All photos by Stephanie Lee for RICE Media.

This is the story of Aaron, 60, who first fell into drug addiction at the young age of 15. Over the next two decades, he endured five jail sentences and lost his right leg to cancer. Today, he tells his story in his own words, which has been edited and rewritten for clarity.

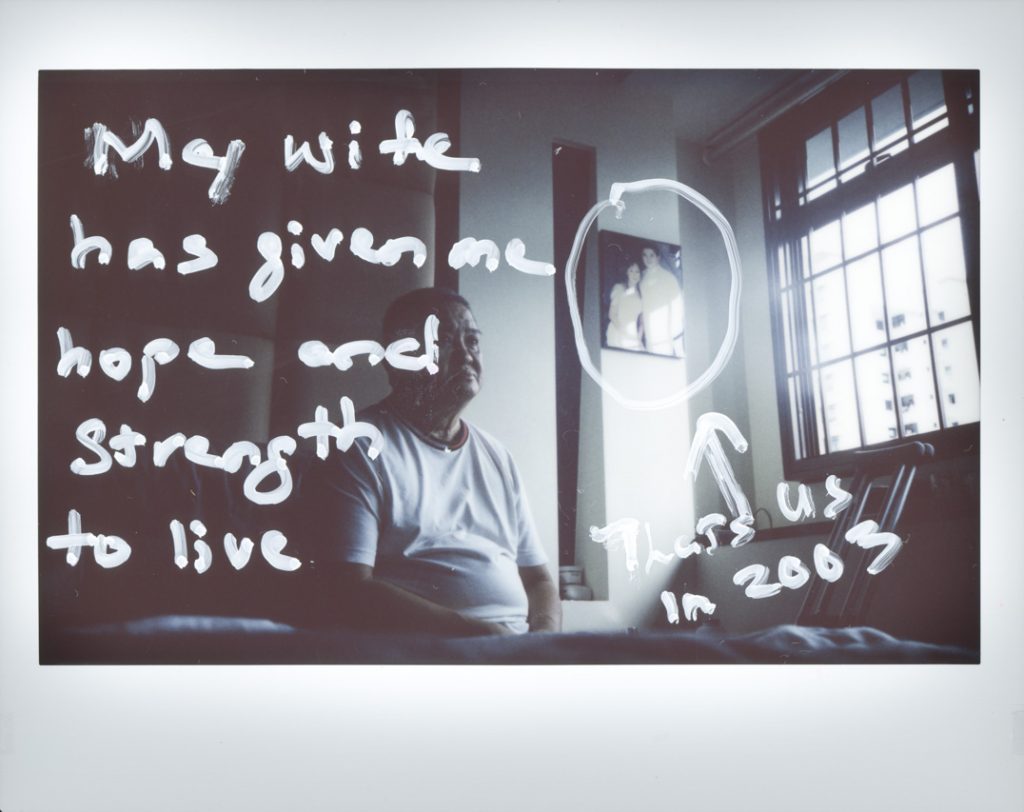

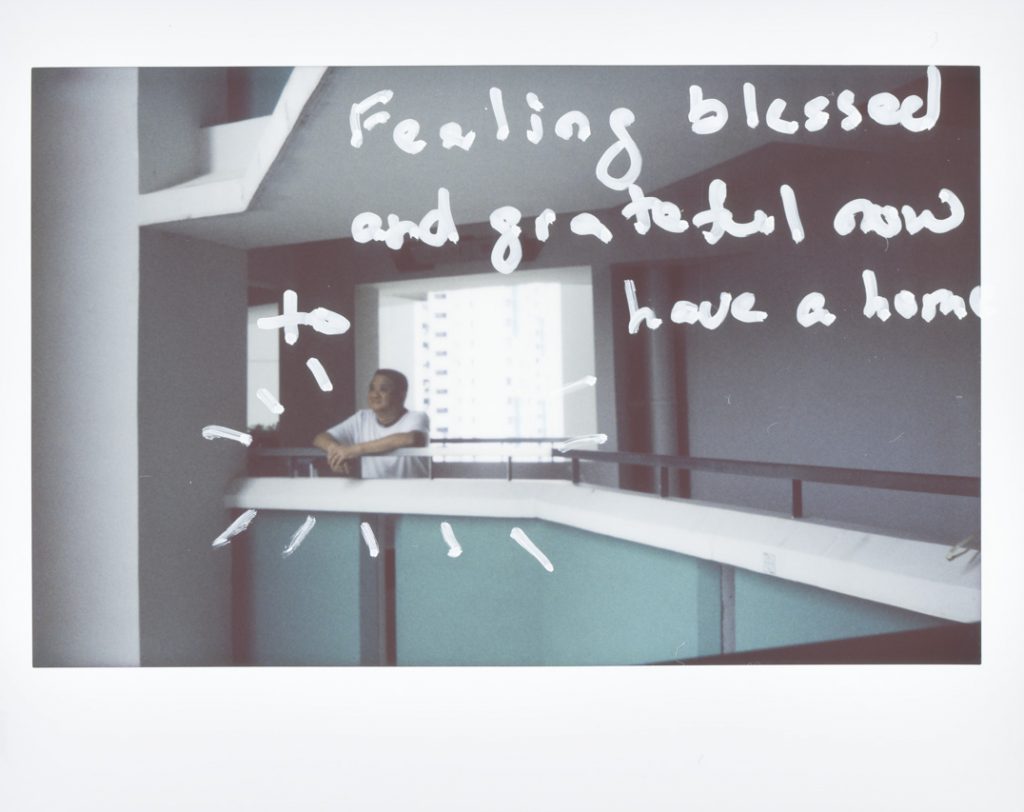

