All images by Xue Qi Ow Yeong for RICE Media unless stated otherwise

In December 1988, a month-long wait for driving lesson slots prompted one Straits Times reader to pen a forum letter. In it, the learner driver chastised Singapore Safety Driving Centre (SSDC) for allowing potential students to enrol “unchecked” without expanding its fleet of cars and instructors.

It’s nearly four decades later. A month’s waiting time doesn’t actually seem that bad right now.

In Singapore, securing a driving lesson slot might just be harder than actually learning how to drive—and that’s coming from someone who took three tries to pass her practical test.

Other learners and drivers I consulted all concurred that the entire learning process from start to finish was a bumpy ride, to say the least.

I’d also like to enter into evidence online thread upon online thread bemoaning the lesson booking process. Most of us probably know someone who’s thrown in the towel after life got in the way of driving lessons (I know of at least two). Ironic, because driving is still an important life skill wherever you are in the world.

But the crazy waiting times aren’t the story here. Our tiny island is home to 5.6 million people, 996,000 motor vehicles, and just three driving schools. Getting a driver’s licence is bound to take a while.

Instead, this is a tale of inertia—the inclination to maintain the status quo rather than innovate—and whether all our turmoils with the system are worthwhile in the end.

But before we get into all that, we must first understand the status quo.

The Path of Least Resistance

The system to get a driving licence in Singapore is pretty similar to ones overseas. You pick from one of three schools: SSDC in Woodlands, ComfortDelGro Driving Centre (CDC) in Ubi and Bukit Batok Driving Centre (BBDC) in, of course, Bukit Batok.

Once you clear your theory classes and tests, you get a provisional driving licence, and can start booking practical classes. After 20 to 25 lessons, you should be ready to book your practical test—the final gate to driving on the roads.

You can also opt for a private instructor for your practical lessons, though it’s getting harder to find one nowadays. The police stopped issuing private driving instructor licences in 1987, with the rationale that it was preferable to have dedicated driving schools with structured training programmes and better facilities.

I’ve been told by experienced drivers that the quickest way to get a licence is to do it fresh out of junior college or polytechnic—essentially your last big chunk of free time before university classes and work responsibilities enter the mix.

The idea is to book an entire block of classes, clear them ASAP, and move on to your practical test. Back in my post-junior college days, a few friends did exactly this. They attended several lessons per week (some even had multiple lessons per day) and obtained their licence within two or three months.

Unfortunately, I didn’t do the same. And I paid for it dearly.

My driving school journey at BBDC lasted the better part of two years, from 2019 to 2021. Booking classes and juggling work was a struggle. If I were lucky, I’d get one class a week. If there were no classes, I’d go a month or two without classes and forget everything I’d learnt.

In the end, I exceeded far beyond the recommended 20 lessons, and my wallet definitely felt it—each practical class is around $70 to $80. Including my three practical test attempts, the total damage was nearly $4,000.

A Bumpy Road

Other learner drivers from different schools echo the same difficulties.

The first issue with the block booking “hack” is that you need to have enough funds upfront, says Lianne, 30, a fellow BBDC learner who wanted to be identified by her first name.

At BBDC and other centres, you have to top up your student account with money before you can book classes. Booking a whole block of 18 classes (the maximum each BBDC student can book at a time) means you need to have over $1,400 in your account. Those who don’t have the funds to book in blocks have no choice but to take it one class at a time.

“They will have to spend more time just trying to get classes. And by the time they got to the next class, how much of previous learning can be retained? It’s a very expensive commitment.”

The other issue is that 18 classes just isn’t enough, says Lianne. Based on her friends’ recounts, they took an average of 22 lessons to finish the automatic car driving syllabus. For their remaining classes, students will have to constantly refresh the website for last-minute cancellations.

“Eventually I had to go to the receptionist twice to beg for new classes because who has time to stay glued at the computer and refresh the screen for 24 hours?”

And then there’s the waiting time before you can even book your first lesson.

Daniel Ko, 19, who obtained his licence at CDC, says that new slots open up every month, but those are for two months out. It’s “very hard” to secure slots because of bots, he alleges.

