Top Image: Stephanie Lee / RICE File Photo

Among the many constants in life: Death, taxes, and the recurring question of whether the People’s Association (PA) is politically neutral.

The PA’s purpose—to act as a bridge between the government and the people—shines with high-minded, altruistic, and apolitical purposes. “To Build and to Bridge communities in achieving One People, One Singapore,” its mission statement reads.

Among its many responsibilities, the PA manages the country’s 108 community clubs and grassroots organisations. As a statutory board, it also acts as a supportive messenger for the elected government of the day to explain and implement key policies and programmes. A little like the organisational equivalent of Hermes.

On the lighter side, the PA organises activities for Singaporeans to “develop friendships around common interests” and to connect “groups with different interests and backgrounds”.

Despite being politically neutral, the PA frequently finds itself in the middle of political debates. Most recently, it was raised in a parliamentary debate on 21 April. Minister for Culture, Community, and Youth Edwin Tong clarified in a written reply that the PA does not conduct activities with any political party.

He was responding to a question posed by Opposition MP He Ting Ru about how the interactions between politicians, grassroots, and the PA in outreach efforts were regulated.

Despite playing the Swiss neutrality card, the People’s Association finds itself (yet again) questioned about political affiliations. This raises the question: Why are we still debating the PA’s political affinities when the government has long assured us of its apolitical bearing?

The Everyday Singaporean Disagrees

Perhaps this is the reason: Singaporeans observe and feel that Opposition MPs face larger hurdles when trying to fulfil their duties as representatives of their constituents.

In 2020, netizens questioned why Opposition MP Jamus Lim was absent from officiating a community garden project in Sengkang West. Grassroots adviser Dr Lam Pin Min, a People’s Action Party (PAP) member, graced the opening instead.

Dr Lam Pin Min was most recently the MP for Sengkang West SMC from 2011 to 2020. Before that, Dr Lam was part of Ang Mo Kio GRC (Sengkang West) from 2006 to 2011. He was part of the team that lost the election to the Workers’ Party in 2020 in the newly formed Sengkang GRC.

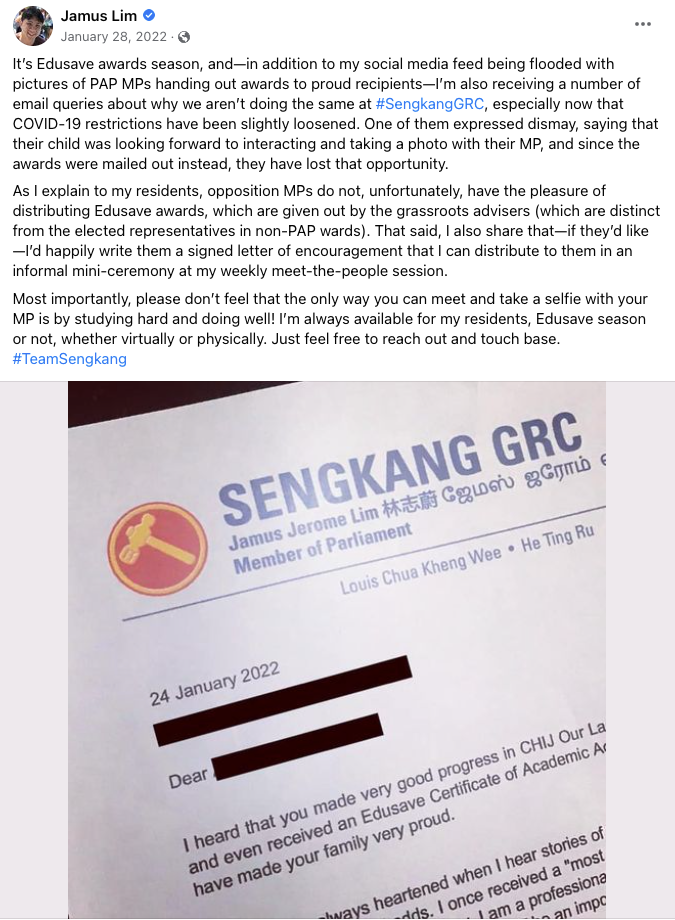

More recently, Opposition MP Jamus Lim explained in a Facebook post last year that he did not have the opportunity to distribute Edusave awards because it was grassroots advisers who did so.

The PA appoints these grassroots advisers to engage the public on government policies and schemes—its winged sandals, to take the Hermes analogy further. These advisers walk the ground, organise community events, and even have a say regarding improvement projects in residential estates.

In opposition wards, it’s possible for a PAP candidate to be appointed as a grassroots adviser to the same constituency they contested in.

The result is a strong PAP presence that elected opposition MPs have to “contend with”, as former Hougang SMC MP Png Eng Huat said in a 2020 Facebook post. Png also asserted this was a means of ensuring the losing PAP candidates would remain “relevant and visible” despite not being elected, illustrating his frustrations with several official letters from government bodies mistakenly addressing the estate’s grassroots adviser, Lee Hong Chuang, as MP.

