In ‘Singaporeans Abroad’, we share with you the stories of locals who—thanks to living in a globalised world—have found success in different corners of the globe, whether financially, romantically, or for the pure joy of adventure.

We recently heard from Bella Lee, a social work graduate who chose a job counselling orphans in Thailand for no pay. Then, there was Fabian Low, whose search for a sense of self led him to a tiny house in New Zealand.

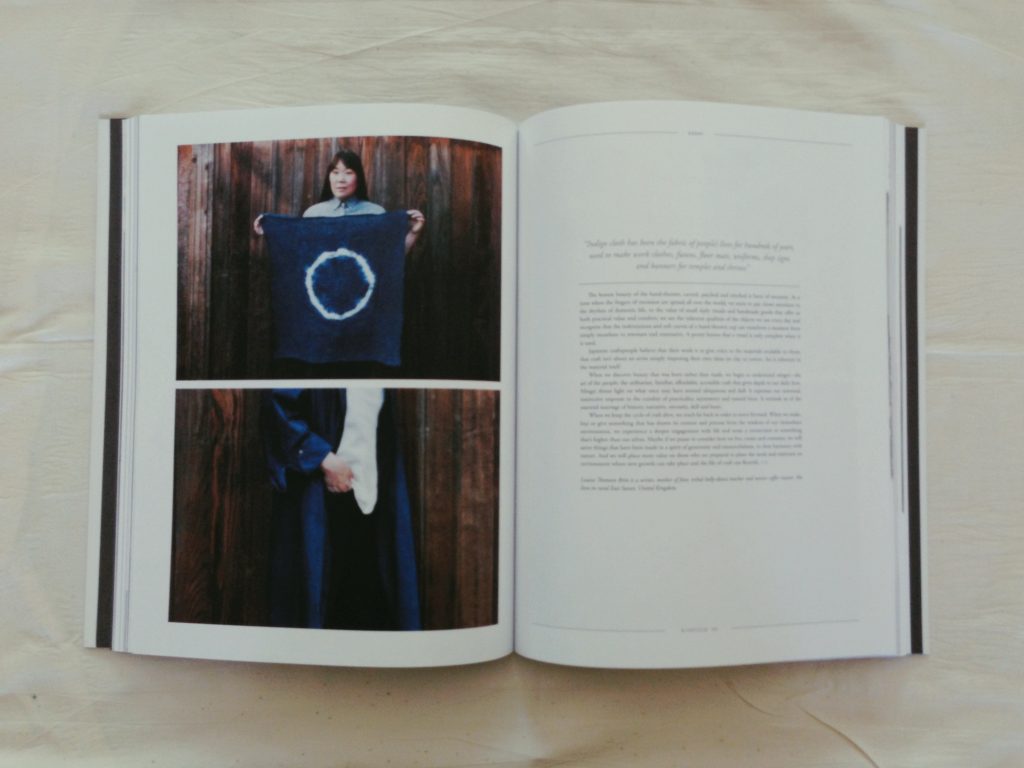

Now, we bring you Felix Nai, a Singaporean whose fascination with indigo farming and indigo artistry led him to study this art form in Japan for two years. He has since come back to Singapore to create and teach indigo art. Felix is usually seen as the man with the blue fingertips, a result of his dedication to his inky craft.

All photos by Stephanie Lee for RICE Media unless otherwise stated.

Mesmerised by Indigo

People who see my nails think I’ve had a manicure. But I see my blue nails as my name card. It’s a conversation starter, for sure, plus my hands are blue up to my forearms.

I always get stares, and some people think I’m sick or got tattooed. I don’t see these as sacrifices though. I could easily just take on another job that pays well, but I choose to help keep this craft of indigo dyeing alive.

But let me introduce myself for a bit.

I graduated in 2013 with a Diploma in Apparel Design & Merchandising at age 20. I took it up at Temasek Polytechnic. That same year, I also made it to the finals of Audi Star Creations, a competition for upstart fashion designers from across Asia.

During my final year project, I spent so much time thinking about clothes and fashion. The one module which was the most memorable was textile manipulation, which is not taught anymore. It was a module where we learned about different dyeing techniques, batik and screen printing. We dealt with chemical dyes back then.

I recall myself thinking that it would be great if we were exposed to natural dyes back then during this module. This was also the reason why I went back to teach and hopefully be able to advocate natural dyes.

I had witnessed the damage that bleach dyeing can do to human hands. I cannot imagine how much damage it can do on nature, in large amounts, and so I decided not to practice that anymore.

However, at the end of the day, most consumers just want a straightforward product. The process of creating consumer goods these days is often overlooked and discounted. I sought something more meaningful, which would last for a longer period of time.

My budding fascination with indigo started with a magazine article I chanced upon one day. The images reminded me of a beautiful night sky I once saw in Germany.

Back then, I asked myself if it might be possible to recreate this celestial vista with human hands. This led me to attend a workshop held in Singapore by a traditional Japanese craftsman.

However, if I wanted to pursue this seriously, I needed money to travel. I signed up to be a flight steward with Singapore Airlines, during which I made several trips to Japan and honed my proficiency in Japanese.

During this time, I kept up my friendship with the Japanese craftsman. In 2018, I popped the question: I asked if I could be an apprentice in the craftsman’s facility in Tokushima. It’s one of the only places on earth where high-quality indigo can be grown.

My request was accepted. Thus began my foray into the art of indigo.

From Student to Artisan

I had mentioned this opportunity to study indigo farming and dyeing to my former lecturer and course manager, who gave me encouragement to pursue this apprenticeship in Japan. I started becoming fluent in Japanese.