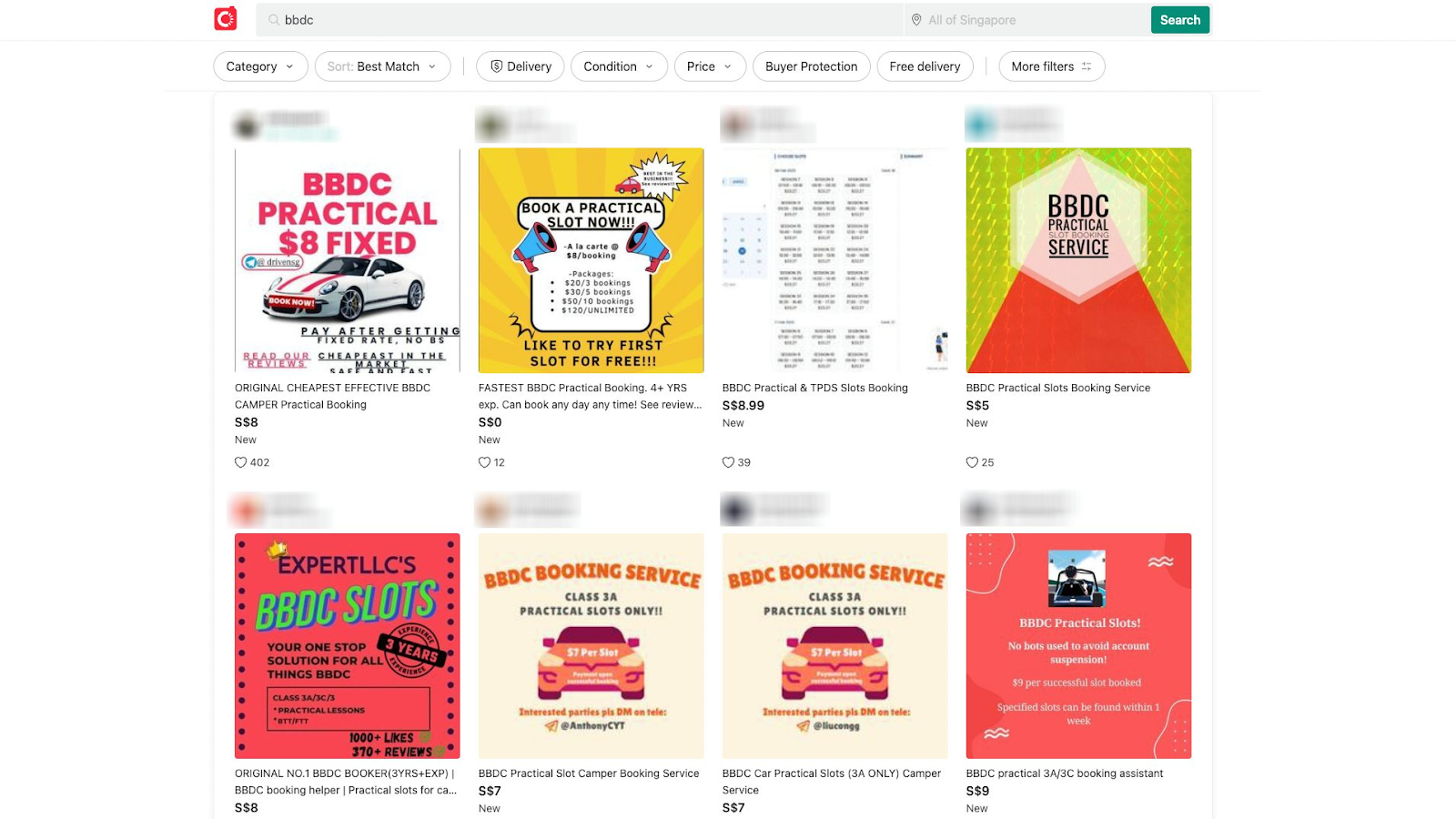

Indeed, a search for all three driving schools on Carousell reveals aspiring entrepreneurs offering to book lessons for as little as $5.

Some do employ the services of bots. Others are simply selling their time. One Carouseller promises a full-time team of five who’ll log in to your account to book slots for you. There’s no automation involved to avoid suspension by the driving school, they claim.