Allowing Opposition MPs to take up grassroots adviser roles seems like the straightforward solution, especially if PA is non-partisan as it claims. But the association has long said that advisers are expected to champion government policies and that opposition MPs “cannot be expected to do this”.

“People who implement and operationalise these policies cannot oppose them,” PAP MP Dr Janil Puthucheary told Yahoo News way back in 2011. “You simply can’t have a situation where the adviser does not support the implementation of these policies.”

Given that elected Opposition MPs do form part of the government, is it fair to say that PA is a completely apolitical organisation?

If anything, the PA’s stance only blurs the line between government and political party. It doesn’t do the claims of non-partisanship any favours.

The People’s Association, Borne Out of Turmoil

Even if the PA doesn’t conduct activities with any political party, its beginnings are surely political. The organisation was founded on 1 July 1960 to unite once disparate segments of society and to plaster the gaping cracks between Singapore’s different racial and religious groups.

Its inception was a response to the economic uncertainty and racial riots that characterised much of the 1950s and 1960s in Singapore.

As explained by Associate Professor Bilveer Singh in his landmark textbook Understanding Singapore Politics, the People’s Association took on a secondary role right before Singapore gained its independence.

The first 28 community centres, originally set up by the colonial government, were taken over by the PA. Besides organising community activities for social cohesion, these centres—particularly the ones in rural areas—became hubs to gather feedback from citizens and relay key government messages.

After key members and community organisers split from the PAP and formed the Barisan Sosialis in 1961, the PA flew into action. 130 community centres were built in the single year of 1963.

According to Associate Professor Bilveer Singh, community centres, which were then already managed by the PA, took on a political role. Community centres transformed into hubs for “political mobilisation” to draw support, build partisan loyalty among residents, and consolidate political power.

Fast forward to the present day, and a cursory glance at the People’s Association Management Board will bring up a few notable faces—the majority of whom are from the PAP.

While the PA of today might not engage in political activities, at the very least, its history suggests that it can be used expediently as an instrument for political ends. It might not need to engage in activities with political parties, but it can be political.

Let’s Call a Spade a Spade

In theory, the People’s Association is a statutory board. People see it as a cog in a much larger and incredibly efficient bureaucratic structure known as the Civil Service. And much ideological work has been done to separate the Civil Service from the state’s political decision-making body.

In 2023, Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister Lawrence Wong made it clear that political decision-making bodies and civil servants need some separation—working in the public service requires political sensitivity, but the line is drawn at politicisation.

In a perfect world, the ideal bureaucrat is someone whose work is essentially lubricant to the large administrative machinery—papers are pushed, complaints are processed, and laws are executed. Higher-order decision-making is ideally left to the government of the day, representing the wants and needs of its citizens.

Even the values a civil servant should embody differ from that of a political decision-maker. In a country which prizes meritocracy, the perfect civil servant exudes neutral competence and rationality.

However, this separation between administrators and politicians is a confusing myth at best, at least to Singaporeans. The clear-cut division is easy to chew on but rarely do such situations play out in the real world.

This separation between politicians and administrators overshadows a more pertinent process: Policymaking versus policy implementation. And in Singapore, these two seem to go hand in hand.

It’s hard to exclude administrators from the policymaking process, especially when large decisions trickle down and affect how they interact with everyday Singaporeans.

From the Singaporean requesting another chance to buy a BTO flat to the one asking to withdraw their CPF funds early, civil servants exercise quick-time judgements not in the grand halls of Parliament, but in the drab cubicles of grey and overbearing offices. It’s a process known as administrative discretion.

Part of the reason the current government has been so rapidly successful is the complementary relationship between the two. Ultimately, Singapore owes much of its success because of this synchronicity. When the gears are inherently greased and oiled, the machine runs without a hitch.

It’s also precisely why the PA has been successful in its mission.

Doing vs Being

In the same vein, administrators should be insulated from the pressures of partisan politics. In fact, not engaging in activities with political parties is healthy for the overarching political system.

Yet, the PA’s inherent reason for existence is entangled with partisan politics. And until it can fully rid itself of these entanglements, it will continue to be embroiled in political debates.

Debating, however, misses the point. The fact is that some of the policies involving the PA affect the bread-and-butter of politicians: Engaging with their constituents on the ground. Some politicians just have it a lot easier than others—an in-built imbalance that will be hard to shake off.

While the PA does not engage in activities of a political nature, its history and make-up show that it has the capacity to be political, even if unintended or implicit.

In no way, shape, or form does being political undermine the PA’s altruistic purpose of connecting Singaporeans from different socioeconomic backgrounds.

But let’s call a spade a spade. At its heart, the People’s Association is not apolitical, whether it intends to be or not.