All images by Lee Xian Jie.

In ‘Singaporeans Abroad’, we share with you the stories of locals who—thanks to living in a globalised world—have found success in different corners of the globe, whether financially, romantically, or for the pure joy of adventure.

We’ve recently heard from Dwi, who went to LA for community college after failing her A levels and eventually found herself working in Goop. Then, there was Mariah a military wife turned fitness instructor who is now a ‘natty’ bodybuilder in Texas.

Now, we bring you Xian Jie, a documentary production assistant turned tour guide in Japan, in the midst of restoring a 120-year-old traditional Japanese house

When I was in Singapore, I was a documentary production assistant for Lianain Films from 2011 to 2016. The company produced films about pollution in China and reported on the state of democracy in Hong Kong.

I found myself in Japan in 2012 to pursue a political science degree because I was starting to report on political stories in China.

But honestly, I just wanted an excuse to spend four years in Japan.

Now, I run a farm in Ryujin-mura, a village in Japan, with about 10,000 square metres of land. Here I grow various crops—tea, yuzu, tomatoes, and lady’s fingers, depending on the season.

On top of that, I also run a cafe on Fridays and weekends at a 120-year-old kominka, a traditional Japanese house, located on the property.

I’m still in the midst of restoring the house, though; I’ve already spent close to S$25,000 from my savings and used money from when I was a tour guide in Japan for repair and refurbishment works.

It’s rickety and old, but I couldn’t be more proud of the progress I’ve made to the house since I started.

Curating Alternative Tours in Japan

After studying in Japan for four years, I wanted to find a way to live in Japan. I started a tour guide company called Craft Tabby with some friends. That was in the year 2017.

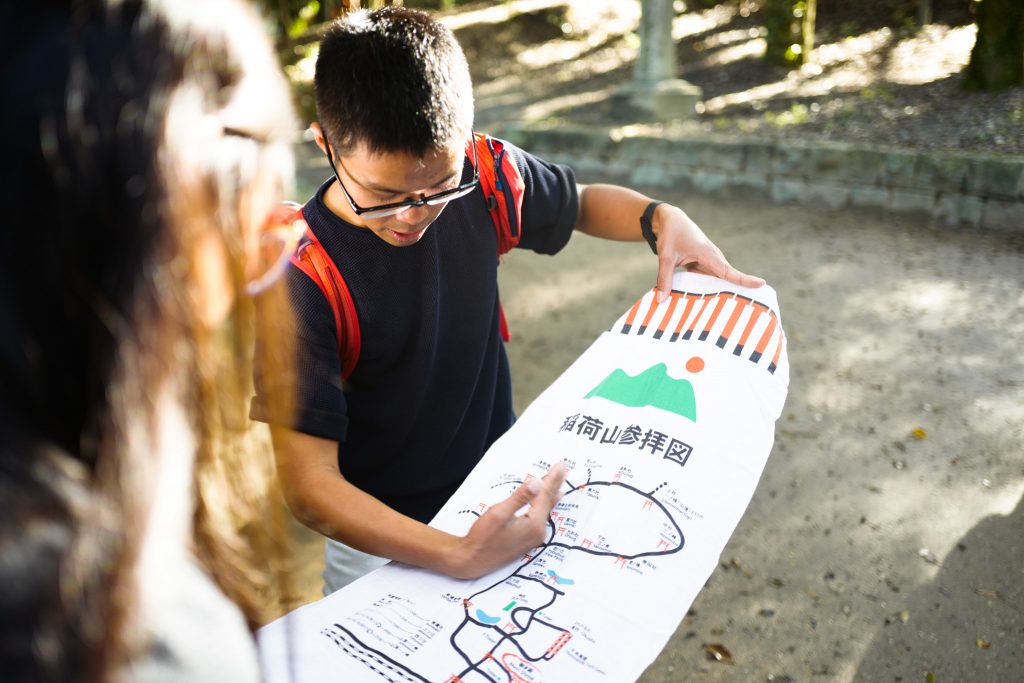

Craft Tabby specialises in walking and cycling tours that shows visitors another side of Kyoto. We did this tour in Kyoto called the “Alternative Fushimi Inari Walking Tour”, where we delved into the history and architecture of vermilion torii gates.

