Top image courtesy of @sgacadboycott

To all the kids fearful of student protests overseas, remember we have student activists at home too.

Recently, the Students for Palestine collective took a walk to the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) and delivered letters against the newly proposed ‘Maintenance of Racial Harmony’ Bill which could clamp down on solidarity efforts with Palestine. While it was literally a stroll from an MRT station to MHA, it caused quite a stir amongst online commentators.

On one hand, they received vocal support on their Instagram pages. On the other, they faced extreme vitriol on forums like Reddit.

Much of the complaints weren’t really about students gaigai-ing to MHA. Rather, they were about the “bad precedent” the walk could set, which Shanmugam claimed would “inevitably lead to protests of a much more violent and intemperate nature”.

It sounds somewhat logical. If you let these rabble-rousing students express their dissent peacefully, who knows what havoc they’d wreak if they had the chance?

But if we take a step back to observe what actually happened, all these students did was post infographics and donation links online. They picnicked and read Palestinian poetry. Even during their most recent controversy, they walked quietly and dispersed after delivering the letters.

One wonders whether this is the “protests of a much more violent nature” that the public should be worried about. If our anxieties are unfounded, it ignores what these students are actually trying to accomplish.

As these students navigate the laws that govern our freedoms of speech, they’re finding ways to advocate sustainably in Singapore while trying to avoid trouble and eventually graduate. In other words, they’re leading the charge for a new wave of—arguably more Singaporean—activism here.

The Price of Activism

A common critique is that activism has no place in Singaporean schools. But a quick Google search would tell you that student protesters are, in large part, why we aren’t singing ‘God Save the Queen’.

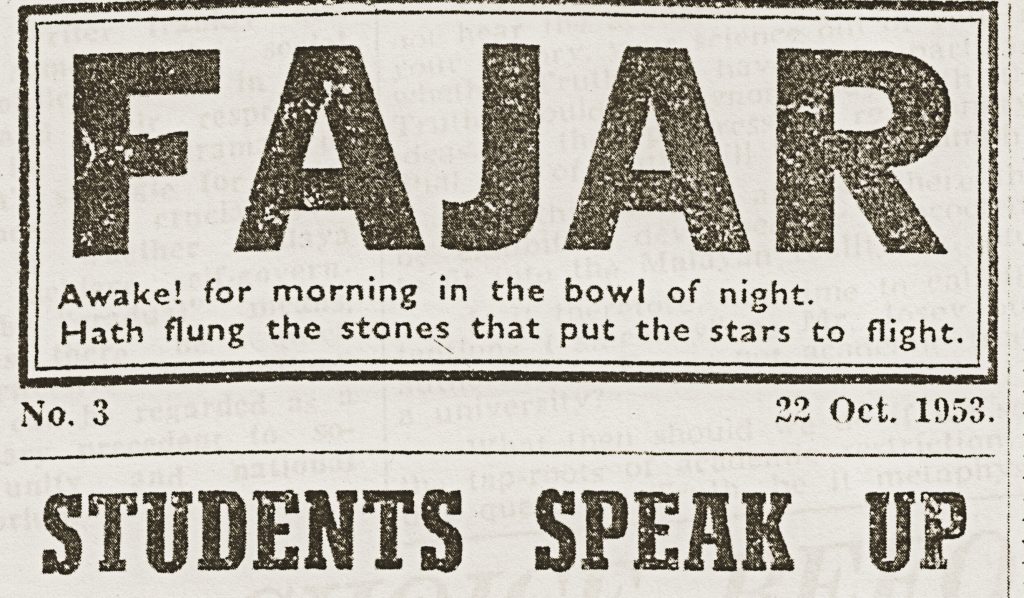

In the 1950s for instance, the University Socialist Club (USC) in the University of Malaya (present-day NUS!) played a significant role in establishing Singapore’s independence by speaking out against the British colonialists. After pissing the British off in their magazine, the Fajar, they were arrested and brought to trial.

Their junior counsel? Lee Kuan Yew.

Among prominent members of the USC were also future civil servants like S.R. Nathan and Tommy Koh. The Fajar trials put Lee Kuan Yew’s name out there, giving him the political capital to start the People’s Action Party (PAP). Even President Tharman admits he got his political start as a student activist.

