In ‘Singaporeans Abroad’, we share the stories of locals who—thanks to living in a globalised world—have found success in different corners of the globe. Whether financially, romantically, or for the pure joy of adventure.

We’ve recently heard from Jing Rui, whose decades of battling severe eczema and topical steroid withdrawal led her to set up her own skincare clinic in the UK. Then, there was Chef Nora Haron, who’s flourishing in the buzzing food scene of sunny California with her take on Nusantara cuisine.

Now, we bring you Fabian Low, whose early struggle with an identity crisis while living in Singapore guided his search for a sense of self and led him to his tiny house in New Zealand.

All Images courtesy of Fabian Low unless otherwise stated.

My tiny house, which is 10 metres in length and three metres in width, has garnered far more attention than I could ever imagine.

Shipping containers inspired the house’s exterior. The facade bears a monochrome black and white exterior and stands out among the surrounding green pastures, like an accidental ink blot on a painting.

I engaged a builder in New Zealand to build the exterior. It cost me NZ$220,000 (S$185,140). The deck outside was an additional NZ$30,000 (S$25,250). It’s a two-storey space with a fully equipped kitchen, a cosy living area, and a bedroom on the second floor.

In the bedroom, a projector hangs overhead and projects onto the opposite wall—for entertainment. The living area might be small. But why have a big house and fill it up with things you eventually will lose interest in? Instead, I’ve always believed in having a small house and being content with what you have.

My beliefs are part of the larger (haha) Tiny House Movement. The movement prizes simplicity in your way of life, freedom, and sustainability.

These are values which I’ve believed in for much of my life—I’m 44 years old this year. I’ve done a whole bunch of different professions; community-building, musician, gardening, and a whole bunch of stuff. I don’t like to be defined by them. But I guess everything led me to what I want to do next, which is counselling.

That’s what I’m studying for right now. I’m doing part-time studies in counselling and part-time support work as a mental health practitioner in Auckland. It’s a short drive from my tiny house.

My focus is on narrative counselling. I realised the stories we tell ourselves shape who we are. And much of my life has been spent creating a narrative for myself, resisting dominant narratives others set for me. I believe narrative evidence goes deeper because you find evidence within their own stories.

I’ve been moving between different things while living in my tiny house. So when global media attention shined its light my way, the positive response it garnered was a pleasant surprise. To me, it was just a part of my lifestyle.

I cherish the home that I’ve created for myself. But my journey towards getting this tiny house has been far from smooth sailing.

Leaving Singapore

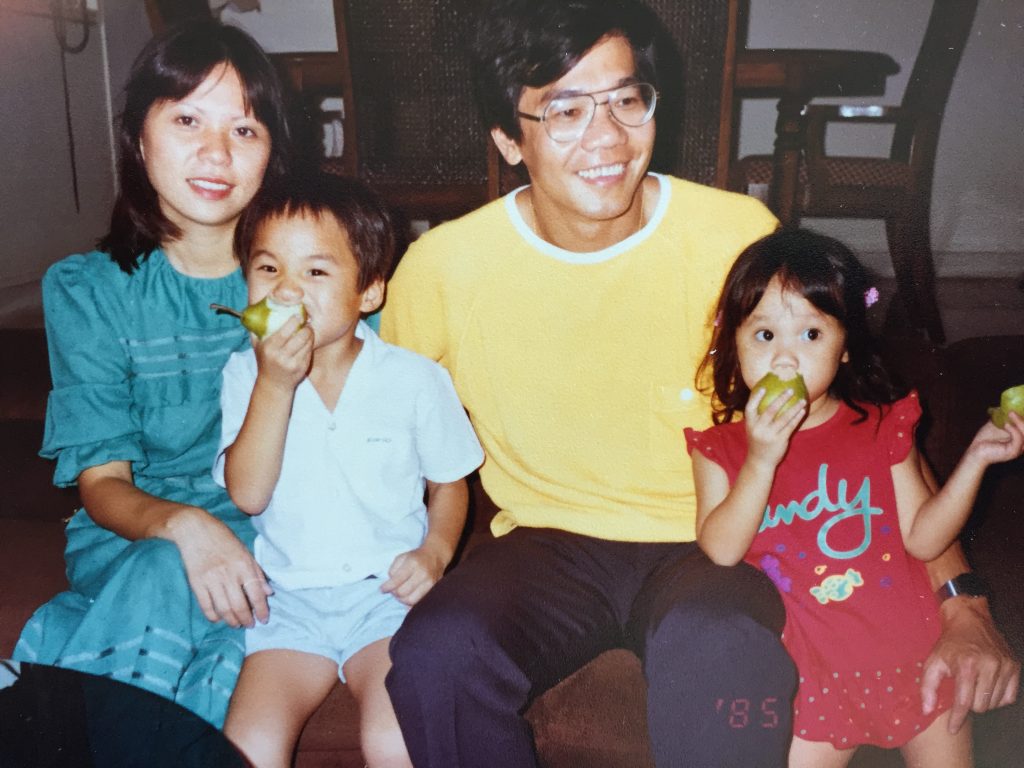

My parents relished the opportunity to uproot our family and move to New Zealand. According to them, it couldn’t have come any sooner. I was a terrible student in primary and secondary school in Anglo Chinese School.