But instead of just taking photos of the gates, we visited the waterfalls around Kyoto, spoke about Shintoism (the religion these gates come from), and discussed the plants surrounding the grounds and the spiritual connection between the forests and the people there.

At one point, this was the highest rated tour on Airbnb and TripAdvisor.

Then, we also had “The Hidden Water Cycling Tour of Kyoto”, where we would ride through the city on electric bikes and learn about underground water sources for Kyoto’s wells and natural springs. They are often focal points for folklore and local history, so visitors to Kyoto get an overview of Kyoto’s sordid tales and spiritual stories.

When the pandemic hit, all physical tours had to stop. Airbnb, where we hosted our tours, asked me to do something called ‘Online Experiences’. Trying to condense a three to four-hour experience into just one hour was challenging. But I decided to try and start this virtual experience called “Flower Hunting In Kyoto With Mori The Doggo”.

It was quite an adorable experience because Mori was a wild dog who had lived in the forest for two years and had an appetite for the edible flowers in the garden. A GoPro would be strapped to Mori as she explores gardens identifying all sorts of wild, edible flowers.

Restoring a 120-year-old Teahouse

In Japan, at least for me, everything starts and ends with tea. I was at this tea festival five or six years ago, where I met a 70-year-old man named Shu. I remember him because he was the only person not selling tea and, instead, was giving away his tea for free.

I took a sip of his tea and asked him how it was made. “Come to Ryujin-mura (a village in Wakayama prefecture of Japan),” he says, “and I’ll show you how to make this tea.”

Needless to say, I fell in love with the sights and sounds of Ryujin-mura. Initially, I had pegged this village as somewhere I could retire in the distant future. But with the onset of the pandemic and with help from Shu, I was settling in Ryujin-mura a little faster than I thought.

Shu showed me a house he knew was available for rent that had been empty for some time. It is rare for a foreigner to rent a house in Japan. The locals worry about what you would do to their building.

When I say foreigner, I don’t mean someone from another country. ‘Foreigner’ could also mean someone from another city. To people in the village, anybody not from the village is a foreigner. So if you’re from Osaka (another city in Japan), chances are that they will not rent a house to you because you are a ‘foreigner’.

In this case, after help with negotiation from Shu, the landlady said yes pretty quickly, but there was a catch. The building was quite dilapidated and needed lots of repairs. I thought, well, if I’m going to repair something, it’s going to be this 100-year-old house; I wasn’t going to fix up a modern house.

The draw of a kominka is that the structure is very open; it’s like living in nature. You have pine trees as floorboards and big sakura trees as pillars. These houses were also built no later than the Second World War, so I wanted to preserve the architecture as much as possible.

I documented much of the process on my YouTube channel—from the extensive rules of buying property to the nitty gritty of clearing rain gutters and floorboards and how the physical appearance of your property bleeds into social conventions. In Japan, the cleaner and more well-kept your house, the more trustworthy you are perceived to be.

Living in Rural Japan

The main draw for me to live in Japan is the sense of space. Ryujin-mura is about one-third the size of Singapore and only has 2,900 residents.

Most people think that Japan is crowded, and that’s because almost 80 per cent of the population lives in cities; the other 20 per cent can be found in rural area.

During Covid-19, we didn’t have to isolate ourselves because each house had such a huge area of land surrounding it. None of us needed to wear masks. After all, our homes are, on average, about 50 metres apart, and we can just stand outside them talking.

One thing I discovered about living in rural Japan is that you need to get along with the neighbours. If I had come and started a restaurant immediately, there wouldn’t be any local support. By spending a year renovating the building and fixing it, I got to know the carpenters pretty well, and from there, they introduced me to more tradespeople.