This article is accompanied by polaroids taken by our photographer, with notes handwritten by Aaron himself.

I was 15 when my father reported me to CNB (Central Narcotics Bureau).

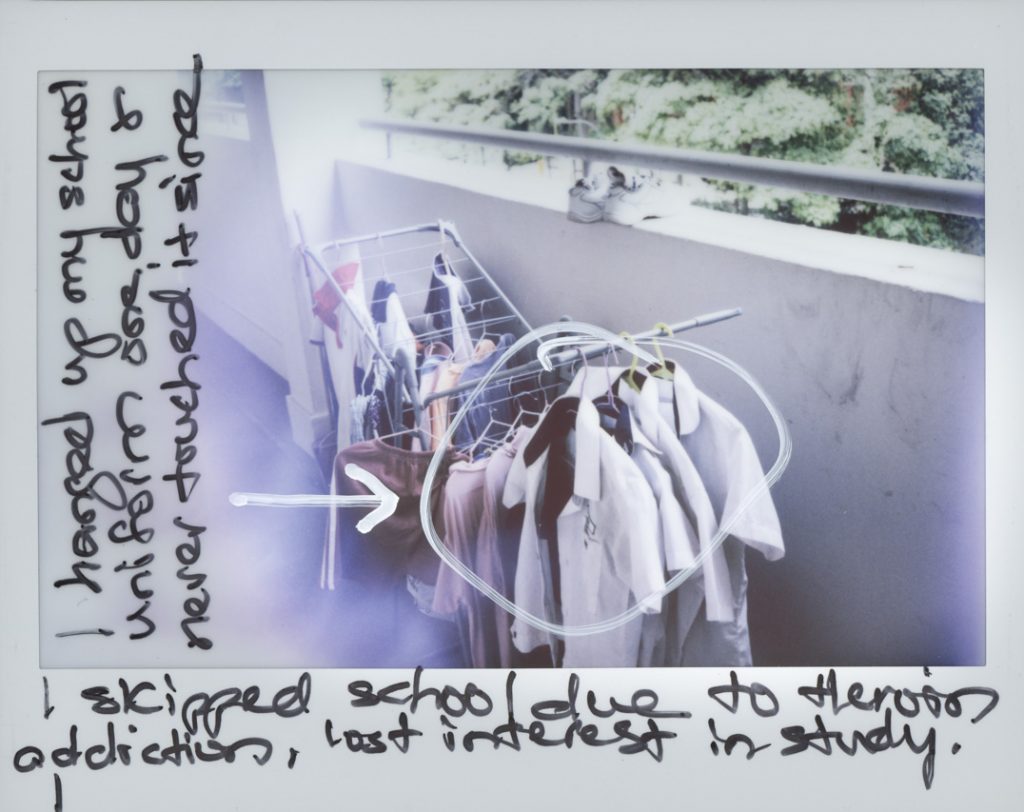

It happened one morning, sometime in 1976 or 1977. I cannot remember the exact date. While most of my friends were attending school, I stayed at my neighbour’s home. Ponteng, lah, as we used to call it. I ponteng (skipped) school for months.

