All images by Shiva Bharathi Gupta, all videos by Stephanie Lee for RICE Media

We sit in eerie silence as colourful spotlights oscillate inside Club Hell. Brightly lit as it is, the whole scene looks like someone hit the mute button.

As the quiet grew, it became much more apparent that it was the dead of night. Not even the birds were awake.

The empty dance floor seems smaller, somehow—and colder. A stark contrast to how it looked just a couple of hours before when it was filled up from wall to wall.

But where one exuberant party ends, another one kicks off. And it begins with a couple of heavy-duty trash bags, a couple of detergent bottles, and a shot of can-do attitude.

Welcome to Hell

Club Hell is an LGBTQ+-friendly club relatively new on the scene. Opening its doors just last year on 16 December 2022, it rode the wave of revenge-partying right on the cusp of the revival of Singapore’s nightlife scene.

Telok Ayer is known for its nightlife. It’s where you’ll find upscale pubs, cocktail bars, and atas dining establishments. Tonight though, as my ride pulls up along Telok Ayer Street at 2 AM, the entire stretch is lined with closed shutters and locked doors.

There is only one venue still bustling with noise. An LED sign—flickering between ‘HELL: VACANCY’ and ‘HEAVEN: NO VACANCY’—blinks above a set of industrial rubber curtains.

But I’m neither here to party nor am I dressed for the occasion. I’m going into the depths of Hell to watch someone clean up the hot mess left behind after-after hours.

I get a sneak preview of the clean-up job at hand. Tired partygoers sit along the curb, puking their insides into roadside drains. Companions surround them, patting their backs while looking at their mobile phones to see if a Grab ride is ever going to come. Some of them are at the point where they won’t remember anything the next morning.

But unlike the club’s patrons who can afford to just go home and forget about it, every additional puke puddle is just one more thing on the list to clean for the Hell’s small team of part-timers.

Jack of All Trades

The club’s clean-up crew, as I’m about to find out, are far from what you would imagine them to look like.

Through a minimalistic arch in the wall next to the club’s entrance, donning a simple black tee and black pants, Ben greeted the RICE crew with a soft-spoken “Hey”. Like the white, boarded-up exterior design of the club, the 23-year-old looks inconspicuous.

Ben is one of the eight-man part-time crew who works at Hell every weekend.

“Club Hell is a local start-up. Unlike the bigger clubs which usually hire an external cleaning crew, we, as the in-house service crew, have to cover multiple roles,” says Ben.

By day, Ben is a full-time student. By night, he works at Hell. Unlike the usual nine-to-five that most are used to, his hours are, shall we say, ungodly. He reports to work at 9:30 PM on Friday and Saturday nights. His shifts last six to seven hours, until the club closes.

“I’m part of the floor crew, which means serving tables and drinks. I also seat the VIPs when they arrive. I stand in at the bar at times when needed to,” lists Ben.

Tonight, in particular, Ben is the cashier at the door. But no matter which job he’s assigned to for the night, it always ends with the most arduous task of all. Cleaning up after clubbers.

Cups, Cups, Cups

As the club’s last customers stream out the door before the clock strikes 4 AM, I watch as Ben and the rest of the crew get to work.

“Personally, the cleaning up part is my least favourite part of the job because patrons tend to leave cups everywhere. Sometimes it feels like I’m playing a game of hide and seek every night. They end up above cabinets, in the bathrooms, and sometimes on top of people’s cars by the road,” says Ben.

But cups are the least of his worries. Anything dry can be quickly swept up and thrown into the bin. 10 minutes in, the garbage bags are filled up and the club’s tables have been wiped down. Is that really all there is?

Then, we walk into the bathroom.

The Smell of Sulphur

It’s the smell that hits you first. A sour mix of puke, alcohol, and urine floods the enclosed space that unfortunately, because of how the building was designed, cannot be ventilated.

The moment I step in, the odour clogs my nose. Before I can venture further in, I immediately step back out. I take a second to let the smell clear out from my system before going back in again.

