Top image: Stephanie Lee / RICE File Photo

In Singapore, you’re ‘allowed’ to fall sick a maximum of 14 days a year. In Australia, it’s 10 days. In Norway, you could be sick for an entire year and still receive your wage.

It’s strange that something as universal as falling ill is treated so differently across the world. And in Singapore, it just might get harder for workers trying to call in sick these days.

The Ministry of Health (MOH) is looking to curb the “excessive issuance” of Medical Certificates (MCs), it said in a circular released jointly with the Singapore Medical Council (SMC) on April 22nd. Teleconsultation platforms came under scrutiny in the circular after feedback from employers and government agencies.

The circular alleged that patients who weren’t sick were issued MCs to skip work or school, calling this “malingering and abusing medical leave privileges”.

With the rise of teleconsultation platforms, it’s been easier for workers to obtain MCs without waiting in line at the doctor. Perhaps too easy.

According to the circular, medical practitioners on these platforms allegedly issue MCs based on the ailments patients enter into the system “without any proper assessment” of underlying health conditions.

To curb the issue, the authorities are considering mandating that a medical practitioner has to provide care to a patient in order to issue an MC. Another proposal is for the doctor or dentist to include their name and medical registration number on the MCs they issue.

This might be a tough pill to swallow, but making MCs harder to get isn’t going to stamp out malingering.

MC Culture Through the Ages

It’s funny. Most employers require employees to furnish an MC to qualify for paid sick leave, yet get all up in arms when employees do it. For some reason, requests for paid sick leave are eyed with suspicion.

This culture of distrust in the workplace isn’t new by any means. Back in the ‘70s, some civil servants turned their noses up at MCs issued by private doctors, preferring government doctors.

A Straits Times article from 1975 described how The Chinese Middle School Teachers’ Union suggested that principals should only accept MCs from government doctors to “clear all doubts whether their teachers were genuinely ill”.

Fortunately, the Ministry of Education pushed back: “What is the point of having bona fide private doctors if the Government will not accept medical certificates issued by them?”

Go back a decade or so to pre-independence Singapore, and you’ll find the same issue cropping up in workplaces. In 1959, a tractor company made headlines for refusing to accept MCs issued by government doctors unless they were counter-signed by doctors employed by the company.

Fortunately, we’ve come a long way from when companies only trusted their own doctors to certify their employees unfit for work. Nowadays, most employers accept MCs from private doctors and telemedicine providers such as MaNaDr and DoctorAnywhere.

As the recent MOH circular has proved though, some of them do so grudgingly, viewing employee’s sick leave requests in bad faith.

Here’s what employers seem to have trouble grasping. How employees get their MC doesn’t matter—be it with an in-depth consultation or a minute-long Zoom call. If they don’t feel like working, they won’t. And you’re going to have to take their word for it that they’re going to be unproductive for the day.

All MCs rely on some level of self-reporting of symptoms. And with conditions like migraines and headaches, the symptoms can’t exactly be physically verified. If a patient turns up at the doctor’s complaining of a headache, it wouldn’t be ethical to turn them away, would it? The right thing to do would be to give them the benefit of the doubt.

Regulating MCs to ensure doctors adhere to medical ethics is one thing. But to do so as a way to police workers just isn’t going to work—it would be a step back.

Malingering: Can It Be Justified?

The uncomfortable truth is that workers sometimes take a sick day when they aren’t actually sick. Maybe they’re on the cusp of falling sick and need some rest. Maybe they find they can be much more productive at home if they skip the commute for that day. Maybe they’re burnt out and need a mental health day. Maybe they’re dealing with personal issues.

And unfortunately, there are some bad apples who just want to shirk their work responsibilities.

I get why this doesn’t sit right with employers. But malingering is the symptom of something gone wrong in our workplace culture. Trying to stamp out the “abuse” of MCs without addressing this root cause won’t do anything.