There was a knock at my door, and I let the CNB officers in.

I didn’t say anything. I knew what was happening. She just watched me as I stepped out into the living room in handcuffs, being led to someplace far away from my home. I was getting detained for drug use—the only thing in my life that didn’t make me feel so hopeless.

My father didn’t see me go. He barely talked to me at all. It was mostly silence from him.

When he called CNB to take me, it felt like he finally admitted I was beyond his control. I still don’t know if he told them to come “take my son” or if I was treated as a pest being chased out of the house.

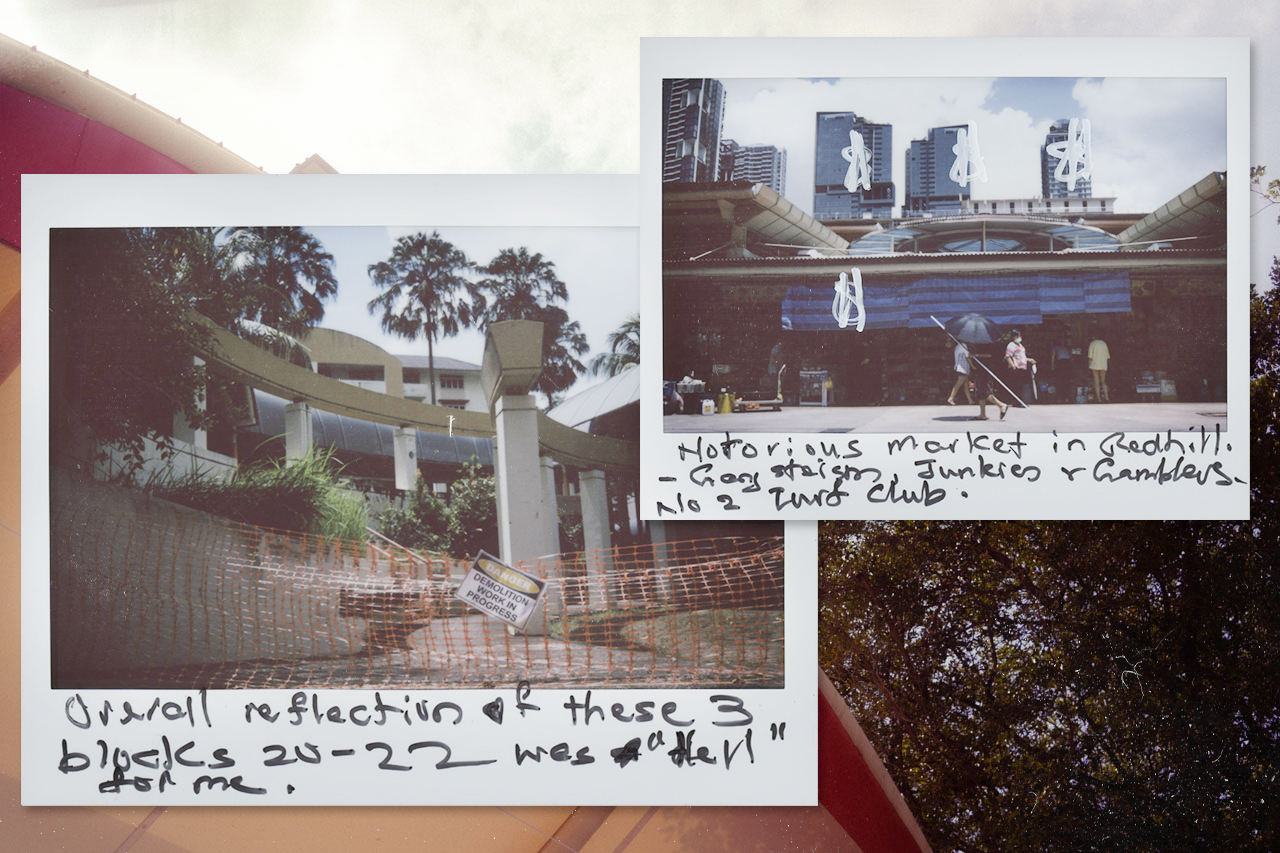

In the 1970s, I lived in Redhill Close, along Jalan Bukit Merah. Back then, I bumped into drug dealers at the hawker market. I saw middle-aged men, high on opium, idling at the coffee stalls. I watched gamblers playing dice and matchsticks. I witnessed all the gang fights.