Over at BBDC, a student who wanted to be anonymous says she was told recently that she’d need to wait six months for the next practical lesson.

“I’m really freaking frustrated. And I was thinking: What about all those other people who don’t really have six months or don’t have the time to do this?” the 31-year-old shares.

She also takes issue with the evaluation tests that schools require students to pass before actually sitting for their theory tests. Of course, these take time to do and aren’t free. Even though the waiting time for these evaluation slots can be just a couple of days, it’s yet another hurdle to jump through in an already lengthy process.

“The people at BBDC even showed me the Traffic Police website—apparently, they have the highest passing rate for the final theory test. And yeah, it’s because of the evaluation. If you don’t pass your evaluation, you can’t take the real test, which is very Singaporean.”

These evaluation tests are essentially a way of making sure only students with a high likelihood of passing get to take the official tests. But is this for the students’ own benefit or the schools’?

Trevyen Darukhanawalla, who got his driving and motorcyclist licence at SSDC, feels that it’s the latter.

“This literally benefits nobody other than the schools since you are spending money and time to go for these useless exercises which are not an official requirement [by the Traffic Police],” says the 21-year-old.

Speed Limit Ahead

Students are mainly resigned to the way things work.

Alarice Teo, 19, a CDC student says: “Learners either learnt to accept that things will remain the same for the duration of their learning journey. The voices of the learners are not that strong.”

She adds that at the end of the day, after graduating from the school, these gripes all become a thing of the past.

Still, there are some who think the system needs changing. Trevyen has some strong words.

“I reiterate that I have nothing against [Traffic Police] or any of these driving schools, but the fact of the matter is they are simply not interested in helping you to obtain your licence and want to make the process as challenging and arduous as possible—somebody needs to hold them accountable.”

When I took these complaints to the three driving schools, I didn’t get the sense that much change is on the horizon. If anything, they offered a glimpse as to why things are the way they are. At least BBDC and CDC did—SSDC didn’t respond to our requests for comment.

Both driving schools said they have progressively been hiring more instructors to cope with demand.

Even though CDC aims for a seamless learning experience, external factors can sometimes impact scheduling, a spokesperson explains. For instance, the pandemic caused a backlog, which the school addressed by extending operating hours.

“However, driving schools operate within a larger ecosystem with other stakeholders, and factors like instructor availability or external licensing processes can influence lesson and test scheduling. This multi-faceted nature means some things are beyond our direct control.”

It’s worth considering that all three driving schools are pretty much operating at maximum capacity. They aren’t wilfully withholding lessons from students, at least.

Lessons are held on weekdays and weekends, with slots stretching from the crack of dawn to nighttime. There are limits to how many cars can be on the circuit at once—circuits also have to be shared with students of private driving instructors.

BBDC states that, on average, a student with no driving experience takes about eight months from the date of enrolment to obtain their licence. Practical slots are released at “full capacity” based on manpower. Necessary actions have been taken against bot users, but they’re “unable to stop Carousellers”.

Evaluation slots are also mandatory in the training structure, both schools said, but didn’t elaborate on why.

Do both schools feel like the current driving school model works well at meeting students’ needs? BBDC says it does. Their spokesperson affirmed: “Yes. BBDC have been operating for more than 30 years and provides comprehensive and systematic training towards road safety education.”

That’s fair. But it didn’t really answer my question.

CDC didn’t explicitly say yes, but highlighted the varied needs of students. Beyond just practical skills, safety is key: “Through a comprehensive curriculum, jointly developed with the Traffic Police and industry experts, we aim to foster a strong safety culture, empowering future drivers with the knowledge and mindset to navigate roads responsibly.”

Both schools also say they’ve been working on improving their services. CDC, for example, added four new driving simulators when students complained about simulator waiting times. It’s also introduced new tech such as the Driver Development Tool in its vehicles, which used technology to provide immediate feedback to learners.

BBDC maintains that it has been continuously recruiting suitable candidates, but the employment of instructors is one of its challenges.

Shifting Gears

There’s a disconnect here—generations of students bemoaning the system they have no choice but to go through if they want a licence, and schools that think the system is generally working well. But if so many people have been complaining about the system for so long, surely there’s a better way to do things?

