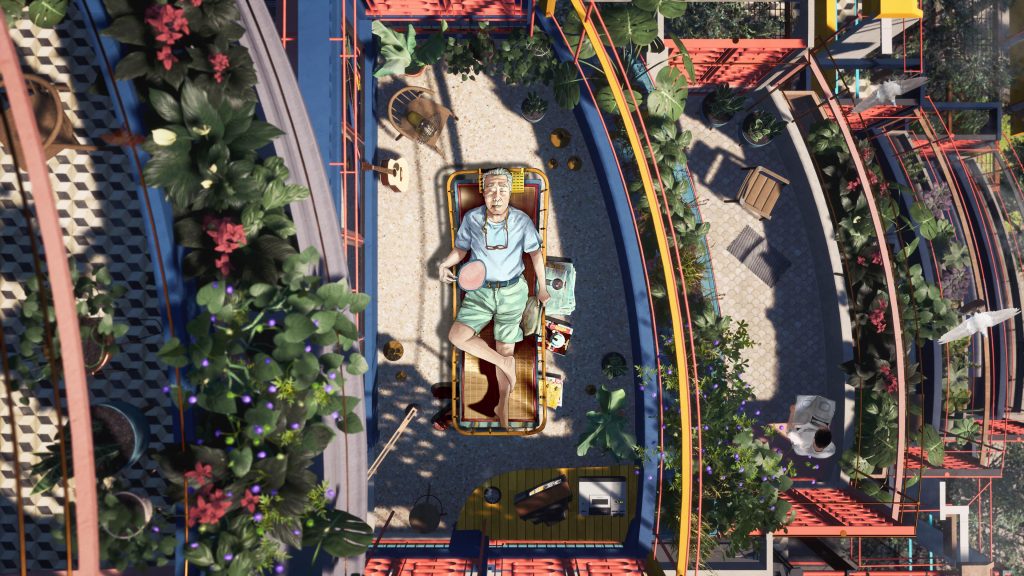

Top image: Jerome Ng

The demolition of Pearl Bank Apartments was the straw that broke the camel’s back for modern heritage advocates in Singapore. The private residential building, finished in 1976 and demolished in 2020, was a fixture of post-independence Singapore.

The modernist period of urban renewal—from the 70s’ to the 90s’— characterised the nation on its own terms by its own people. Pearl Bank, designed by Tan Cheng Siong, set a regional precedent for high-rise, high-density urban life in the tropics.

Among other ingenious design quirks, the condo’s horseshoe opening faced westwards to ward off the blazing afternoon sun. When the building fell into disrepair due to years of haphazard maintenance, an en bloc sale ensued.

The architect of Pearl Bank described his creation (and other modernist buildings, like Golden Mile Complex & Tower, and People’s Park Complex) as part of a “rich patina of social memories, which gives the city a sense of character and uniqueness that cannot be replicated elsewhere.”

Historic buildings hold an intangible value that is tricky to explain, let alone fight for—one either feels the importance of preservation or not. There’s also some inertia towards heritage efforts in Singapore with many factors contributing to this sluggishness. For a start, we have a complicated relationship with our tempestuous older buildings, many of which are in dire need of a facelift and some TLC.

Has the invasion of futuristic and formidable structures like Reflections, The Interlace, Marina Bay Sands, and Star Vista, reduced our capacity to admire the hallmarks from the past?

A thought experiment: imagine Singapore in thirty years.

I’m a catastrophizer by nature so, in my mind’s eye, our unique topography has disappeared—there are no more strata malls and peculiar hexagonal towers. Instead, the island is littered with imposing, cold reproductions of the glass edifices that tourists love to photograph. It’s impressive but, as a CGI model of new development, unfit for human habitation.

I suppose this stresses my anxiety about ceaseless demolition and high turnover urban renewal.

The question then stands: what do we lose when we pulverise the past?

Singapore, Dementia Nation

I’ve struggled to articulate our societal detachment from the physical environment. That is until I stumbled across an award-winning design project by a budding local architect.

