All images: Christy Chua & Ivan Kwee

It’s half-past seven, and the night feels like any other at East Coast Park. Joggers scuttle in body-hugging lycra activewear logging their step counts. Cyclists blast choppy Mandopop hits on rental bikes that creak with every pedal.

Skaters with unfastened helmets bobbling on their heads struggle awkwardly to keep their balance, and families chat in dispersed picnic clusters by the shore.

Somewhere nearby, is the epitome of grandeur for countless Taoist devotees; the highlight of the year—the Nine Emperor Gods festival send-off. It is hard to see where the ceremony is taking place, but a mysterious yellow fabric with an incandescent white glow by the coast may hold some clues.

Groups of devotees in white watch intently as two palanquins and a neon-lit boat descend through the crowd. Whiffs of incense smoke paint the coastline with a thin air of grey, as people kneel and hold up thick joss sticks to pay their respects.

Temple assistants in white begin charging in groups to release the dragon ship, which contains the divine urn of the nine gods, dashes of salt, oil, rice, incense paper, and joss sticks. As it drifts further from the coast, flames consume its paper shell, leaving hundred-odd devotees behind with a renewed peace of mind that bad luck is eradicated.

This dramatic sight to behold is what believers of Chinese folk religion anticipate every year, who worship gods and immortals that can be deities of places or natural phenomena, human behaviour, or founders of family lineages.

Called The Nine Emperor Gods Festival, this procession, rooted in Chinese cosmology, is a representation of longevity and salvation from misfortunes. Over the period of nine days, devotees go the extra mile in paying respects to the deities outside their day-to-day rituals and would spring clean the temple and abstain from the consumption of meat as a symbol of purity.

All this is observed as part of a greater need to gain protection and a semblance of security as they seek comfort in knowing that a higher order is watching over them. Unlike institutionalised religion, Chinese folk religion is syncretistic meaning that the worshipping of these deities is not limited to any ethnic or religious group.

Beliefs surrounding Chinese folk religion are cemented by folklore passed down over generations by word-of-mouth, without a scripture that is commonly adhered to by all.

While beliefs held may differ from person to person, devotees of Chinese folk religion share one thing in common: their connections to the myths which their deities originate from.

One version of the story behind the festival is that Goddess Dou Mu controls the pivot of the North Pole together with her spouse and nine sons, as the nine stars revolve under their surveillance. Devotees will perform the sendoff to honour and facilitate their journeys from and to Heaven.

“Think the story has got something to do with astrology and the nine stars… you can find it on Google,” a devotee explains with slight hesitation. “There is also another belief in Taoism that the Mother is taking care of the 28 planets, which comprises the star gods, and they have to be very careful with her.”

However, the devotee proved no more certain than Google’s unending list of search results. Numerous interpretations float across cyberspace, and no two temples offer the same story.

But more so, it did not matter which tale resonated with the majority—his reverence to Dou Mu Niang was enough to ring in the festivities. In a sea of stubbornly defiant devotees, it was all too clear that even safe-distancing restrictions could not deter them from fulfilling their responsibilities.

Most devotees attribute this togetherness to kampungs in the past, where temples were found near water bodies and that was the only way to welcome and send off deities.

“Maybe ‘cos you don’t come from a kampung, so you don’t know,” says another devotee. “Back then, this festival always took place near water and many children playing at the beach would experience it, since most temples would host it. It’s been like that for years already.”

But even if a singular origin story fails to prevail, devotees take heart in believing what works best for themselves. The values gleaned from rituals are often described by them as knowledge that even books fail to convey.

Conforming to age-old rituals has thus become part of their everyday lives, in hopes of passing on their versions of the stories.

Seeking answers that heal

As dusk descends upon Chia Leng Kong Heng Kang Tian temple, a black flag is hoisted by the door. A line of devotees forms in a tent outside the temple, waiting to divulge their problems to a prophetic deity that will take form in the body of Master Tan, the spirit medium of the temple.

The 53-year-old gives consultations to people who are in search of answers to both pressing and trivial issues—from the health of a cancer-stricken family member to lottery numbers. Aided by interpreters, dribs and drabs of statements from ancient Chinese folklore are dispensed like medicine. Vague at best, they serve to calm those fraught with anxiety.