Dealers mainly sold heroin. It was a powdery substance contained in a straw.

They used to lace cigarettes with it. The first time I saw one, I laughed. I took out a stick from the pack of Dunhills I stashed in my school uniform and looked at them side by side. They looked the same.

Idle Mind, Nevermind

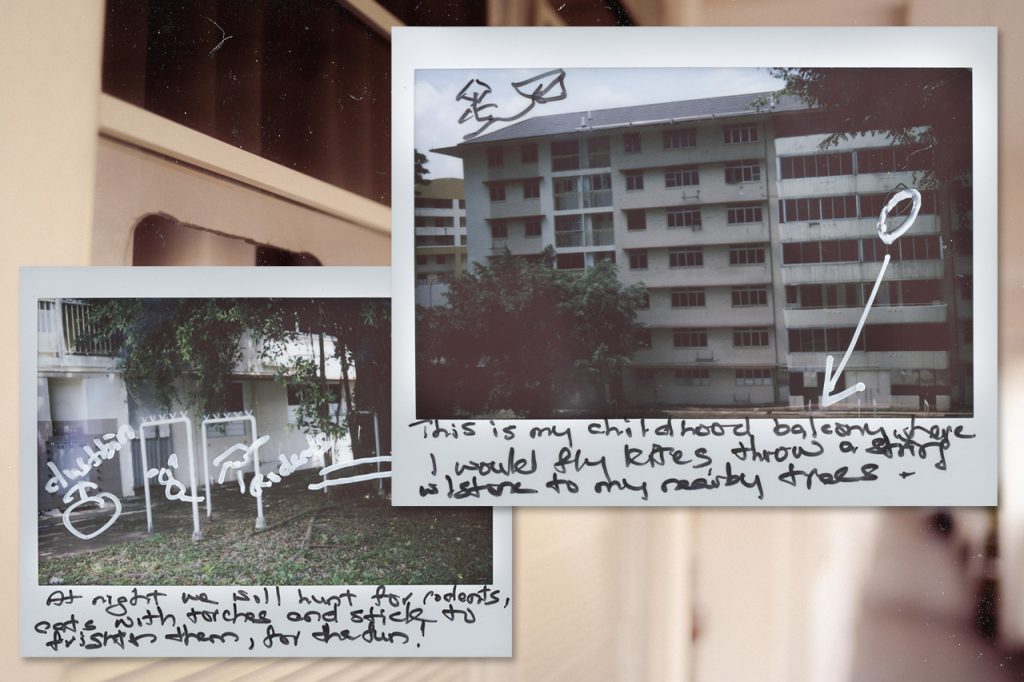

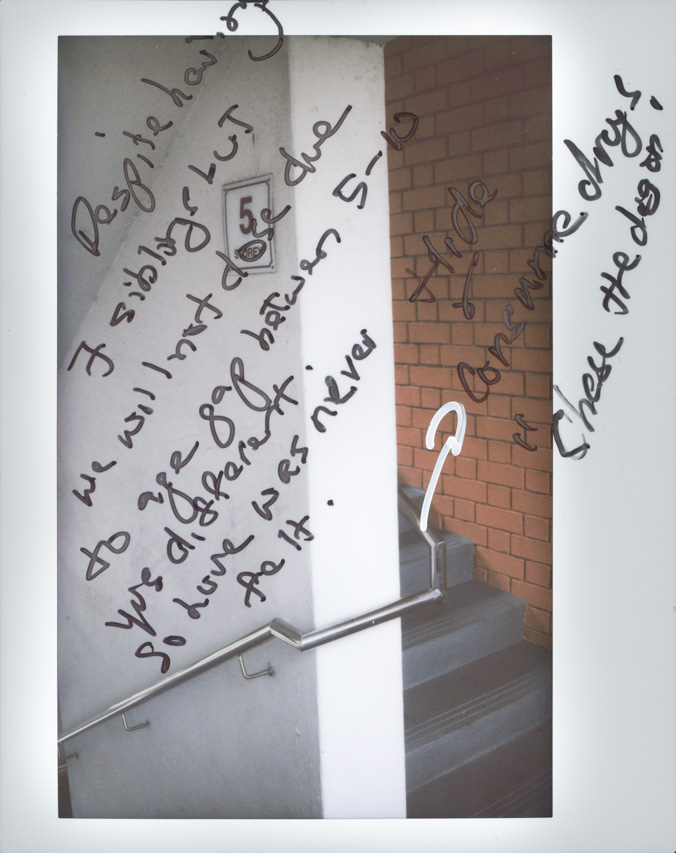

There wasn’t much to do after school. Whenever I came back home, my older siblings (all six of them) would keep to themselves or stay out of the house. I was the youngest child—they saw me as the pampered one.

