All images by Stephanie Lee for RICE Media

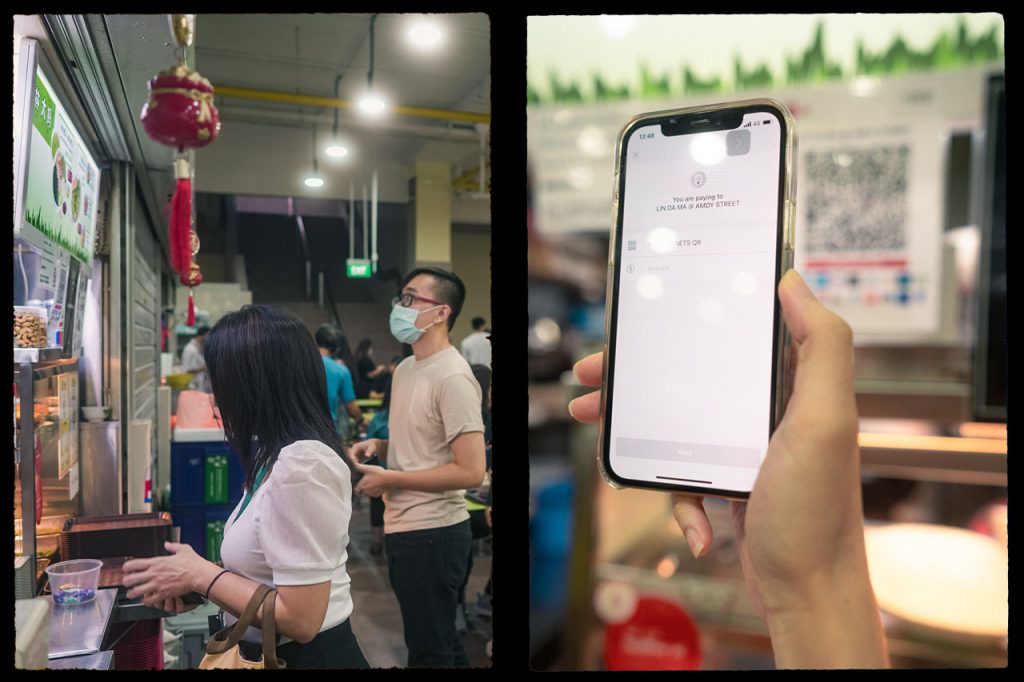

On the second level of CBD food haunt Amoy Street Food Centre, snaking queues often converge into a tricky mess during lunchtime.

As Singaporeans, our gospel truth is but one thing: A long queue means a certain hawker must have the best food. But while those popular hawkers are kept busy, what do their neighbours feel about the queues?

A Queue Before You

One such stall is Lin Da Ma Lei Cha. From where it’s located, sandwiched between two hawker powerhouses, it’s barely noticeable. Its bright chroma key green signboard is the only thing visible over its neighbours’ queues.

To the shop’s left is a fish soup stall with a queue that, at its peak, can stretch beyond an hour. To the right: another well-loved wanton noodle hawker with a queue that’s also long, just less dramatically so.

Mrs Lin Bee Lian, who is in her sixties, is the person behind Lin Da Ma Lei Cha. She decided to start the business nine years ago after noticing the lack of fresh greens in the general hawker scene.

Lei cha, a rice dish served with several sides of vegetables, tofu and nuts, is eaten with an earthy, aromatic thick tea soup. Due to the herbaceous nature of the tea soup (which can be an acquired taste), early customers needed a little persuasion to give Mrs Lin’s lei cha a shot.

“Lei cha itself wasn’t exactly widely embraced in Singapore, especially back when we first started,” she tells me in Mandarin. “We were concerned about the obstruction and lack of visibility during our early days.”

It seems like a valid concern that Mrs Lin might feel squeezed out between her two popular hawker neighbours. When I bring up the topic, she acknowledges the challenge a limited space presents.