My secondary school days in the ’90s were blissfully wasted away along the air-conditioned corridors of Takashimaya and Far East Plaza. Going home to face my parents’ questions rarely crossed my mind—I was a bit of a rebel from the start.

I did well to an extent, but I often confronted the feeling that my best wasn’t good enough in my parents’ eyes. I stopped trying—school just wasn’t for me, I decided.

In Singapore, I felt like a failure. Where countless other Singaporeans have survived, even thrived, I’ve failed. The academic pressure cooker was too much.

Closer to home, my sister’s academic achievements were a spectre which hung above my head and haunted me through my childhood. She was the picture-perfect image of a good student.

When the opportunity to move to New Zealand presented itself, it was a chance to start afresh and a lifeline for a struggling student like myself.

In 1994, my family and I left for New Zealand at the tender age of 14—in the middle of secondary three. If I had continued schooling back in the Little Red Dot, I suspect I would have choked quite easily at the national exams.

The academic pressure, which suffocated me, seemed to be easily shouldered by my peers. I felt like I didn’t fit into Singapore because of it.

Leaving for New Zealand felt like a fresh start initially. But I was wrong.

Finding a Place To Belong

I stood out in New Zealand much like I did in Singapore.

Christchurch was overt with racism. Decades ago, it was much less multicultural than a metropolitan area like Auckland. My Asian face inadvertently raised alarms. Locals assumed I was from a deep part of China. They were not used to seeing foreigners in the community.

I remember waiting for a bus after school on my way home. I was minding my own business, careful not to raise eyebrows. My mundane existence, however, caught the attention of a stranger. The stranger approached me and requested that I “go back where I came from”.

“What do you mean? I am on the way home. I’m waiting for the bus. It just hasn’t come yet,” I responded. Cheeky comments were an easy way to weasel my way out of a direct confrontation with the person—humour was a convenient tool to brush racist incidents off my back.

Barring a handful of serendipitous encounters with primary school friends who also moved to New Zealand, I felt lonely. My Singaporean accent stood out and raised puzzled looks among students who had yet to be exposed to any other accent outside of theirs.

Although New Zealand was supposed to be a fresh start for my younger self, I was still an outlier. I struggled internally and didn’t fit in or feel validated or accepted in whatever context I tried to apply myself to.

It’s ironic that I finally found a place to call home with my tiny house when I returned to New Zealand for the second time.

The Burning Man Experience

After graduating high school in Christchurch, I moved to Auckland and spent some of my working life there in the city. I’ve done other things besides narrative counselling. Beyond practical concerns, I wanted to come to terms with my low self-esteem to build myself up again.

Deciding that another environment would do me good, I flew to Vancouver in 2014. I had no plans, no idea of how long I was going to stay, and barely a job lined up for me. It was a journey of self-discovery.

Maori culture in New Zealand cultivated my interest in spiritual themes. I was particularly interested in their beliefs, worldviews, and how they relate to the world. The only thing I was sure of was learning more about the same themes around Native American culture in Canada through community festivals and ceremonies.

One of those festivals was the famous Burning Man event, which is held in Black Rock Desert, Nevada. I attended my first Burning Man in 2014. This was something I had been looking for, with its focus on community and self-expression.

Burning Man is a seven-day event that ends with the burning of a giant wooden effigy on the event’s penultimate night. The burning represents the irreverent expression of “sticking it to the Man”—an outward demonstration of defiance in the face of authority.

Colourful tents and banners were propped up in the middle of nowhere. In the distance, haphazardly parked roving camper vans seemed to mesh together in a maze of glistening steel and hot rubber. They surrounded the festival’s epicentre and expanded outwards into the horizon.

The camper vans were essentially tiny houses in and of themselves. Communal living, and its focus on self-reliance and sustainability, were important lessons I learnt.

Burning Man showcases the importance of immersing yourself in an environment that helps you grow. An environment can build you up, but it can tear you down just as quickly. I was so enamoured with the idea that I attended it three more times after that.

I was reminded of Singapore. The pressure to excel and conform turned my inner voice against me. I tore myself down when I should have been showing myself compassion.

Think in Circles, Not Blocks

The Sun Dance Ceremony was the last activity on my itinerary before leaving Vancouver. I would have loved to stay there to keep the vibe and energy going, but my visa was running out, and I couldn’t afford enough points for a permanent residency.

The Sun Dance ceremony, celebrated annually on the Canadian plains, is a sacred celebration practised by some Native Americans in the United States and the Indigenous people of Canada.