Tracing our history reminds us of what activism is really about, especially for us as Singaporeans. It is also this history that continues to inspire and inform students today.

The Yale-NUS students who showed solidarity with Palestine during their convocation impressed upon me how interconnected their work is with the history of Singapore, laughingly dismissing the notion that they’re just emulating student protesters from the West. Much like the USC of the 1950s, they do this because it’s about seeing the potential in idealism and imagining a future outside of the status quo.

Yet, if many of our most established politicians got their start in student activism, why is it viewed so cynically today?

It has to do with the “high price for student activism”, notes Dr Kevin Tan, Adjunct Professor in Law at NUS. In the 1970s, the government detained and deported student activist leaders and amended university constitutions with the sole purpose of “depoliticising the student community and confining students to their studies”.

With these drastic shifts in our political context, we no longer see student activism as genuine political participation in Singapore. The apprehension from naysayers online reveals just how unfamiliar dissent is to us now, and how we might have lost sight of what student activism is about—advocating for social change that matters to the future of Singapore in an urgent fashion.

Ungraded Participation

What makes universities a hotspot for social activism in the first place? For some student activists, their campaigning is a natural extension of their education.

“You’re encouraged to ask critical questions and engage in civil discourse. Sometimes you’re even graded for that. It’s called participation,” Hannah* from NTU Divest quips.

The Yale-NUS students express the same deep appreciation for their education, telling me they believe it’s their responsibility to care for the world and each other. These activists want their education to amount to tangible change in the world.

At the moment, student activism covers a broad range of concerns, and they all reflect a desire to use the critical lenses they’ve learnt in class to create real systemic change in society. Some of the causes even tie in closely with their fields of study: one of the NTU Divest members I interviewed is an Environmental Science and Political Science major.

There are also many different kinds of change they’re campaigning for. NTU Divest is primarily concerned with climate justice. The Yale-NUS students and the inter-student coalition ‘Sgacadboycott’ care deeply for the humanitarian crisis in Gaza. There’s also NTU Financial Aid Friends and SUTD’s Somapah Hostelites who want universities to be accessible regardless of financial situation.

Often, interviewees would ask me who else I’d interviewed, referencing them by name and reminiscing about their friendships.

This interconnectedness within and between student bodies is also why students feel brave enough to mobilise. Lily* recounts how the support from the 40-odd students present kept her walking to MHA.

She was scared, of course. But with all her friends taking this risk together, she felt just how powerful collective action could be.

Adapting Activism

It’s easy to see our student activists as following trends from overseas. In one of his final interviews as prime minister, SM Lee criticised university students for following the spooky and scary Western phenomenon of ‘Wokeness’, leading to “extreme attitudes” in our youth. Lest we import too much Western wokeism till NUS resembles Harvard.

But, as Hannah explains, “Truth is you’ll see different strategies … (all student activists) have to work within the contexts of their own country.” They’re operating within the political realities of Singapore—advocacy within limits, if you will.

What works overseas doesn’t work in Singapore, Lily says.

