All images by the author.

When my helper of 27 years left to go back home to Jakarta, we often spoke over the phone about seeing each other again. I had no idea it would end this way—me standing over her grave, looking down at the ground of what remained of her, my face streaming with tears.

The grave is uncared for. Trashed and forgotten. And this was after I had sent over money to her family to make it “good,” as Indonesians would say. But nothing here looks good.

As I dug my hands into the ground, yanking out weeds and picking up plastic bottles and trash, I never felt lonelier in my grief.

To the world, she’s my maid. But to me, she’s a mother.

In many countries in Southeast Asia like Singapore, Indonesia or the Philippines, we often hire helpers—or a maid as some would deign to call them—to care for our children.

The term ‘maid’ holds cultural connotations of colonialism. We hope that using the more palatable term ‘helper’ offers a clinical removal of such unsavoury overtones. We think changing the vocabulary may help us feel better about the exploitation of labour.

In truth, the word ‘helper’ wears a cloak of progressiveness without changing anything. They ‘help’ us. We pay them.

It’s all smoke and mirrors for a transaction that hasn’t changed in centuries.

I personally never thought of the word ‘maid’ as derogatory. To me, a maid is someone who worked alongside my mom to raise me. Someone I loved, who, when I was a kid, fed me and took care of me when I fell off my rollerblades and told me it was all going to be okay when I had my first teenage heartbreak. She taught me how to be resilient and strong and did all the dirty work my parents were unwilling to do when caring for me.

I sat and sobbed over the barren ground where she was buried. All I could think of was how this force of a woman was now dust in this cracked, dry, orange land.

How could I have left her like that for two years?

Loving the Help Wholeheartedly

It’s funny if you think about it—these women are essentially hired to be family members, participating in the act of raising other people’s children. Kids grow attached to them. At times, they see their helpers more often than they do their own parents.

Yet, at the same time, there is a transactionality to this relationship (surprising or not). They are paid to care for your kid. Your kid, being a kid, loves them blindly in return.

It’s a relationship fraught with both exploitation and intimacy. As a fully-grown woman raised by my helper, I still find this relationship difficult to digest and decipher.

Thinking back, I remember giving her hugs and affection and saying, “Sorry Endang. Maaf ya. Tadi saya marah…” after losing my temper at her for ironing my clothes wrong or messing something trivial up.

I remember when she cooked a fantastic nasi tumpeng for my birthday party. As my friends dug in, she sat at the back of the kitchen, doing her duties instead of joining in.

I used to pray to God that she would never have to leave. My biggest fear back then was that she would have to go back to her real family.

Even in navigating this unbalanced mother-daughter/employer-helper relationship, there was inexplicable authentic, unconditional love for each other.

Still, for our parents, this transaction is viewed differently. I’ve seen how my friend’s parents reacted to my friend wanting to give her helper a heartfelt gift—a framed picture of the two of them—when she was retiring and going back to the Philippines.

“Why? We already gave her a lot (of money). We don’t need to give more,” they intoned, incredulous that their daughter felt she needed to give the helper anything else. For them, it was all a mere business transaction.

Helpers Seen and Lost

The revolving door of helpers and drivers coming and going from my family is ever-turning. I remember a company driver I spent time road-tripping with in Batam, only to find out he died a couple of years later in a car crash.

I’ve also seen my cousins grow up with the same helper for decades. The years have been unkind as we watch her wither away in age, to the point she could no longer work and was sent back. Their helper has since passed away as well.

I have always wondered what this relationship meant to the different parties involved. Is it just helper-employer? Is it a friendship?

For me, it was a familial love and bond. And it can go both ways.

When my grandfather died, I remember having to shake hands with countless funeral attendees. Everyone who was family wore a pinned rose. So did I. Looking around, I saw the helpers who took care of him, rose-less, eyes red from grieving for the 99-year-old man they spent every waking day taking care of.

Standing surrounded by hundreds of flower bouquets, I watched as the helpers mourned my late grandfather. But at least there was a ritual and a space for me to express my grief.

But when my helper died, all I got was a picture sent over WhatsApp of her lifeless body wrapped in a kain kafan (the white shroud used in Muslim funeral rituals) and a phone call revealing that she had passed away.