Metabolist regeneration of a dementia nation (try saying that three times over) by Jerome Ng is a digital rendering of the Golden Mile Complex after radical, theoretical conservation. It’s a compelling prototype for heritage projects, complete with heartfelt testimonials about the spirit of Golden Mile Complex from its tenants.

At the heart of the rendering is Jerome’s assertion that Singapore is a dementia nation.

“When I heard about the demolition of the Golden Mile Complex I was very upset. I asked my friends back home: how can this happen? They weren’t disturbed at all, they said it’s normal. This is Singapore, change is the only constant.”

Ng mentioned that many of the buildings that are under threat of demolition via en bloc sales were pioneered by Singaporean architects. Losing these to impersonal, contextless developments would be a real shame.

Plus, our Singaporean structures are well-loved by the older generation. For our seniors, demolitions can be a disorienting and profound emotional loss.

“When I talked to some senior tenants who were moved out of en bloc buildings, I learned they link their sense of self to where they live. When they’re pushed out, it’s traumatising—and then they’re forced to watch the building crumble.”

As we talked candidly about our sentimental attachments to buildings that were torn down in Singapore, we realised that none of our favorites could have qualified for conservation. They were old, yes, but inconsequential.

For example, Mr.Ng’s saddest loss was a McDonald’s outlet. For me, it was the old shopping center in Holland Village with a windmill on the roof. The argument to conserve these spaces would be: I grew up going there, so it means something to me.

But in a land-scarce nation like Singapore, sentiment is a weak currency.

Nuts and Bolts: Why is Conservation So Hard?

I’m but a lowly journalist with little knowledge of architectural trends, terms, and debates. So, after speaking with Jerome, I made contact with some experts to learn the proper lay of the land in the conservation space. I reached out to the newly incorporated local chapter of Docomomo, an international non-profit which stands for “the documentation and conservation of modern movement.”

Docomomo’s focus on the modernist movement reveals a blind spot in our conservation dialogue: at present, heritage efforts are generally limited to the colonial past.

There are currently 6,500 shophouses gazetted for conservation by the URA (Urban Redevelopment Authority). The number of post-war buildings under the same protections is likely less than 10.

The local chapter was formed at the last minute after a failed attempt to save Pearl Bank Apartments. Founding members, Karen Tan and Dr. Chang Jiat Hwee realised that Singapore needed a more coordinated effort to advocate for conservation.

Dr. Chang is the Deputy Head of the Department of Architecture at NUS. While working with the residents at Pearl Bank, he noticed a curious double standard when comparing terms of consensus.

“For an en bloc sale to go through, only 80% of the residents need to agree. Whereas for voluntary conservation with an element of intensification [where additional developments are added to the existing structure, for example, the new tower at Pearl Bank]—the consensus must be unanimous. The bar for conservation can be higher than demolition.”

Though some residents at Pearl Bank were keen to pursue voluntary conservation, it was ultimately unviable without unanimous support from all the owners. However, Ms. Tan noted there has been a renewed interest in conservation from the authorities.

“In the last few years, we’ve seen an uptick in interest to conserve more post-independence buildings. But at the moment, our conservation guidelines aren’t flexible enough to accommodate some of the more nuanced cases, like Golden Mile Complex or People’s Park Complex.”

What exactly are we trying to conserve?

Though it’s shortsighted to demolish our physical history and heritage en-masse, it’s certainly not a malevolent act by the pragmatists in the URA.

Frankly, it’s easier to tear down and start over—the conservation of modernist buildings is a hill we haven’t climbed. Conserving a mixed-use strata mall is a different beast to restoring the facade of a few thousand shophouses.

Dr.Chang notes that for modern architecture, the inside is the ‘heritage’ part in need of conservation.

“Typically, it’s not what’s visible from the street that needs to be conserved in a modern building. The integrity of the building comes from the interior as well as the layout.”

The mixed-use (where commercial and residential tenants reside) properties are a logistical challenge, which Ms. Tan knows firsthand—her business The Projector is based out of Golden Mile Tower.