At night, we would all squeeze into our small two-room flat to catch some sleep. Over time, less and less people slept in the room with me. Most got married and moved out. My parents barely talked to me. Only my friends downstairs would.

We smoked cigarettes together. We would always share sticks. One of them was my neighbour from the opposite block. He was older, about 30 plus. I can still recall what most of them looked like, but I remember him the most.

They would talk about “chasing the dragon” (slang for chasing a drug-fueled high). One afternoon, they finally did it. My neighbour took out a small straw of the powdery substance I saw at Redhill Market. He would carefully drop some of the substance onto the foil from the cigarette pack, light it with a lighter, and inhaled the smoke through a rolled-up dollar note.

I didn’t know what “dragon” they were talking about. I only wanted to smoke.

The feeling when you first try heroin is something I cannot describe. It felt like I was in heaven. I felt so alone at the time that I was happy there was something that finally took my pain away from me. But that only lasted for a short time.

Every single time, I would be dragged back to reality. It frustrated me. It made me angrier. I wanted to go back. This dragon was very strong.

I stopped going to school. I continued my chase. It was all I wanted to do every day. The money I got selling newspapers and snacks meant that I didn’t always rely on my friends for a free fix. My parents didn’t question why I stayed at home. They would just look at me when I returned home each night, resigned, their faces very sian.

I understand now what I went through for most of my life. I became addicted not because I was “stubborn”, “useless”, or whatever my siblings would call me.

To understand addiction—and overcoming it—isn’t to talk about stubbornness or laziness. Those who have never gone through it will simply never understand. This is why I want to talk about it.

First, it was the laced cigarettes. Then, MX (methaqualone) pills. The “dragon” became more lifelike with cannabis. It was no friend to me. Then again, I don’t think I had any friends.

A Hallway for a Cell Room

I heard it was the biggest drug bust in Singapore. Whispers went around in our tiny cell—no bigger than a two-room HDB unit—among other men who, like me, failed their urine test. We shared one toilet. We rationed one soap bar for our daily showers. We shared the pain of being alone together without speaking.