Of course, there’s a reason why things are the way they are. Currently, all three driving centres are privately run. In 1996, the then commander of the Traffic Police explained that privatisation was due to manpower shortages.

Doing so would allow the staff stationed at Kampong Ubi Test Centre, which used to be run by the Traffic Police, to be deployed elsewhere, he explained.

But maybe the issue is that there simply isn’t an incentive for driving schools to majorly change the way they do things. When it comes down to it, the driving centres probably have more students than they can cope with (hence the crazy waiting times).

The three centres operate so similarly that most of us simply end up picking the centre that’s closest to us. They don’t need to compete.

In fact, a check on ACRA shows that BBDC and SSDC have several directors in common. Japanese nationals Takanori Maruyama, Yuta Nino, and Hideaki Takaishi are directors of both SSDC and BBDC.

Both public companies also have a shareholder in common—Income Insurance is the biggest shareholder in both.

The close relationship isn’t surprising. Back in the ‘80s when BBDC was first set up, Honda was a stakeholder, along with SSDC. But it also indicates that they probably aren’t trying too hard to one-up each other.

It’s hard to see how change can happen. Could we do with a new driving centre? Or a revival in private driving instructors? Or perhaps a new circuit where private instructors can teach, freeing up school circuits for school learners?

Or, maybe, as Trevyen suggests, the solution could be to introduce a quota system where schools take in a fixed cohort of learners and give them a fixed period of time to clear their licence. In the meantime, those who want to enrol will be on a waiting list until a sufficient number of people graduate.

At the end of the day, we can’t say for sure if it’s a viable fix. The feasibility of these ideas needs to be studied. But even before that, we need the people in charge to acknowledge what students have been saying for years—that the system can and should be better.

Do We Actually Need a Driving Licence?

The bigger tragedy, though, might just be the fact that some of us are trucking through the driving school system to obtain our licences, only to tuck them away in our wallets, unused.

It’s been two years since I got my driving licence. And as much as it was a relief to finally close my BBDC account, I have to admit that I haven’t actually driven much. In fact, I might have forgotten how to parallel park altogether.

I don’t think I’m particularly unique. Though most of the people I know have licences, a small minority actually drive regularly.

I used to think driving was a rite of passage to adulthood. When I entered my late twenties without a licence, I felt a little inadequate. The last straw came when I headed to the US with six friends for a road trip. There were only two drivers in the group. The defacto drivers were happy to take the wheel for hours, but I told myself it was time to stop being a passenger princess.

When I got back to Singapore, I enrolled in BBDC. Did I really need a licence, given that I don’t own a car (and likely never will)? Probably not.

Singapore has one of the best public transport systems in the world. You can pretty much get anywhere relatively quickly and for not that much money. Unless you have kids or elderly parents, ride-hailing might prove to be more convenient—and economical— than driving your own car.

Not to forget that this country holds the dubious honour of being the most expensive country in the world to buy a car. Before you even sign the papers on your vehicle, you’ll have to shell out about $100,000 for a Certificate of Entitlement (COE). The price means car ownership is out of reach for many. That’s not even counting the road tax, parking fees, and vehicle maintenance.

It’s steep enough that those who can afford it are thinking twice—and steep enough for people to reconsider if a driving licence is worth all that trouble.

Owning a car isn’t even the status symbol it used to be, according to a 2022 Straits Times survey. And yet, remnants of that mindset remain.

Here’s a question to consider, then: What freedom awaits us if we just accept the fact that we don’t need to know how to drive?

In retrospect, the idea of driving as a rite of passage seems outdated—a relic of our parents’ time when public transportation was less developed. Back then, a car was essential for venturing off the beaten track. These days, most people who drive private cars do it because they can afford to.

Funnily enough, it seems like our driving aspirations are changing at a faster pace than our schools ever will.

For me, at least, a driving licence is not so much a passport to freedom but a symbol of what I went through: those lessons I fought so hard to book, the curbs I mounted, and all those tests I failed.

Am I happy to have a licence? Yes. Do I wish I’d saved all that time and money? Also yes.