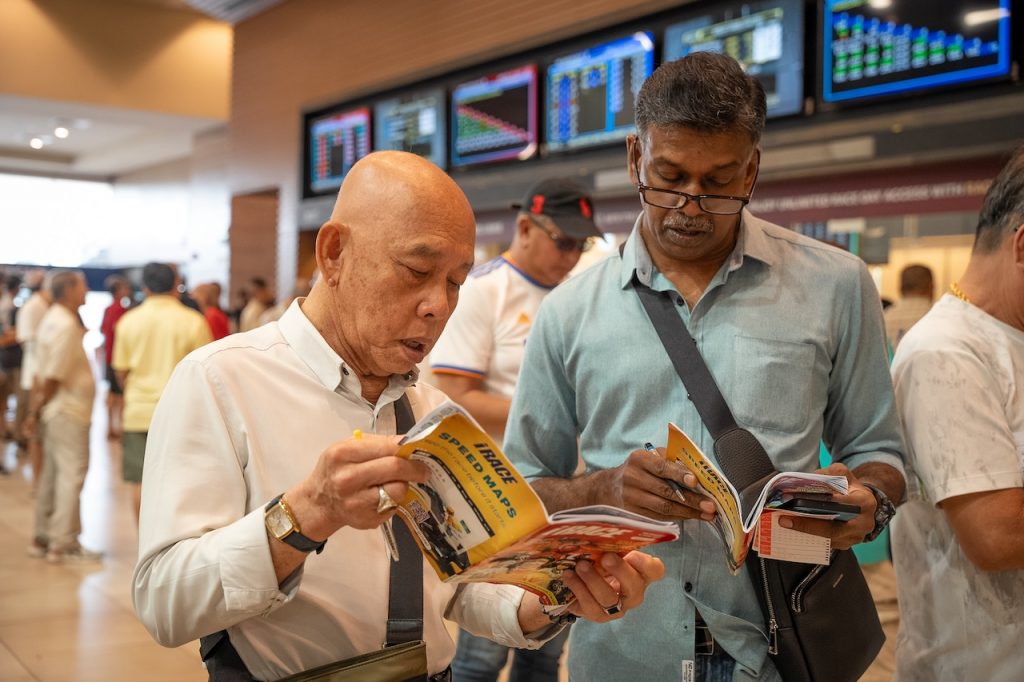

Amidst the brief explosions of energy, one fact stands out: the gamblers are predominantly ageing Chinese men. Entering the Turf Club feels like stepping into another world, one ruled by the elderly. In the crowd, gap-toothed grins and crinkled eyes intently focus on the action.

As we wander through the venue, our feet crunch on discarded betting slips; our noses twitch against the constant plumes of cigarette smoke despite the prominent “No Smoking Indoors” signs. Empty blue Tiger beer cans litter the seats.

Betting on horse races is these elderly punters’ favourite pastime—a weekly reprieve from the drudgery of daily life. But soon, punters will lose this avenue for live entertainment when the Turf Club holds its last race on October 5th, 2024.

This will mark the end of almost two centuries of horse racing in Singapore, and with it, the community and microculture attached to the sport.

“It affects them on multiple levels. One is that they will no longer have that place to meet the people they usually meet regularly,” says Dr Andy Ho, a social scientist from Nanyang Technological University (NTU) specialising in psychosocial gerontology.

“It could also lead to them losing what usually gives their lives meaning, like that sense of connection and identity that they belong to this group of people. They hang out, drink coffee and talk about horses, which might give them a sense of purpose.”

Singapore is rapidly becoming a ‘super-aged’ society, with more than one in five people expected to be aged 65 and above by 2026, according to The Straits Times. This makes it all the more crucial to consider the recreational needs of a growing portion of the population—even if it does have inadvertent ramifications.

Tang Hoo Huat, 68, the owner of a convenience store at the nearby Kranji MRT, says: “Some of the punters got a heart attack and passed away while watching the races. It’s a very anxiety-inducing hobby.”