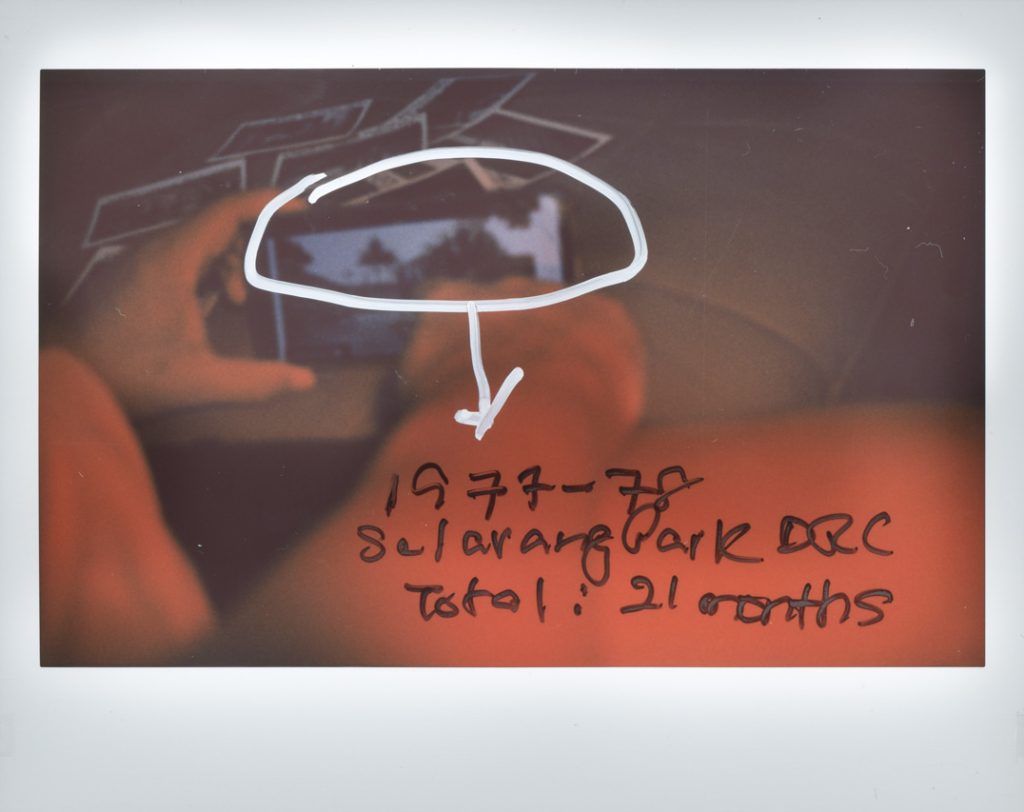

This was in Telok Paku Drug Rehabilitation Centre (DRC), somewhere in Changi. In a crowded cell, my kakis were nowhere to be found. Just shivering bodies, all 44 of them. About two months later, we moved down the road to Selarang Park DRC. That place was much bigger.

There were no drugs to ease our pain, so some of us took it out on each other. I wasn’t strong at all to throw a punch. That didn’t matter whenever the wardens forced us to crawl, on our hands and feet, up a slope every day.

I was only a kid. I got in here because I needed something, anything, to take my suffering away. I couldn’t give a damn what would happen to me after this.

When I got out in May 1978, I didn’t know where to go—except look for another fix. Two weeks later, I was back inside. I served 15 months.

This time, I was inside for much longer. At least I wasn’t asked to hurt other people or myself. We played basketball. We smuggled cigarettes. We got to see our loved ones. My mother brought biscuits that tasted better than anything we served inside. My sister gave me a book: How to Stop Worrying and Start Living. That one wasn’t much help.

But, you know what? When I got out, I felt like I could do something. I got my first full-time job as a waiter in a hotel. I met new people who played bowling in their free time. And yet, the urge was there. I just had cigarettes to swat the dragon away. It didn’t last long.

Not when I got called to serve the nation.

Hormat

There was a lump on my right leg, bulbous but benign. When I was an 18-year-old recruit, I was declared unfit for most exercises. I had nothing to do in my bunk. Then, I started talking to my platoon mates. I found out some of them smuggled drugs into camp. So free inside, what else could I do? I took some. And then I started dealing.

My addiction came back, and it was stronger. It was harder to deal with it. For every 10 straws I sold, I kept two for myself. We went through our usual urine test. I fled before they could get my results. They call it AWOL.

I hid at home. My parents didn’t blink an eye when they saw me stay at home all week. It took a month until the military police came to my house to retrieve me. I had no energy, nor the right mind, to run anymore.

To my parents, the third time didn’t matter. They thought I was hopeless. It’s okay, I thought the same thing. I stole from my mother, I lied to my friends—just for a quick escape within my head. I spent countless hours strung out on my bed.

Prison felt like the only way I could get away from all my problems. Over there, my mother’s purse was out of reach.

In the military detention barracks, we marched long distances with heavy sandbags strapped onto our backs. My lump began acting up. The medical officer sent me to Changi Hospital. The doctors brushed off my concerns, but I pressed them to let me stay in the hospital—anywhere but the detention barracks. They agreed, as long as I was handcuffed to my bed whenever I was left alone.