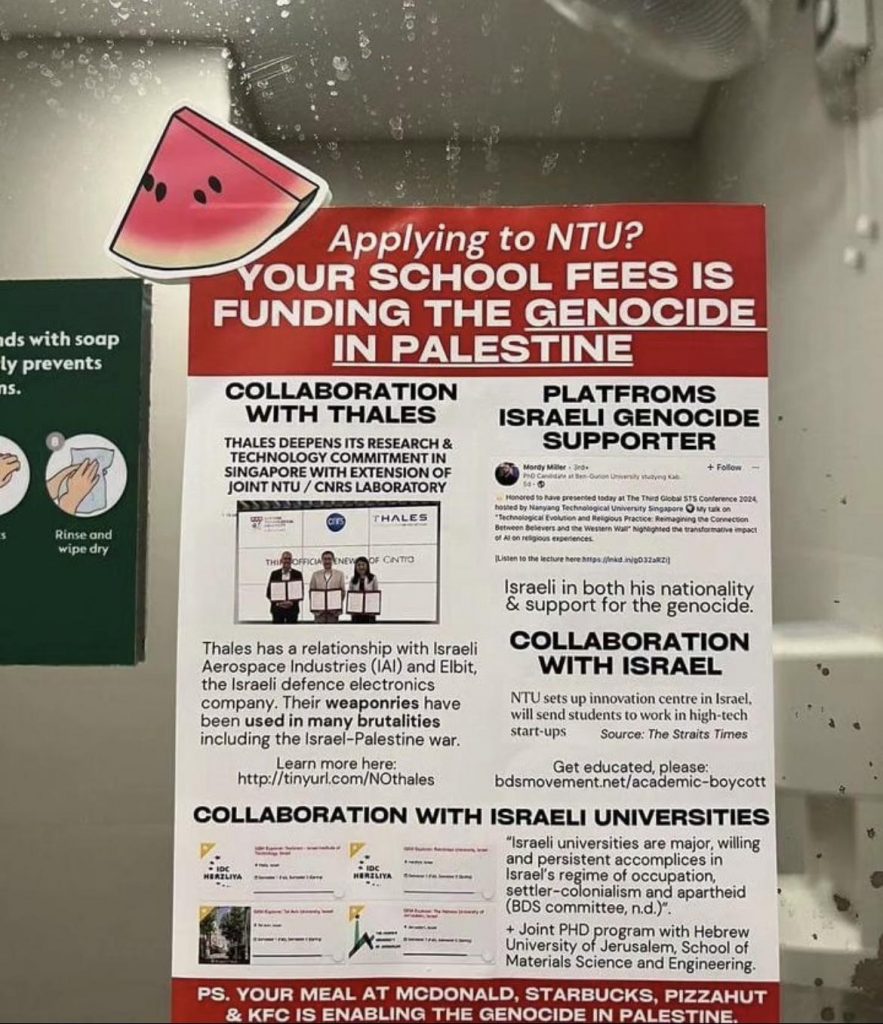

“There was a lot of backlash from a poster put up at the beginning of this year. It made us realise that students in Singapore aren’t used to hearing how they’re responsible for inequality or conflict as opposed to other universities overseas.”

In fact, a wholesale import of overseas methods wouldn’t work. As Terese from NTU Divest explains to me, they need to produce a unique brand of Singaporean activism.

One strategy is translating global conflict into something relevant for Singaporean audiences.

The Yale-NUS students tell me how their most effective forms of advocacy have been through encouraging students to care. By distributing flyers and providing a PayNow QR for donations, they were able to involve many students who were confronted with the extent of violence Palestinians face.

This approach has been successful in galvanising the public to care more about these issues, NTU Divest notes. “We live in Singapore and these are the cards we’re dealt.”

School censorship has always been a roadblock for student activists, but a generally apathetic student body can be even more limiting to their advocacy efforts. Student activists know this. They have to start from ground zero to educate their peers.

“The language of divestment is too aggressive for students here,” Terese laments. “We need to focus on empowering students to give a shit.”

This is, in large part, why students focus on social media to reach their younger audiences. They’re able to create materials that demystify terms like ‘boycott’ and ‘divestment’ and explain why the wider Singaporean public should care about certain issues.

Toeing the line

Sometimes, students eventually get tired of skirting around institutional censorship. They want to be heard—loudly and publicly. And that’s when we see them toe the line.

“We’re just done,” Lily tells me matter-of-factly. “We’re ready to face whatever we’re going to face.”

She reveals they’ve been investigated before, specifically for the ‘Steadfast for Palestine’ event. Their previous brushes with authority have made them wary, so they’ve “made preparations” when dealing with institutional backlash.

For one, they only sent in two representatives into the MHA building. When some of their members were investigated previously, they stood outside the police station in droves, waiting for their friend to be released.

They’re trying to create strategies to pressure authorities without breaking the law. And seeing how they’ve been investigated before, balancing lawfulness with urgent advocacy is still a work in progress for them. But as H tells me, it’s necessary to keep their activism viable in the long run.

The Yale-NUS students echo a similar sentiment. Institutional scrutiny has forced them to navigate a delicate balance between advocating for their causes and ensuring the safety of their events. They’ve faced censorship, direct suppression, and heightened security presence at even the most innocuous events like reading groups.