Speaking in Mandarin, Hoo Huat added that over the 17 years he has operated his shop, many of those who used to be his regular customers suddenly stopped visiting because they passed away or lost their ability to walk.

The ageing demographic partly explains why horseracing has become less popular—average spectatorship dropped 74 percent from 2010 to 2023. Only about 2,600 people now show up at the racecourse weekly. The sport failed to attract a new generation of followers who have many other entertainment options, and after the Covid-19 pandemic—which suspended racing for a time—race day attendance fell steeply.

Punters reminisced about the heydays in the 1980s when all three floors of the old grandstands at the club’s previous location in Bukit Timah would be packed with 60,000 people. The current racegoers at Kranji are the remnants of that era.

Blast From the Past

Overflowing car parks, women dressed in multicoloured dresses, and a visit from the late Queen Elizabeth II. As we flip through photographic archives of the Turf Club from the 1970s and 80s, we’re struck by how closely the race day atmosphere resembled sold-out arena concerts.

Now, glaring chunks of empty space pervade the stands in Kranji. The second storey remains closed because there is no need for additional seating. It’s almost as if each unclaimed seat represents a missing punter lost to old age over the years.

Rows of seniors still queue up diligently to pass their betting slips at the counters and pay with physical notes. Even though the Singapore Pools app allows them to place bets digitally, most punters prefer sticking to what they are used to.

We notice a familiar individual pacing the grounds every week: 68-year-old Ho Chye Hua. As we make eye contact, he grins and calls out in Mandarin, speech slurring from his dentures, “Young ones! You’re here again.”

Chye Hua has been a patron for the last 40 years. He recalls how, in earlier days, the atmosphere at Bukit Timah was like a “warzone”, with people snatching money, quarrelling, and getting into tussles with policemen. Police officers would then round up the offenders in buses headed for the police station.

“People would bring bags of cash to bet. Some always drop on the floor, and you can just pick it up,” he chuckles.

The Kranji racecourse is muted in comparison. The ‘wildest’ incident we witnessed was a lone punter suddenly yelling out a stream of expletives in Hokkien while stomping his feet after losing a bet. Others simply glanced at him amusedly before turning their attention back to their betting booklets once he ran out of breath.

While shutting down a place with a notorious reputation may seem better for society, the Turf Club plays an important role in the lives of the elderly individuals who frequent it beyond the act of gambling.

Pastimes

Horse betting offers these seniors in their 60s to 90s— usually from the working class—a way to pass the time during their retirement. It’s an alternative to staying home and milling about the neighbourhood coffee shops.

“I don’t have many other activities to do and don’t know where else to walk, so I come here,” says punter Ng Kwang Hock, 74, in Mandarin. “I drink a can of beer and stay for a few hours, then go back home.”

“Last time, when the Turf Club held more races in a week, walking around inside was a good way to kill time,” Zhang Ah Liang, 66, chimes in.

Another punter, 72-year-old Ng Choon Kee, shares that it “has become a habit” since he has been doing it for the past five decades. He started betting when the Bukit Timah Racecourse was still around. He says he will be “very sad” once the Turf Club closes and that he’ll “miss the feeling of winning”.

Gambling at the Turf Club gives them something to “stimulate them mentally” and direct their energy towards since most of them are no longer working and their children have all grown up, according to a 2018 sociology thesis titled Racing From Alienation: Horse Betting As A Safety Valve Amongst Elderly Chinese Punters at the Singapore Turf Club by National University of Singapore (NUS) graduate Choy Yun Zhen.

Most of them do not have other fulfilling hobbies outside of horse betting.

“There’s only a few things to do. Very simple: watch TV, gamble, and sleep,” says Ah Liang.

The paper goes on to describe how these elderly punters feel isolated from mainstream society. They hold an underclass status because they no longer actively contribute to the economy and command less authority in the household.

Such is the case for Ah Liang. Although he lives with his children, he feels lonely and bored at home because “old people and young people don’t mix well”. Since their children have entered adulthood and built their own lives, they no longer have to rely on him.