The main issue for her is that, with the long queues of her neighbours, her own customers don’t have enough space to wait in line. There, fish soup aficionados form a conga line, while lei cha lovers circle a single table like an ouroboros. Getting to the stall itself involves lots of “excuse me”, “coming through”, and signalling body language to others that you aren’t trying to cut their queue.

There can be benefits to being positioned next to popular stalls—a guaranteed stream of potential customers will definitely notice the lesser-known stalls as they queue—but that is still outweighed by the problems that come with the queues themselves.

Even though Amoy Food Centre allocates six tenants per row, Mrs Lin only has the popular two as neighbours. She tells us that, over the years, many hawkers have tried to set up shop at one of the vacant units on her row. One of the previous tenants has moved down a couple of rows, while another has shifted directly opposite their old unit. The other hawkers? Shuttered and gone.

Mrs Lin, on the other hand, has braved it out. In the past, a few occasions saw Mrs Lin’s queue merging with her neighbour’s—the combination of a hot afternoon with hungry and confused customers, after all, can mean a special kind of hell.

She has since managed to prevent repeat incidents by optimising overall operations, including the kitchen’s workflow—a method, tricky as it is, that she has fine-tuned over the years.

Her past nine years have been spent forming solid relationships with customers, coming up with Singapore’s first and only lei cha cold noodles, and keeping up with cashless payments such as food delivery apps and SGQR codes.

The latter, which can be scanned by DBS PayLah! users for digital payments, is also part of the bank’s 5 Million Hawker Meals initiative. Since February this year, the first 100,000 diners who use their DBS PayLah! app to pay for their hawker meal every Friday can get up to $3 in subsidy for their meal.

While Mrs Lin doesn’t have the exact numbers, she knows that, on a usual day, she sells roughly 140 bowls of lei cha rice and noodles. But since the initiative kicked in, the queues have stretched longer on Fridays, accompanied by a rough 15 to 20 per cent increase in sales.

He Who Walks the Longest

Mrs Lin’s resilience has kept her business steadfast at Amoy. For 35-year-old hawker Thomas Koh, resilience meant seeing through the opening, closing and reopening of his business, all within a year.

He says: “It’s inevitable that wherever you go, competition is just part and parcel of being a hawker. Even if you’re not competing with the stall next door, you’re still competing with all the hawkers within the same hawker centre. You’re also competing with all the different eateries within the same area.”

Having cut his teeth at his family’s hawker stall—Michelin Bib Gourmand recipient Koh Brother Pig’s Organ Soup, which is stationed at Tiong Bahru Market—the third-generation successor began the shop’s expansion at Maxwell with three friends. The offshoot brand, The Pig Organ Soup, began operations in June 2022 but quietly shuttered in March earlier this year—a mere nine months later.

Like Lin Da Ma Lei Cha, The Pig Organ Soup had been flanked on both sides by long queues. Back then, Thomas estimated a modest sale of 100 bowls a day. It was not enough. For months they languished in the red, all whilst watching the bustling neighbouring stalls.

While he felt his neighbours’ long queues didn’t directly impact his business, the day-to-day work became demoralising as weeks passed. His friends called it quits in January, with a loss double that of their initial investments.

Thomas had initially thought to give the business three years before seeing a turnaround. Nevertheless, the closure of The Pig Organ Soup’s Maxwell outlet did little to dampen Thomas’ spirit—he’s since reopened in a coffee shop at Tampines 824, reverting to its original name.