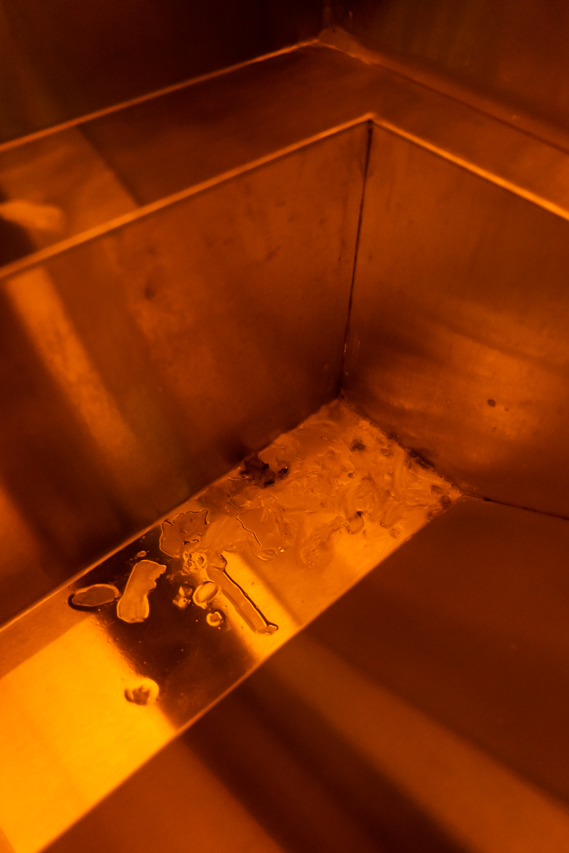

I peer into the sink to see vomit left around the drain. I involuntarily make a face.

Ben sees me grimacing. “This is considered good,” he says reassuringly.

“It’s bad when the puke is fresh, the sink is clogged and water can’t go through. It piles up.” I hold back my imagination.

He tells me that when it clogs, they have to use a plunger to unclog it before washing it all down with soap water. But he admits that he doesn’t speak from first-hand experience. He often leaves the task of clearing vomit to his colleagues.

“I can’t deal with puke, the sight of it makes me gag,” he admits.

You and me, same, I think. I avoid a closer look into the sink in case I unintentionally add to the chunder. We trudge on.

He pushes open the door of a cubicle and a new wave of stench assaults us. We’ve found the source of the stink.

Damp toilet paper litter the damp floor, trodden on and shredded. There is an unidentifiable stain on the outside of the toilet bowl. In another equally wet cubicle, a pair of stained underwear lies abandoned in the corner.

Lost and Found in Hell

Ben’s job extends beyond the four walls of the club. Sometimes, customers vomit at their neighbours’ doorsteps—as they do.

“We definitely don’t want to leave it for our neighbours, so we are responsible for cleaning that up too,” Ben says.

Washing it down the drain with water is an easy enough first step. But if that’s not sufficient, Ben tells me they use paper towels and a hard-bristle broom to sweep up the chunks.

“Every now and then, clothes get left behind. We get people removing their tops when they party—you will be surprised at the amount of expensive clothing we’ve found. To top it off, we found shoes left behind too.”

“How do you go home with a lost shoe?” Ben wonders out loud.

Tonight’s haul? A black button-down shirt. It’s drenched, either with sweat or alcohol or both.

He casually picks it up and takes it behind the bar, adding the shirt to the pile of lost and found items. They usually keep personal belongings for one to two weeks to wait if the owner claims it, before throwing them away.

Like a show-and-tell session, Ben picks up the items that people have left behind. He shows us a GrabPay card, a fanny pack, and some pairs of glasses.

“People leave a lot of valuables here. Their wallets, identification cards, credit cards, phones and watches too.”

Amidst the high-intensity partying to make up for the sober nights during COVID times, clubbers tend to drop valuable items like Airpods Pros and even their keys.