Yun Zhen’s thesis explained how the elderly punters used to be breadwinners and spent the majority of their time outside working. Now that they stay home, their “extended presence [in the domestic sphere] is unwelcome by their family,” pushing them to the racecourse.

Over here, forking out part of their savings on betting is a form of leisure, relieving them from the frustration of their daily lives.

“What’s the point of leaving all my money in my bank after I die? It’s no use to earn so much and then keep it. Might as well use some here,” says Leong Chee Kwan, 62.

The punters, resigned to their mortality, know they are merely playing the waiting game. The Turf Club offers a familiar haven as they idle away the days to their end.

Perceived Power

Before a race, punters crowd in front of a parade ring where they watch horses being led around the loop. The seniors scrutinise their race guides and Chinese newspapers for information on the steeds before placing a bet. Some whip out a pair of binoculars to get a closer look at the horses’ body language.

“This is already my fourth or fifth pair of binoculars. The rest broke, so I had to buy a new one,” one uncle says.

“In the past at Bukit Timah, the horses didn’t come up that close, so if you didn’t have the binos, you couldn’t see anything.”

Horse betting is a complex game that needs a level of expertise. The guides contain details on the horses’ racing history. From this, punters analyse and decide which horse they want to pin their hopes on.

Since the hobby requires inside information, it gives these old devotees a temporary sense of control that compensates for the powerlessness that they feel in their day-to-day existence, according to Yun Zhen.

The author further elaborates that they can “assume an alternative identity that” does not exist beyond the Turf Club’s gates, such as being a horse racing expert. This makes them feel empowered because it is a more “prestigious” position than being stuck at home and seen as a nuisance to family members.

The punters feel proud that they have been dedicated to horse betting for multiple decades. Hence, their advanced age and accumulated experience bestow an illusion of authority over their lives.

But, of course, the hobby is merely a distraction. Yun Zhen’s thesis emphasises that any power they perceive to hold at the Turf Club vanishes once they walk out. Their horse betting knowledge does not benefit them outside these gates.

Third Spaces

Other than power, the Turf Club offers a loose sense of community. Often frowned upon by society as a vice, gambling here allows them to be equals among peers, indulging in their hobby without fear of judgment from their families.

“Here, I have a group of horse betting friends. We can gather and discuss horse betting topics. So even though I can just watch the races on my phone, I choose to come here,” says Chee Kwan while sitting at the parade ring.

Chee Kwan adds that he does not actively seek these friends out but greets and talks to them for short periods when he bumps into them. The connections are fluid. Though brief, these casual networks they form also help to relieve the isolation they feel.

The same goes for a punter who only wished to be known as Guan, in his 60s. Familiar faces would nod their heads at him and make hand signals on which horses they are betting on, and he claps their shoulders and shares kopi with them.

Sam Lee, 65, makes that coffee. He runs a drinks store in the Turf Club, offering hot, cold, and alcoholic beverages to the punters who spend the day there.

Sam laments the closing of the club and confesses that he worries about the regular punters who come to seek social interaction and occupy their time.

“You need to treat this place like a place of heritage. It’s not just about gambling. There are 181 years of history and memories here,” he remarks.

“If this place closes, there’ll be two scenarios for many old people in Singapore. One, spend their time at coffee shops—but how long can you go on like that? Another one is to just wait until their time is up.”

Another punter who feels the loss keenly is David Choong, 78. Armed with binoculars and a tidy organisation of newspapers around him, he introduces his two friends.

“But most of my friends don’t come anymore, and some are…” he trails off. His eyes glisten with tears before he collects himself.

“Why wouldn’t I be sad? These are all old friends. Why wouldn’t I think of them? I meet some below my block, but I’ve lost contact with so many,” he says.

David adds that although he knew the Turf Club’s closure was inevitable, he still feels it is a waste for Singapore to remove one of the older generation’s main sources of entertainment.

“Not being able to see familiar faces anymore, it makes me feel…” he sighs. “We’ll still talk over the phone, but it’ll definitely feel different.”