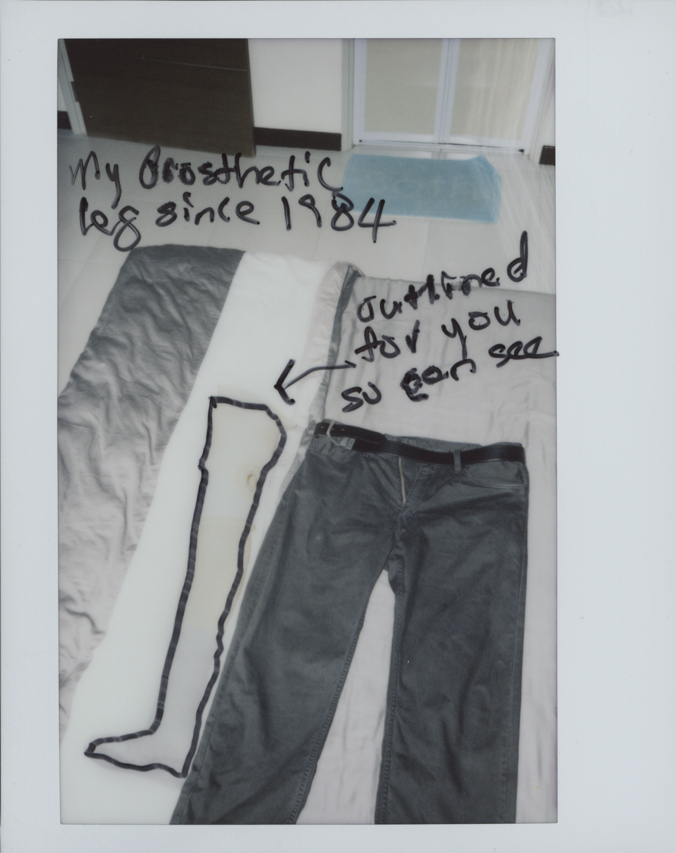

Two weeks into my hospital stay, my doctor informed me that the lump is cancerous. “We can remove it. But…” he paused.

“It also means your whole leg will be gone.”

My detention officer visited the day after. He looked weary and sad—very unlike him since this was the man we feared most in the barracks. He instructed the military police to remove my handcuffs. Then, he asked how I was. Somehow, the man who slapped and punished inmates became someone who cared about me the most.

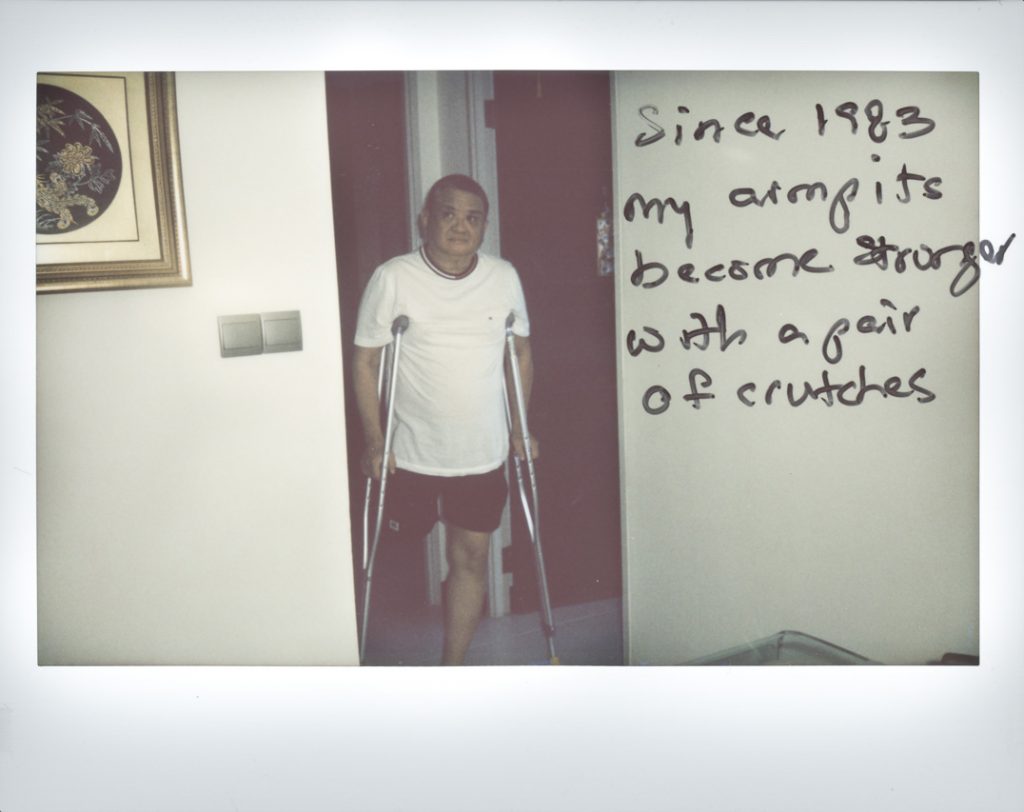

He approved my discharge. I was given a lease of life I wasn’t sure I wanted. I knew that drugs were not something I wanted to fall into again, but the pain that came after surgery was too much to bear. I later learned it’s called “phantom pain”.

The best pain relief? Morphine.