Ben and his colleagues understand this pent-up energy to make merry for Singapore’s LGBTQ+ youth. They have relatively lesser avenues to find their crowd in the local nightlife scene.

Ungodly Hours

The clean-up process, having been streamlined over the last three months, takes the crew 30 minutes to finish. On Saturdays, when his shift ends at 4:30 AM, Ben usually only goes to bed at 5:30 AM or 6 AM.

“Hell only operates on weekends, so I can sleep in on Saturdays and Sundays, until 11 AM. I’m quite a morning person.”

A strange sentiment from a person who works at a club. Plus, as a full-time student with classes from Monday to Friday, Ben’s schedule is already jam-packed.

He is currently retaking his O-Levels and spends five to six hours every weekday attending classes. After class, he heads down to Bugis National Library to continue studying for another two to four hours.

During other pockets of free time on the weekends, he goes to tuition, which takes up four hours a week.

“My friends always ask me how I do this every weekend, it sounds so tiring to them,” Ben says. His parents have also raised concerns about his sleep schedule—they want him to do well in school instead of spending his nights working.

But Ben seems to cruise along just fine. “The only challenge I’m facing right now is cramming for my examinations. Other than that, I’m doing alright,” he shrugs.

He took up the job originally just to earn some pocket money—he doesn’t rely on his parents for an allowance. He also hopes to fund himself in his pursuit of a diploma after finishing his O-Levels.

But it’s hard to find time to part-time when most of his week is taken up by academia.

A nightlife job was the only answer. But between Hell and another job at a regular bar, he chose Hell.

See You in Hell

“Working at Hell is really different from other clubs. It’s where the LGBTQ+ circle hangs out and the vibe is just different,” Ben explains.

“It makes me feel good that I’m able to support the community.”

“It’s so lively and I feel relaxed here. After the sun is down, this is where the party starts. People are more relaxed and more laidback—compared to how Singaporeans usually are in such a fast-paced society.”

The money is a bonus now. What keeps him going through the vomit, mysterious stains and sleep-deprived nights is the camaraderie he found with his colleagues and Hell’s regulars.

“Most of our VIPs are regulars and treat us nicely. When they offer us drinks it makes me feel really appreciated because they know it’s not an easy job working in this fast-paced environment.”

Although he admits that he doesn’t have much time to spend with his friends, Ben points out that he makes friends working at Hell as well. He tells me how there are no staff dramas and everyone’s friendly with each other. Even regular customers have turned into friends.

Overlooked, Overwhelmed

As a small club, Hell had to get by on its small team of part-timers. This was especially hard during the initial surge of patrons when it first opened its doors.

“All of us were overwhelmed by the crowd. COVID rules had just relaxed, so a lot of people were coming back into the clubbing scene. We were understaffed for the first few weeks.”

Thankfully though, the surge has since subsided and stabilised. Ben shares that it’s easier to manage now than before.

Nevertheless, it’s still a difficult job. After a long night of being on his feet and serving customers, he still has to get his hands dirty to get the club ready for the next time its doors open. He reaches home right before sunrise and sleeps six hours, only to wake up and do it all again.

But seeing the unglamorous side of clubs hasn’t put him off partying. On his off days, he will choose to come back to Hell as a customer. But having experienced what goes on behind the scenes, he says that he is more conscious of trying not to make a mess.

“Most people can tell you that they have clubbed before—but there are probably a handful who’ve properly worked at one. My advice to partygoers would be to be a bit more proactive, a bit more considerate,” he implores while clearing up a half-drunk bottle of champagne.

“I’m proud of my job. I know the pain, I know how much hard work we put in to make sure the crowd has a good time every time.”

Rarely are there young Singaporeans who are willing to clean up after people’s puke and shit and sweaty clothes. And yet, Ben tells me he plans to work at Hell as long as he can.

“To all the people who are working in the same industry as I am, I feel your pain. Mind over body, that’s what I always tell myself,” he declares.

“After all, we have to work as hard as we party.”