I know the plasterer, plumber and electrician from the carpenters. They will start talking about you and putting in a good word for you, saying, “Oh, there is this Singaporean guy, and he’s making tea.” That way, everyone starts to get to know you.

But if you ever decide to come to a rural village to live, there are things you must pay attention to.

Property boundaries, for instance, are very strictly adhered to here. It’s the same for community participation. On New Year’s Day, there’s this little gathering at the shrine everyone must go to. If you don’t, it’s a huge social faux pas.

We also have a grass-cutting event every year, where we have to cut grass together for a morning. In a sense, they are compelling you (but in a nice way!) to participate since you are part of the community.

If you see this as a restriction, it wouldn’t be very enjoyable. I see it as something fun, so I don’t feel bogged down by this obligation. In a village like this, there is a strong sense of community that is often absent in bigger cities such as Singapore.

Here, we don’t have a neighbourhood association; we appoint a hamlet chief instead. The chief is chosen by us and not by any government body. He is in charge of everything in the village, from the infrastructure to finding missing dogs.

In the village, everything is done from the ground up—literally, sometimes. When the roads are in poor condition, if the hamlet chief can, he will repair the road himself. It’s not an exaggeration. If the authorities are delayed, he will pour sand and even cement on the road to start the process.

In the countryside, there’s a sense of obligation to constantly attend and participate in village activities. It can be suffocating for a person born in a village because everyone knows everyone else’s business.

But the great thing is that the community takes care of each other.

From Production Assistant to Managing A Tea House

Life has changed so much from when I was a production assistant. There is still a certain amount of stress that comes with this life, but it’s a different kind of pressure. The thing with production is that you have strict deadlines because everything has to go on air at a specific time.

Now, that stress comes in a different form. I usually open the cafe on Friday, so before that, I have to prepare everything for all the guests. It’s tedious but fun.

For example, I have to cut the grass around the property. And with 10,000 square feet of land, that will take me three days.

The service standard here is also relatively high, so I have to ensure all the little things are done perfectly so that customers are happy. Chopsticks must have paper sleeves, the tables must be clean at all times, and you cannot leave used cutlery when the next guest sits and so on.

That’s the kind of stress I have to deal with, but at the same time, I’m enjoying nature all around. I get to eat fresh food here, and it’s much more relaxing than the documentary production system.

The Countryside and the City

For me, Singapore is stressful because it’s all city. Sure, we have natural reserves such as Chek Jawa and Sungei Buloh, but it’s not the same. I live 450 meters above sea level— when I open my door, I immediately see a mountain.

The other nice thing about Japan is that people respect privacy and human rights. No one will put you in jail if you say something against the government.

Here, the government will not do anything to you, and there’s almost complete freedom of speech. I say complete because there are some bad eggs here and there, but you feel free in Japan.

In Japan, no one pushes their opinion on you. For instance, no one passes remarks on another person’s farm. If you farm your way, it is your way. Nobody will tell you how to farm; they will just comment, “Oh, those crops look very nice.”

They don’t offer unsolicited advice either. Let’s say somebody is female-presenting. If they say, “I’m a woman”, the Japanese will say yeah, you’re a woman. No one judges you.

Never Going Back Home

At this point, I’m never going back to Singapore. Of course, I’m going to visit Singapore to see my friends and family. But after living in Japan for ten years, I don’t know how I can live in Singapore after experiencing all the countryside has to offer.

The cost of living is low, and the kind of stress I experience is different—it’s the type I like. I get to be outdoors anytime I want.

Another thing about living in rural Japan is in the event of an earthquake, and the pipes are broken, I don’t have to worry. I have a spring, and my neighbours have a natural stream piped in—there are multiple sources of natural water.

Last night, there was a loose dog in the neighbourhood. They called everyone to ask if our dogs were safe at home and to ensure everything was okay. That’s just the kind of community that we have in rural Japan.