The process of consulting a figure of authority to improve one’s mental well-being parallels that of Western psychotherapy, except for the eerie trance sequence and the monophonic chanting. This unorthodox mode of communication between the deity, interpreter, and the devotee has become a dependable fixture in their lives.

Joss sticks lit, wisps of smoke circle the room, and Master Tan’s ‘throne’ is in position by 7.30 p.m. Clad in neon green polo tees, his assistants wield rattan whips and wooden blocks that are used in the ritual. A choir of voices begin to chant from memory before Master Tan’s limbs start to shake uncontrollably, as if trying to ward off a horde of bees. His neck follows, head circles clockwise, and he finally gags and throws up.

The chanting ceases and Master Tan is no longer himself but a child deity. After he stuffs a neon pink pacifier in his mouth and slings an equally garish bag around his neck, he heads to the altar to pay his respects to temple deities. Now, he is ready to shine.

This ritual may be astonishing for first-timers to witness, but to Han Wei, it is plain as day. The 34-year-old has been Master Tan’s interpreter for more than five years. His scepticism was what led him to learn more about the workings of spirit mediumship alongside his day job at a cybersecurity firm.

“To be frank, I will constantly question whether this is real or not. Because if you think about it, I’m so-called educated and I believe in science, so this voluntary service is something that science can’t really explain,” he says.

“If you want to believe in something, you’d be willing to take the first step to understand your belief. If you’re in it, you’ll know.”

Science or not, Han Wei eased himself into his supporting role between deities and devotees while strengthening his Hokkien and ancient Mandarin vocabulary on the job. Even for someone with initial reservations, he shared that he was eventually convinced after being in the practice for several years.

“It’s like I suddenly connected with his wifi network,” he laughs. “Really. I’m being honest. I also think it’s ridiculous because, a couple of years down the road, I can miraculously understand what he’s saying.”

Demystifying mediumship

People are drawn to this form of consultation, as direct communication with the deity through mediumship is a form of instant gratification in desperate times. As prayers and divination lots pale in comparison to the direct discourse between a deity and a devotee, the personal connection fostered between them is what keeps devotees coming back time and time again.

Dr Lee Boon Ooi, a practising psychotherapist for over 20 years, says that when Western doctors or psychiatrists fail to heal a wound—be it physical or mental—people fall back on spirituality to explain phenomena.

However, this ‘magic’ that transpires from the process may be due to an ingrained belief that the deity’s advice is always for the better. It is like experiencing a placebo effect, Dr Lee adds.

Though some psychiatrists and psychologists suspect that spirit mediums may suffer from dissociative identity disorder, Prof Lee disagrees with the sentiment based on past studies.

The practice of mediumship is structured, conducted at a specific time and venue, is controllable; and most mediums do not suffer from clinically-assessed emotional distress or psychological impairment.

“Attention is a powerful thing because you know that somebody is very interested in you, knows your problem and is helping you. So this kind of attention given by the deity can be very therapeutic.”

Despite the oddity of the ritual—from Master Tan’s bodily reactions that defy logic, to a change in character after being possessed—it remains as an avenue for healing that devotees honour and respect. After seeing positive reinforcements to their lives, some devotees return to Master Tan on the regular.

“The mechanism is about hope,” says Dr Lee. “If I continue consulting this deity, I’ll get healed, or maybe one day I’ll get healed. It doesn’t really matter when it happens, but it will happen because I’m consulting a very powerful god.”

Living among the spirits

Mediumship advice is one of the multiple facets of spirituality in the lives of devotees. Lighting joss sticks, praying, and preparing offerings to these gods on altars serve as a display of loyalty towards these deities in a reciprocal relationship.

In exchange for peace and protection, devotees upkeep these prayer rituals and celebrate festivities such as the birthdays of deities annually, in a rinse and repeat fashion.

Two deities that are widely venerated in Singaporean households are the kitchen god (Zaoshen) and the earth god (Tudigong).

Zaoshen, who is known for protecting the home from evil spirits, originated from a tale of adultery where a man threw himself into the kitchen hearth, overwhelmed by the guilt of abandoning his wife.