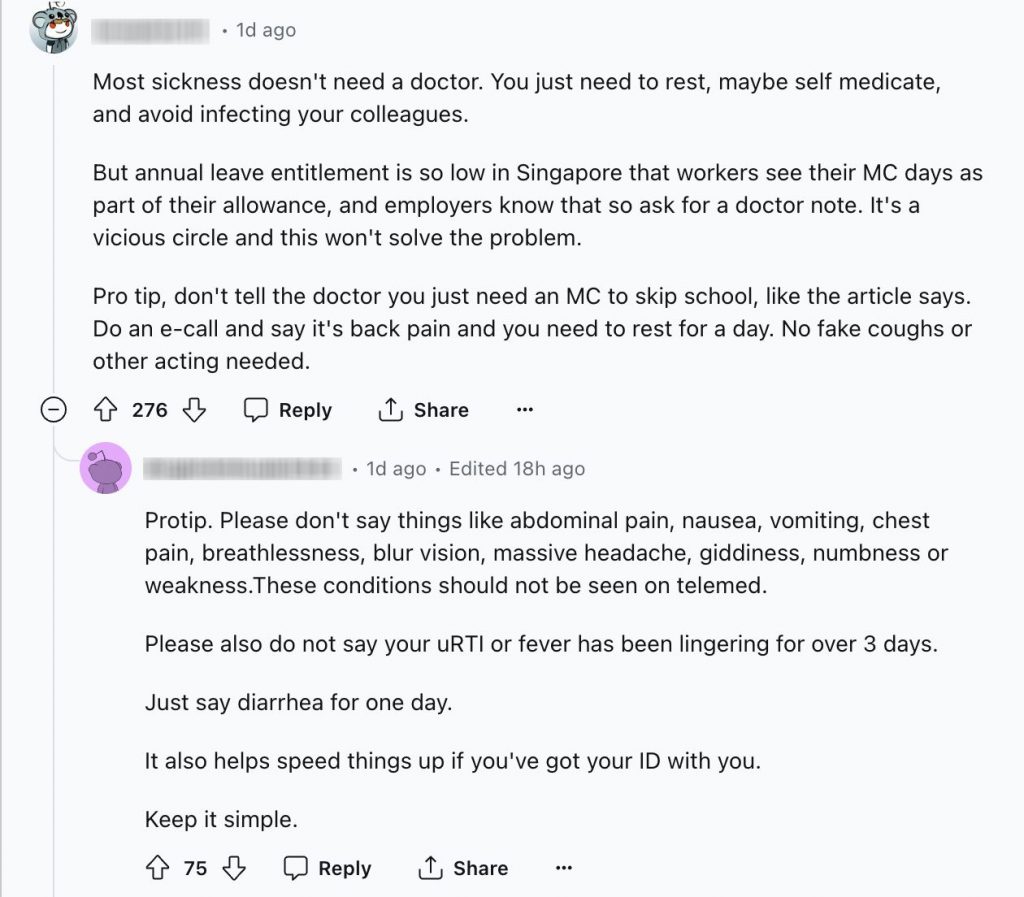

Just look at the reactions to MOH’s and SMC’s MC circular. You’ve already got Reddit threads of people discussing how to game the new system.

The reality is that there is such guilt and shame—some self-inflicted, some derived by demanding bosses—associated with taking time off from work that employees have to feign illness for a mental health break.

Some companies like Google have started introducing mental health days (the company calls these “reset days”) where employees can take a break without a medical certificate. But progressive policies like these are still few and far between.

Even if mental health days became more widespread, though, I’m not sure they’d take off here in Singapore. Asking for time off is already difficult for many.

“Taking leave for the purpose of taking a break from work may bring work to a standstill and leave employees worrying that their co-workers or managers will think negatively of them,” Chirag Agarwal, co-founder of counselling platform Talk Your Heart Out, tells The Straits Times.

“Some may even attribute taking leave as a personal weakness, as they feel that they are not capable enough to follow through with their tasks.”

It’s not a simple matter of generational differences. When local online media company SGAG introduced unlimited paid time off in 2015 to encourage work-life balance, the policy backfired. Employees ended up not utilising the perk as they were wary of giving their colleagues more work to shoulder, and didn’t want to appear like they were skiving. The company eventually scrapped unlimited leave and went back to the conventional 21-day arrangement.

Cutting Workers Some Slack

When the average worker feels overwhelmed, the best option seems to be to call in sick. After all, who can blame you for falling ill? It’s almost like there’s less culpability because falling sick is something out of one’s control. Taking a mental health day might be viewed as selfish while the rest of the team trucks on. Taking a sick day leaves less room for arrows in the workplace.

Maybe the solution, counterintuitive as it may be, is to reduce the policing of sick leave. Accept the fact that employees might occasionally need a sick day off—or a mental health day—and that you can still trust them to do their jobs.

With the government’s push to get more companies to consider flexible work arrangements, maybe we’re entering an era where medical leave policies don’t have to be so rigid. For example, let someone who’s not well enough to make the trip to the office do work and take meetings remotely from home instead. Let the person take it slow and have the expectation that they might not be as quickly responsive.

As much as employers might think loosening sick leave requirements might result in an empty office and zero work done, people are generally prudent and don’t want to stand out for the wrong reasons in their workplace. Treat people like adults and they’ll behave like adults too.

Even in the absence of hard and fast quotas, the natural instinct is to match the “market rate”. Research overseas shows that people tend to take less vacation days when given unlimited leave.

Instead of badgering doctors to stop giving out MCs so freely, maybe employers should focus on why employees feel the need to malinger in the first place. More often than not, they’ll find that it’s a problem of their own making.