I didn’t get it from the hospital. Their painkillers didn’t help much. I begged my former supplier for some doses as I struggled with sharp pains down where my right leg used to be. This lasted for two years until officers came knocking on my door again. This time, my father was there to see me off.

No Halfway Route

I wish I could tell you I finally cleaned up my act by then. That I served my sentence, turned a whole new leaf and found the will to be a productive and positive person.

That’s what most people understand about former addicts. But the journey to get where I am today? I stumbled a lot along the way. I kept wondering why I was doing all of this.

After my first jail stint as an amputee, I went back to pushing drugs to cover my fix. I needed the money, and I didn’t know what else to do. From the years of 1977 to 1988, I was in and out of prison. I passed my O levels in my last stint.

Every day, even when things were going well, I lived fearing the next urine test. The stress got too much. I entered a halfway house in 1988. No halfway effort here, I swear.

I could still smoke outside the house. Every puff reminded me of how good heroin made me feel. My phantom pain still haunts me, but over the years, it became a part of me. It didn’t destroy me. Cigarettes became too painful to smoke without awakening the urge. Slowly, I got rid of that too.

How did I do it? To this day, it’s hard for me to put it into words. I didn’t just decide to drop it. I tried and tried. I kept trying until I found it easier to live my life without a puff.

My daughter is now 18. She’s in a polytechnic now. Over the last decade, I’ve watched her grow. When she was small, she asked me about everything. I told her all I know.

I’ve also told her about my past. That I spent my life up until my 30s lost and afraid. I told her about the drugs I found near my block. I tell her daddy is now round and plump because drugs made me too skinny.

If anyone were to ask me about my past, I would first offer them a packet of chrysanthemum tea. My story is long, but I will tell anyone if it means saving another life from the allure of drugs. If there are other people like me, I hope you can speak out before it’s too late.

Recovering over a long period doesn’t mean your life magically becomes better. It’s a slow, painful process that still goes on and on. I took my time to rebuild my relationship with my mum and dad.

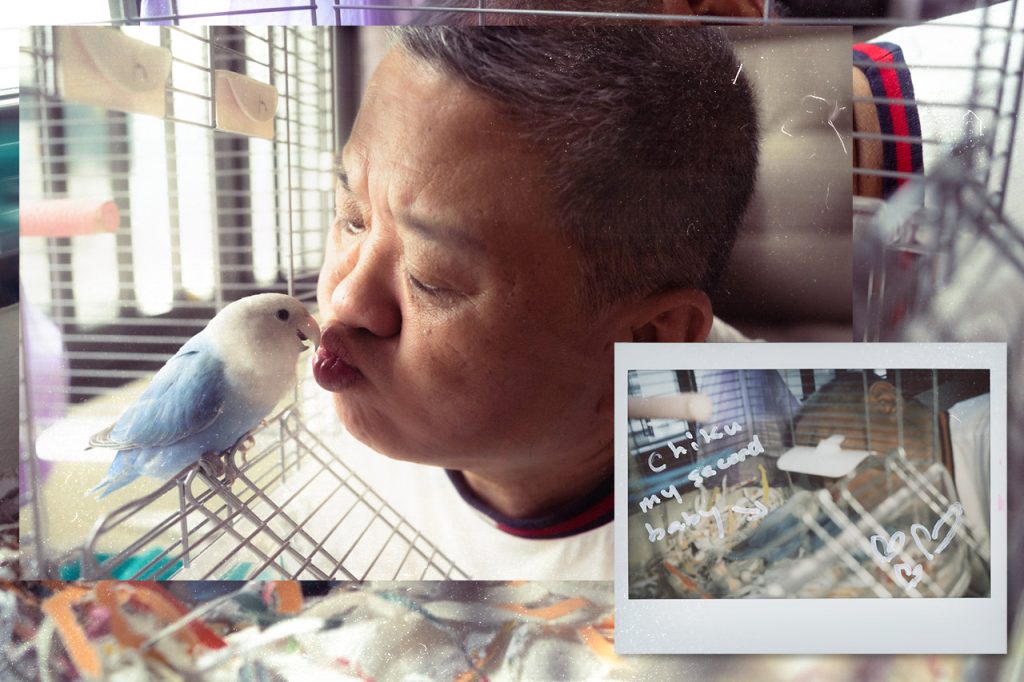

Now, with a family (including my dear bird Chiku) and a house to my name, I don’t need a stick to escape my life.

At 60, it’s just starting to get good.