“Golden Mile Complex was one of the first mixed-use type developments. The intended use of the building became part of the conservation process, because if you allow the usage to change—what’s acceptable? Does it violate the integrity of the building? We all [authorities, developers, the public] need to talk about how we can adapt these buildings.”

Between Change and Stasis

Adaptive reuse is a term I noticed throughout our discourse on conservation and heritage, Ms.Tan explained it in layman terms as a negotiation between change and stasis.

“Adaptive reuse is a different approach to conservation. It’s not a purist process where everything is maintained or restored to its former condition. Neither is the building gutted. It’s a spectrum—where one weighs how much to keep, and how to adapt an older building to the current way of life. It can be done in phases, so a building can evolve with the public needs.”

Concurring with Ms. Tan, Dr. Chang further noted that adaptive reuse is not simply the process of restoring a building and turning it into a hotel. What makes this process a challenge for developers is finding the midpoint between the social, fiscal, and historic demands of conservation.

But that doesn’t mean it’s not worth pursuing.

“[Adaptive reuse] is a way for the government to make the past relevant for the present and the future. At the same time, it can be financially viable and even lucrative.”

Although adaptive reuse is somewhat unorthodox to developers in Singapore, there are success stories to admire as models of what can be done with other modernist buildings should they be gazetted as national monuments or heritage buildings. Dr. Chang believes that Jurong Town Hall is one such case.

“It’s a good example of a building which was sensitively conserved, but repurposed with a new use—JTC used it for some time, and now it’s home to the Trade Association Hub”

What can we save with adaptive reuse?

I’ve hammered on about what we’ll lose if we continue to redevelop at the speed we’re going, but Ms. Tan shared a hopeful projection of what we’ll save should developers focus some energy on heritage and conservation:

“Adaptive reuse is a way of building depth to a nation; physically, intellectually, socially. As a young country, we’re still in the process of generating depth. It’s a very human instinct to tie your social memories to physical spaces, and the fascinating thing about adaptive reuse is that the site of a new development is already full of history. The stories, emotions, and communities of an older building add an intangible value and build a richer urban fabric. More so than the current Tabula Rasa approach.”

The ‘tabula rasa’ approach is the incessant demolition I mentioned earlier. While this may have been prudent in the 60s’ and 70s’ when there were genuine urban dilemmas like squatters and slums, we’ve matured to a point in the national project where it’s time to stop and smell the roses.

In Dr. Chang’s view, the past and the future don’t need to be at odds.

“Many people think conservationists are against change. But we’re advocating for change in a different manner. We want the authorities to look for potential in buildings [for retrofitting and renovation] rather than demolition.”

What’s Next For Conserving Modern Singapore?

A major component of Docomomo’s organising strategy is to foster public discourse on conservation. They’ve achieved this in multiple formats—from organising a conference to participating in public talks and recruiting new members on social media.

It seems their efforts are making a difference. URA has proposed the gazetting of the Golden Mile Complex for conservation status—citing its innovative architecture and its unique chapter in the national story as the impetus to preserve. In fact, in the heritage & conservation proposal, URA used ‘adaptive reuse’ to describe how an en-bloc sale of Golden Mile Complex can take place without demolition.

The deadline for public feedback has passed but there’s yet to be an official confirmation of its rescue. While Golden Mile Complex is in limbo, Docomomo has turned their attention to People’s Park Complex and Pandan Valley—two other early examples of mixed-use, modernist developments in Singapore.

After speaking with Ms. Tan and Dr. Chang, I felt invigorated by their well-researched commitment to conservation. I raised Jerome Ng’s concept of the dementia nation to them, and Dr. Chang (who had viewed Mr. Ng’s project already) was particularly taken by his characterisation of our urbanisation.

“You know, I would take it one step further. I’d call it early-onset dementia. While initially we saw these modernist buildings as displacing our colonial past in the 70s’ and 80s’, they have, through the passage of time, now become our vernacular architecture. For many of us, the modernist urban environment is the only one that we’re familiar with. Now we’re trying to save the buildings which displaced our earlier past.”

He laughed and rubbed his temples wearily.

“Where does it end?”