They tell me the fear of backlash wasn’t negligible when they were preparing for their convocation. But far more important was showing solidarity with Palestine especially in the face of impending scholasticide in Gaza. It’s why they wore ribbons in Palestinian colours and donned keffiyeh over their graduation gowns—a visible and powerful show of unity that still managed to preserve the safety of those involved.

“When the harm caused by institutions investing in oppressive systems goes unpunished, what does trouble truly mean?” they ask me.

But if they really wanted to make a change, why wouldn’t they leverage on pre-existing channels for feedback and advocacy? Instead of walking to MHA, why couldn’t they have talked to Shanmugam like the scores of other law abiding youth?

After all, universities do have existing cause-based groups, especially for more mainstream topics like environmental issues. When I asked if they’d ever considered joining these official groups for some form of official recognition, they sighed. Really loudly.

“I used to be part of another environmental group in NTU and it left me jaded. Once, I had to send a poster back and forth to the school 12 times just to get it approved. Another time, they even made me remove a rainbow from one of our graphics just because it had ‘LGBTQ’ implications,” Terese gripes.

I hear a sense of disillusionment from the students I speak to. Content policing is what depoliticises official advocacy groups in public universities, rendering them toothless. It’s a big reason why students switch from ‘official’ channels of advocacy to informal student activism.

Student and Activist

“The term ‘student activist’ often carries certain connotations, but in reality, we’re just regular students who care deeply about shaping a better future.”

Lily got visibly emotional when I asked what student activism meant to her.

“When my mum remarried, it looked on paper that my family could afford to send me to university when we actually couldn’t. I nearly couldn’t afford university. NTU Financial Aid Friends made it easier for me to access financial assistance. I can’t tell you how healing that’s been. I can literally change my life and remove what causes me and others so much pain.”

Her activism allowed her to continue her schooling, but it’s also something she fears will hinder her and her peers. “I kept thinking about my friends. They’re trying for scholarships and financial aid. What if it gets revoked because they (get in trouble for the walk)? It’s fucking scary.”

On one hand, their conviction compels them to challenge the system and fight for their causes. This fervour is highly visible; it’s why a lot of us think they’re idealistic. But as I spoke to them, I felt a palpable fear— either for their own safety or for the safety of others— which made them assess the risks of their advocacy.

It’s precisely this internal tension that makes their advocacy earnest yet careful.

But how does student activism fit into national civil discourse?

To policymakers, they’d much prefer the students (or any dissenting voice) meet them in “mutually respectful discussions”. They seem eager to make friends, after all. This approach is in line with PM Wong’s ‘Refresh PAP’ exercise, which is all about engaging oppositional voices within the party.

But the extent of our political participation cannot be reduced to complaining to the various governmental bodies. Just this month, we saw unhappiness across the board about how complaints to the government caused a Science Centre talk to get cancelled, or nearly took the cigarette out the hands of an illustrated Samsui woman.

Recent events are highlighting our growing concern for knee-jerk institutional censorship, or how the government sometimes bows to the pressure of loud complaining. It begs the question: is feedbacking to the government all we can do to make change?

Beneath the public controversies of student activism lies a growing appetite for advocacy that challenges institutions beyond traditional feedback channels. And as these students are attempting to prove, things can be done without jeopardising safety.

They’re also the best people to workshop activism. “If a group of workers did what we did at MHA, it wouldn’t have been as well received,” Lily admits. “There are other groups organising, but students get the most favourable response.”

Lily was so acutely aware of how students might have the best optics when doing something subversive, making her work all the more urgent and necessary while she’s still enrolled in university. In a Singaporean way, it was surprisingly realistic and, frankly, cynical.

While some might continue to dismiss student activism as naive and impractical, we forget these students are just as Singaporean as we are.

The only difference? They actually believe they can change something about Singapore, a belief many of us perhaps gave up as we got older and started adulting.

Advocacy in Singapore has been a steep learning curve—and a detrimental pursuit for many Singaporeans both past and present. But these students are figuring it out for future generations of conscious citizens.