Sun Dance practices can be quite challenging to witness to the uninitiated. Participants take part in the ceremonial piercing of the skin, fast from food and water for extended periods of time, and partake in a gamut of trials of physical endurance.

When you understand that the ceremony is celebrated because participants intend to reaffirm their beliefs about the universe, the Sun Dance ceremony is a beautiful celebration of gratitude.

On the last day of the ceremony, I approached the Sun Dance Chief, White Standing Buffalo—a social worker and an amazing storyteller.

I offered him tobacco, a custom offering in his culture, and asked for wisdom. He accepted the tobacco and started chatting with me.

I told him where I came from and what I was doing there. Before I can go any further about what I was looking for, he interrupts.

“You think in blocks. The society you live in makes you think in blocks, lines, and squares. But if you really want to understand the Native American path and your spiritual essence, think in circles.”

I was speechless.

His advice could have easily been dismissed as new-age mumbo jumbo to an insincere listener. It took four weeks to pry any semblance of meaning from the wisdom he had given to me.

I realised that blocks get you from point A to point B in the fastest way possible—a mindset fixated on efficiency like in Singapore’s. When you think in circles, you rely on logic much less; your head is less important. You rely on your senses and heart.

The connection between these parts creates a spiritual awareness of life’s bigger picture; some things cannot be explained by logic sometimes.

And my upbringing meant I was still deeply shaped by the linear mindset. I had not fully escaped it, even miles away from home.

Thinking in circles helped me realise that everything is much larger than the categories we confine ourselves to. It’s perfectly fine to feel comfortable as yourself without putting a label on it.

All That Glitters Is Not Gold

I returned to New Zealand in 2017, more confident of who I was. Inspired by the tiny houses and communal living I saw at Burning Man, I wanted to recreate that for myself.

The land my tiny house now stands was first gotten through a local website which champions the tiny house movement. New Zealand’s tenancy laws, much like the country’s culture, are very lax. Informal tenancy agreements between landlords and tenants are the norm.

And, fortunately so. I reached an informal agreement with our current landlord, who was looking for an additional income source at the time. The plot of land I had gotten overlooks stretches of green pastures and open skies.

While the scenery is breathtaking, it is ultimately a plot of open land away from the city. I was left to my own devices to build a house that I envisioned for myself. And the tiny house came into being through no small effort.

Living so close to nature comes with a price. Being away from the comforts of modern infrastructure meant I needed to figure out how to breathe life into the house’s soulless exterior. I put my degree in architecture to good use.

Attempts to connect the house to basic utilities like electricity, water, and a waste disposal system questioned my resolve about having a tiny house in the first place. Before the house had a septic tank, I sat on a plastic pail in the middle of green pastures under the Milky Way for a month.

I didn’t calculate how much it cost me to connect my tiny house to basic utilities. But the process was a team effort. I offered friends beers and pizza in the evening after a hard day’s work of digging a trench deep enough to house the septic tank. I’m fortunate that New Zealand has a strong DIY culture.

The initial stages were challenging, but I was determined to carve a space where I could fully be myself, inspired by my lessons from Burning Man and the Sun Dance Ceremony.

A Place To Call Home

I wanted the interior of my house to be a personal shrine to my journey. They represent my past, the person I am now, and who I envision myself to be in the future.

I have shells from the South Islands of Singapore on my bathroom sink top, reminding me of the time I spent along the beaches with my father when I was younger.

Outside my house is a garden and farm that I tend to. I don’t need to take my car anywhere because the food comes from the garden. I grow red chillies in my garden and use them to cook laksa when I miss the taste of Singapore.

Llamas and goats saunter freely in the pastures. We have fresh eggs from the chickens we rear. And sometimes, when I’m craving chicken rice, we slaughter one of the chickens for a feast.

The space might be small, but it means much more to me than just a shelter over my head. As someone who struggled with my identity in my early years, the house is a physical manifestation of who I am.

I deeply cherish the feeling of finally fitting in, especially for someone who struggled with an identity crisis in my younger years. Home, to me, is where you can really be yourself. And you can carve a space out for yourself in Singapore or abroad.

Tiny House, Larger Than Life

That being said, I don’t have all the answers.

I was hesitant to share my tiny house with the world at first. I didn’t want the news to reach my mum because she disagrees with the lifestyle. I understand that she means well, but she’s very much informed by way of a typical tiger mum.

There are sacrifices I’ve made to build the lifestyle I’ve wanted. To have my independence, I needed to distance myself from the family.

The only reason I relented and agreed to share my lifestyle with the world was that I figured that not many Singaporeans would watch the video of a tiny house. But it was bad judgement on my part.

I understand that societal stress is very high in Singapore. BTO flats are expensive, space is scarce, and not many Singaporeans get the opportunity to move overseas.

However, I hope Singaporeans can find a space for themselves to paint their personalities on a canvas. For the average person living in an HDB flat, your room can be that space to play—personalise it in your own way. Even if you’re constrained within a box, you can also think outside the box within the box.

Think in circles, not blocks.