Not all Japanese people close themselves off to foreigners. My time as a cabin crew helped me understand Japanese people’s culture. In fact, many of them are very open to sharing, because this new generation of entrepreneurs is very open to introducing their craft to the rest of the world.

In Japan, I felt a community spirit without much resistance to a foreigner learning their art. They keep their art form pure without excluding outsiders. So, in turn, I helped connect these artisans with more people.

First off, what is indigo? Many people know it as the colour of their jeans, but my apprenticeship drew me into a deep relationship and understanding with this plant, dye, colour and art form. I studied under a master and a grandmaster–the latter, in his 70s, who is the seventh generation of an indigo farming and dyeing family.

When I want to initiate a conversation with people in Singapore, yes, I talk about the indigo shade of blue jeans. But, for me, I had the privilege of seeing the world through the lens of indigo.

From the growing of the indigo plant to the treating of its soil, I started to look at the broader spectrum. We use other ingredients like wood ash–trash to some, but valuable to our craft.

Natural indigo is well-known across Japan, but younger folk perceive it as a mom-and-pop craft. It is becoming more scarce–master indigo farmers are getting on in their years and climate change has been affecting the quality and quantity of the crops. There is a cap to our yearly yield. The waiting list for indigo-dyed products, on the other hand, continues to grow longer.

Indigo is touted to be anti-bacterial and flame retardant, with antioxidant qualities to boot. However, the veracity of these traits has not yet been extensively researched. And, as soil properties and climate conditions worsen, the indigo reaped strays further from these qualities. Nonetheless, we soldier on to produce the best indigo products that we can.

Blue pigments found in nature are usually insoluble. This is why fermentation is needed to break down the compound before it can be used as a dye. Yes, soluble blue can be extracted from a source like the blue pea flower, but this form of dye is unable to permanently dye a fabric. We are transparent with our processes, so that people know how much effort goes into the products that they hold in their hands.

Felix outlines the process of indigo dyeing for us in his current Singapore studio.

Step 1: “Submerge the fabric into the dye.”

Step 2 (pictured left): “Wring to remove any pockets of air within.”

Step 3 (pictured right): “Open up the fabric item to expose all parts of the dye.”

Step 4 (right): “Consolidate, bring it out of the dye and wring the fabric.”

Step 5: Open up the fabric to allow oxidation to happen.

In Deep with Indigo

This labour of love begins with cultivating the soil and plants, harvesting them and composting their leaves, which takes about a year.

For me, the most tedious process is preparing for a simple workshop.

The indigo required takes me at least one year and two weeks to prepare. Farming is a year-long process and its growing and composting techniques are very labour-intensive. Real estate is another limiting factor because a large land area is required to grow a substantial number of leaves that contain the prized indigo molecule. My favourite part is extracting the colours.

It’s like a pregnancy, with different phases that you have to monitor. It takes time to ‘grow’ the colours and ferment the bacteria in favourable conditions, like optimal temperature and the right pH value.

I name all my indigo vats because they have different ‘personalities’. Some vats can function a lot better when interacting a lot with people—I call them ‘extroverted’, while some vats need to be left alone in order to develop well.

My workshops’ participants get to understand this concept that, in nature, if something doesn’t happen, it doesn’t happen. It can give me anxiety, but I choose to believe that this has amplified this belief of mine and I am a more spiritual person now.

Indigo dye can achieve a wide array of shades, which is derived from the different things artisans do to their different batches of indigo. Indigo agriculture and artistry is like making kombucha—different people have different practices and recipes.

My learning experience as a journeyman in Tokushima, Japan lasted three years, and would have continued if not for COVID lockdown-related travel restrictions imposed in 2020. COVID served as a fork in the road for me.

Instead of choosing to stay in Japan and be closed off from my family and friends in Singapore, I opted to return home to share the skills and knowledge that I had received.

Indigo as Medium

I learned a lot about how to manipulate fabrics in Temasek Polytechnic, which served as a great starting point. I would otherwise not have been able to understand or grasp new techniques. This allowed me to focus on translating these ideas into designs.

Until today, I have kept in contact with my lecturers and visit Temasek Polytechnic every now and then to check out new developments and to pick my former lecturers’ brains.

Temasek Polytechnic also welcomed me back as an adjunct lecturer of indigo artistry. I am grateful for the opportunities afforded to me and like sharing my craft with Temasek Polytechnic students.

I enjoy introducing indigo to students to gear them up for the future and expose them to more topics, so that they will not feel like they have been thrown into the deep end when they enter the working world.

Instead of focusing on creating new crafts with indigo dye, I founded Good Riddance, which instead shines the spotlight on indigo as a repair medium–one that can dye over fabric and give them a new lease of life.

With COVID having had Singaporeans indoors, preventing them from travelling during the Circuit Breaker phases, it resulted in surging interest in indigo dyeing. Organisations reached out to me, which led to Good Riddance quickly developing into a sustainable business.

With Good Riddance, I hope to do more than simply working with indigo. However, I am in no rush to scale up. I don’t wish to squeeze this craft dry for the sake of business. Indigo is a medium and a conversation starter, and I try to delve into broader subjects–like biomaterials, natural pigments and fermenting bacteria–in my workshops.

In Tokushima, I lived in a zero-waste town called Kamikatsu. This town enjoyed a rich spirit of community. So, when I returned to Singapore, the first thing I wanted to do was share my experiences and these ideas surrounding sustainability.

I don’t try to bring across a message, but convey a feeling, because a feeling will last longer. I would like others to constantly make a conscious decision, as they consume in their daily lives. Like things that we eat and drink, each has a story behind it.

What we do might never be 100 per cent sustainable. But if I can change mindsets and encourage others to think about what they consume, then I have done my job.