On the other hand, Tudigong is a village guardian that protects the people and is commonly found in roadside shrines or in the back alleys of a neighbourhood.

These origin stories of deities hold a special significance for effigy makers like Ng Tze Yong, an apprentice craftsman at his family’s legacy business, Say Tian Hng. Having spent his childhood surrounded by hundreds of statues at the 126-year-old workshop, he has inherited not just the technicalities of painting facial features of deities, but a wealth of myths that they embody.

“I don’t see them as statues. I see them as stories,” he says.

The origin stories sometimes tell a tale of humans who possessed exceptional moral qualities and were deified after their deaths in honour of their contributions to the villagers.

“Unlike organised religion, folk religion is looser and perhaps a little untidy. But that is because it is driven by the common man’s sense of agency and yearning, and there’s something beautiful about that,” said Tze Yong.

While these inspiring acts of service would resonate with people for as long as devotees live to tell others about them, they also extend beyond humans.

This includes the monkey god, called Sunwukong in Mandarin, who has a dedicated temple in Tiong Bahru, as well as tree shrines, identified by a yellow ribbon wrapped about their trunks scattered across the island—the most prominent shrine being the Toa Payoh God Tree.

Interestingly, different communities approach the origin stories of the deities in their own ways. Varying titles have been given to the same deities in favour of different ethnic groups and gender preferences, but it is the beauty of believing in what the deities stand for that erases all differing views among devotees.

Zaoshen is portrayed as female in some stories due to their stereotypical domestic role, but newer stories have also allowed for them to be represented as male.

As for the nature god, he is commonly portrayed as a Chinese man named Tudigong but is simultaneously revered as Datukgong by the Malays, alluding to how someone of status is titled Datuk.

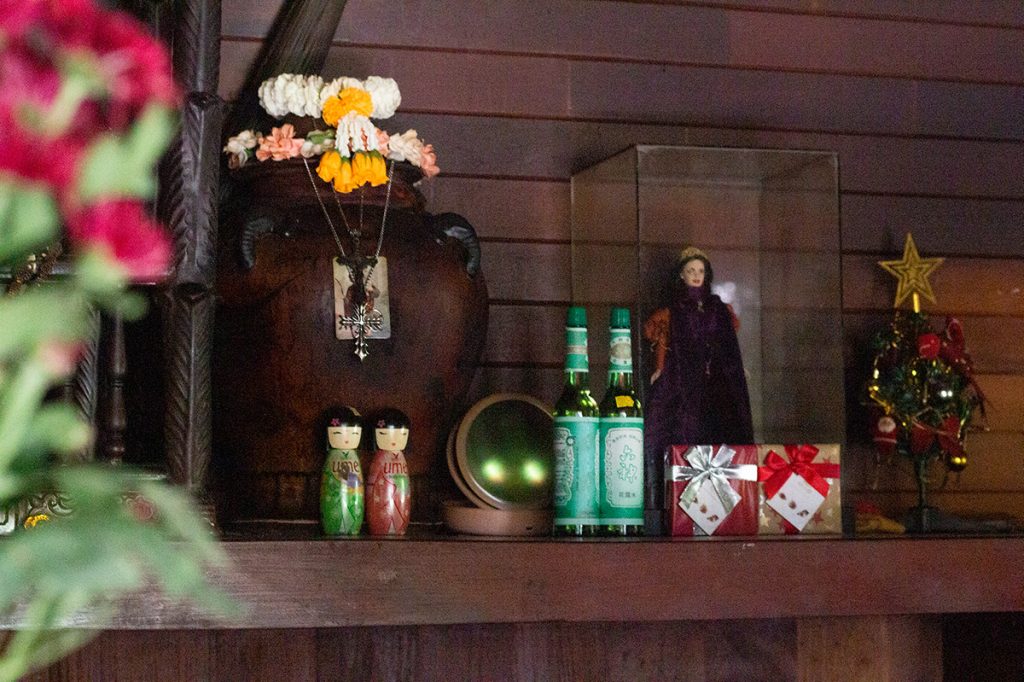

However, the deity in the German Girl Shrine on Pulau Ubin has been recognised as Datuk Nenek—the female version of Datukgong—since the legend was created. The ‘German Girl’ deity, represented as a Barbie doll encased within a glass container, never fails to pique the curiosity of Pulau Ubin natives, tourists, and Singaporeans alike.