The bedrock of friendships among elderly punters would be lost, robbing them of their sole leisure activity.

Such a loss could significantly impact their mental well-being. NTU social scientist Dr Ho explains that older adults from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are at higher risk of depression. So, the Turf Club punters are especially vulnerable. And although longevity among Singaporeans is increasing, people are not ageing healthier.

“Mental health among the elderly is quite poor. Research has shown that if you’re lonely, the impact on someone’s holistic wellbeing can equate to having 15 or 16 cigarettes a day,” adds Dr Ho.

Déjà Vu

This is not the first time the horse racing community has experienced loss. When the Turf Club moved to Kranji in 1999, many staff who worked at the former Bukit Timah site and their families had to relocate from the Labourers’ Quarters, the only home that they ever knew.

Tamilsegar s/o Rama, 56, now a driver for snack items, was one of them. Tamilsegar lived there for 30 years when his father was head supervisor of the racing track and he was a track rider.

He talks about how the Indian workers would gather to pray to deities at a small temple in the quarters set up by the Turf Club management and listen to music in a multi-purpose room. The Indian community also organised traditional events, inviting the other Malay and Chinese workers to join the celebrations.

Tamilsegar was so attached to the place that he chose not to vacate the premises and stayed on to the final day, even when everyone else left. Friends and family members had to convince him to leave when the authorities closed off the Bukit Timah area at the turn of the century.

Until mid-2023, Tamilsegar would go through the broken fences and record tours of the abandoned dormitory buildings, talking about his memories there. He also shares photos from that time on a private Facebook group called TCIB, short for ‘Turf Club Indian Brothers’.

It has been more than two decades, but his face still comes alive when we ask him more about his days at Bukit Timah. Tamilsegar gets emotional.

“Going back there brings tears to my eyes. How would you feel if your home was taken away from you?”

End of the Line

With the horse betting hub on its last lap, what can be done to help these older persons find meaning in their golden years and safeguard their mental health?

Dr Ho, who studies creative ageing, mentioned alternative art forms that seniors can explore.

“A lot of older folks in my research talk about culinary arts, horticultural therapy, and storytelling,” he said. These are what seniors in the community value,” he offers.

“They want to be able to share their experiences with future generations because they have lived a long life. Being able to retell these stories helps them to have a stronger sense of personhood, and that can lead to great mental health outcomes.”

He also emphasised the importance of physical exercise and talked about how different types of exercise can be promoted at senior activity centres to cater to their varying tastes.

But elderly punters are creatures of habit, so introducing these activities to them might be an uphill task. To bridge this gap, Dr Ho suggested that the government consider deploying social workers and volunteers at the club to set up roadshows.

“During these few final months, the volunteer welfare organisations (VWOs) can station some booths there with brochures to engage the seniors,” he says.

“These VWOs can expose them to other kinds of hobbies and even identify groups of seniors who’ve been together gambling for a long time, inviting the whole group to try something new.”

Dr Ho stressed: “This is a great way to engage them in a timely manner right now. Because once this place closes and they all go back to where they live, then it’s really hard to catch them.”

From Yesterday

Singapore has raced down the highway of progress in recent decades, but such rapid advancement often means leaving behind aspects that have long been integral to older generations.

At the Turf Club, we spot people on mobility scooters. Others grip walking canes. Some totter back home by themselves at days’ end. We see weather-worn faces sitting alone, looking wistfully across at the track and screens. Melancholy is rife.

As we leave, we see one gentleman above the parade ring who has not moved from his seat since we saw him at the start of the day. He holds neither betting slips nor newspapers, unlike the others. When we catch his cataract-clouded eyes, he gives us a ghost of a smile, disappearing behind the top of the escalator.

This is the generation clinging to the last vestiges of familiarity and bygone glories. We cannot help but feel they know they are on borrowed time—and all they want to do is spend it doing things they have always done.

Like the horses galloping past, we cannot help but feel we have left them behind.