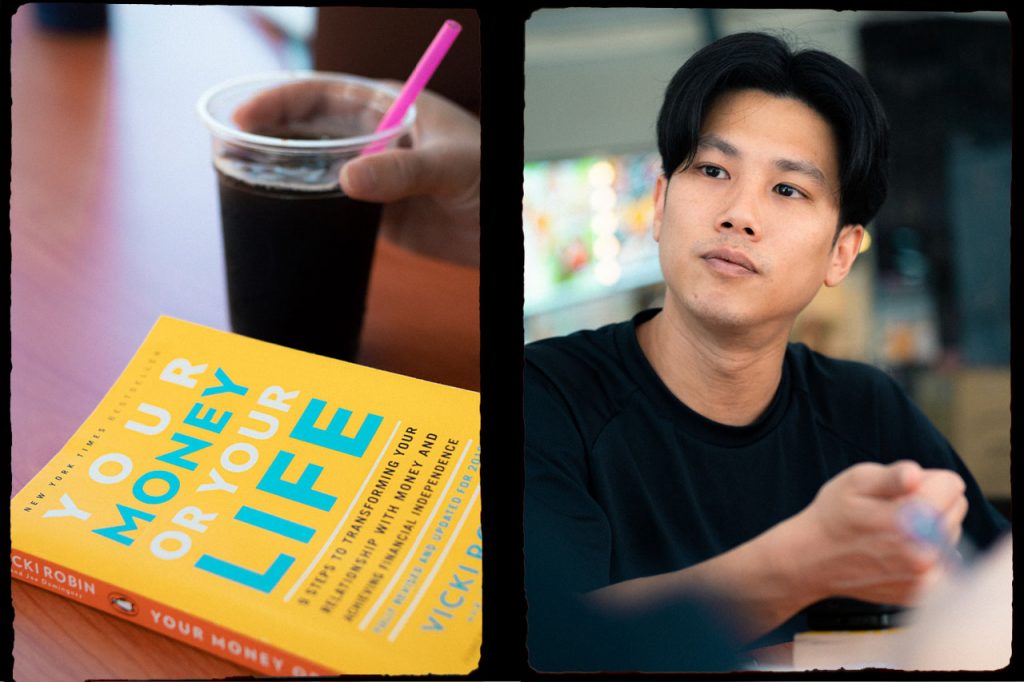

Armed with experience from Maxwell, and knowledge from a book he’s reading, the new stall is now inundated with orders from 1 PM. Notifications from food delivery apps ring off the hook. A queue now forms for him.

His advice? He says, with gravitas: “No matter what, if you keep walking, you’ll eventually get to where you want to be.”

It Is What You Make of It

High-visibility stalls can attract more business. Even then, that’s not all there is to it.

Location definitely matters, but not in the way one might think. From what I’ve witnessed, consumers naturally gravitate away from the shops closest to the toilets, in both small-scale hawker centres and coffee shops.

Support from partners can give businesses the push they need. The DBS PayLah! app has also been helpful, alongside the DBS 5 Million Hawker Meals initiative, Thomas attests.

He reports a 10 to 20 per cent increase in customers on Fridays, though his figures are limited to the original Koh Brother Pig’s Organ Soup at Tiong Bahru Market as he’s still sorting out the SGQR account for his new stall. Those making digital payments include elderly customers, mainly presumed as non-tech savvy. They line up in front of the stall with phones in hand, ready to scan the QR code with the DBS PayLah! app.

As with any business out there, what the hawkers do plays a large part in deciding whether they sink or swim. Mrs Lin’s son regularly checks out her stall to catch any signs of a budding problem or a potential opportunity. Their Lei Cha Cold Noodles started as a suggestion by Philip and his siblings, and it’s the first item that sells out every day at their Amoy branch.

For Thomas, it took a decisive shift for him to find his crowd, which, as he discovered, were specially travelling to the CBD just for his dishes. It helped that his earliest customers in Tampines recognised his family’s brand. “Trust is important,” he tells me. “If they don’t know us, they don’t know whether [the innards] we prepare are clean.” The word spread and the queue grew.

In an effort to maintain demand, he now offers braised dishes alongside the regular pig organ soup at his new stall—its taste balanced just enough not to overwhelm the clean, clear broth.

Once you look past the queues, there’s much to take away from these hawkers aside from a da bao bag. Strip away the hawker title, and you’d see the resilience Singaporeans demonstrate in dealing with competition—being overshadowed by our peers, feeling the need to improve to succeed—is pretty much the same. We see it in our daily lives.

Mrs Lin believes in her food, and she believes that is why customers come back for more. “[Our] customers come to us because they want what only we can provide,” she says, before leaving for home. She intends to spend time with her grandchild before an early bedtime.

Once the clock strikes 3 AM, a new day of work for her begins again. She looks forward to it.