Inside this iconic wooden hut, the doll sits beside a statue of Mother Mary, stalks of flowers and boxes of cosmetics as offerings. Its name is derived from the fictitious tale of a German girl who was found dead on this very plot of land after her parents were captured by the British military. The shrine, once heavily worshipped by workers at the neighbouring Ketam Quarry for protection, was built to commemorate her death.

“The German Girl is a new deity, only like a hundred years old. Maybe one day she will become as popular as Guanyin (Goddess of Mercy), who knows? The more people pray[ing] to her creates facts on the ground,” said Tze Yong.

While the credibility of the story remains a looming question today, it is intriguing that accounts by Ubin residents once made the headlines of Chinese and Malay newspapers between the 1980s and 90s. Each of these stories was spun very differently—the article published in the Malay paper Berita Minggu even claimed that the Barbie doll was a caricature of the princess of Java.

Nevertheless, these stories have served their purposes in their own times, and today, one can only look back upon documentation with wonder and make sense of them however they wish.

Making sense of deities

The German Girl Shrine, among others, remains a mystery for devotees to make sense of. As myths evolve over time, the influence of Chinese folk religion has seen its ebbs and flows, to the extent of transcending cultural barriers.

Tze Yong shares about a peculiar shrine he found in the alley beside 61 Duxton Street near Wa Don Don, a Japanese restaurant, with a doll-like figurine sticking out like a sore thumb beside the two Taoist underworld deities (Heibai Wuchang).

Upon consulting a Taoism group on Facebook, he discovered that the deity was baby Jesus, who is widely venerated by Catholics around the world. While he has no clue how the effigy found its way to the altar, he expressed fascination toward the inclusivity of Chinese folk religion.

“We may not know the origins of this baby Jesus figurine, but the fact that it hasn’t been removed and, in fact, is now worshipped alongside the Taoist deities, shows the open-mindedness of Chinese folk religion,” he said.

Seeing vibrant mandarin oranges and tall joss sticks on the altar is a comforting sight. These telltale signs made one thing evident—there are individuals who diligently upkeep these sacred spaces and will honour their beliefs for as long as they are able to.

Most of these age-old rituals and relationships with the deities have been passed down and sustained by the greying population. However, 20-year-old Krisada Virabhak has been following in his grandmother’s footsteps, from advice on respecting deities and learning to prepare offerings for them.

Krisada’s grandmother would remind him not to make rude comments if he sees people making offerings at trees or by the roadside.

“Later on, I realised it’s actually basic respect. You have to respect people’s beliefs, even if you don’t believe them, you should just let them be as long as you don’t get in their way,” he said.

Compelled to share his learnings from the spiritual world after participating in rituals such as the Nine Emperor Gods festival, Krisada archives these tidbits of information through the format of journal entries on his Instagram account, All Things Peranakan.

While meaningful discourse takes place on the platform, he still feels strongly about the fact that a lot of Peranakans go about their rituals without questioning.

He ascribes this to the fear of offending deities if they are not taken care of properly, as his grandmother refers to them as guests being hosted at a house. As such, devotees, fuelled by the pressure to keep up with these rituals, go on each day without examining the significance of these practices in their lives.

“They (deities) take care of you without asking for a lot of offerings; you can just offer whatever you can,” he said. “Even if it doesn’t make sense, I think they’re legacies that are passed down. If it’s not too hard or troublesome to carry out, then just do it, why not?”

Staying true to these beliefs is akin to keeping a candle flame lit amidst the interference of winds. It takes being part of a community to better appreciate the underpinnings of the invisible, guided by fiction that is backed by fact.

As a sea of devotees break into applause when a life-sized boat bursts into flames, the happiness that ripples back to the shore is priceless. It is something that devotees will never trade for anything more.

These ingrained beliefs, rooted in mythology, will continue to guide them in their lives, as long as they continue to find meaning in what they cherish and seek the answers they want to hear.

The questions can be saved for another time.