I sat in my room alone in deafening silence, with no one to mourn with. No hands to shake, nothing.

I longed to be there for her funeral, but it was 2020—the height of the pandemic. Still, that didn’t stop me from clicking furiously on my phone, searching for flights despite knowing there were none.

So in the middle of this helpless night, with a giant void in my heart and a rock in my throat, I did the only thing I could do—the superficial act of arranging for flowers at 2 AM.

If I couldn’t be there, a stand of flowers would have to be my stand-in.

The next day, I was sent a picture of the flowers at the funeral site. The image was strange. One floral arrangement on a barren field, plastic chairs in the background, no other bouquets around in sight. Mine was the only arrangement she received.

I loved the woman like my mother, and all I had for her was some flowers in an empty field. To me, she deserved the world—she deserved thousands of flowers and an ocean of love surrounding her. She deserved to know how much I valued her.

All this love I had for her had no place to go.

The Career of Care

It made me wonder how different my life would have been without her—how she forms an integral part of who I am today. Like my helper, many domestic workers stay with their families for years in regions like Singapore, India, Malaysia, Hong Kong, and Indonesia.

I grew up observing maids enter the lives of affluent families and observed this relationship until their employment ended. The person they cared for either didn’t need them anymore or died. Either that or the helpers themselves fell ill or grew too old to work.

In the case of my helper, it was age that led her to spend her golden years back in Jakarta with her family.

In Singapore, helpers’ contracts are typically renewable for two-year terms. Worker retention is encouraged to prevent excessive turnover. Workers must be 23 to 50 years old during the age of application; they can renew their contracts and stay for an unlimited amount of years until they reach the age of 60.

However, I know things are different from personal experience after helping my mom send in appeals to the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) to enable our helper to stay longer. You can retain a helper beyond that age in Singapore. My helper stayed with us well into her 60s.

Hong Kong bears a resemblance to Singapore, with similar renewable two-year contract terms and an age range of 18 to 59, with one considerable difference. Hong Kong implements a long service payment for domestic workers who have been with their employees for more than five years and are retiring due to health issues or old age.

There, helpers who have had their contract terminated due to redundancy—such as a move or the fact that the children your worker is taking care of have grown up—still get a service payment.

In other regions like Indonesia, the household is considered almost always off-limits with regard to state intervention, meaning laws regulating helpers have been left largely unregulated. The role of domestic workers is seen as a maternal one, and they are often referred to simply as helpers (the soft term in Malay: pembantu) rather than perceived as actual workers.

They do the work of worker without the protection of regulations; they play the role of a maternal family member, without the privileges of being one.

After two decades of pressure, Indonesia is still working on passing a domestic workers’ bill. Their exclusion from labour law gives them little to no control over the terms of their employment and little structure to implement a pension plan.

Similarly, in the Philippines, being a domestic worker (‘kasambahay’ or ‘yaya’) is considered neither a formal nor an informal occupation. Paid domestic work is an essential source of employment, with numbers increasing yearly. However, many people regard it as unskilled work that can be exploited.

The implementation of Kasambahay Law in 2013 offers more protection for Filipino domestic workers—but it has opened the door to unethical practices by unscrupulous employment agencies charging illegal fees and offering little stability. Many workers are afraid to voice any complaints and remain vulnerable to the hands they are dealt.

Helpers work well into and beyond their retirement years, dedicating their lives to other families as an occupation, partly because of the lack of security that their job offers them. Informal work arrangements mean little political protection and practically zero financial cushioning after retirement.

With many countries not offering any pension, there is little security for what comes after. And for those without children or families to take care of them, what sort of life are they returning to?

Then there is the emotional impact of living a large portion of their life embedded in someone else’s home.

One party watches the other grow up. The other watches the other age into their autumn years.

Grief With Nowhere to Go

Finding a place for the love I had for my helper after she passed on was like navigating in the dark in an empty room. Especially since she wasn’t technically my family or my friend. I had no one to share this grief with—and hardly any place to visit to bear witness to it.

When I confided to my mother about my grief, she retorted with hurt. “It feels like you loved Endang more than me,” she remarked.

This is not the first occurrence of a parent feeling slighted by a child’s love for the helper. Nor will it be the last.

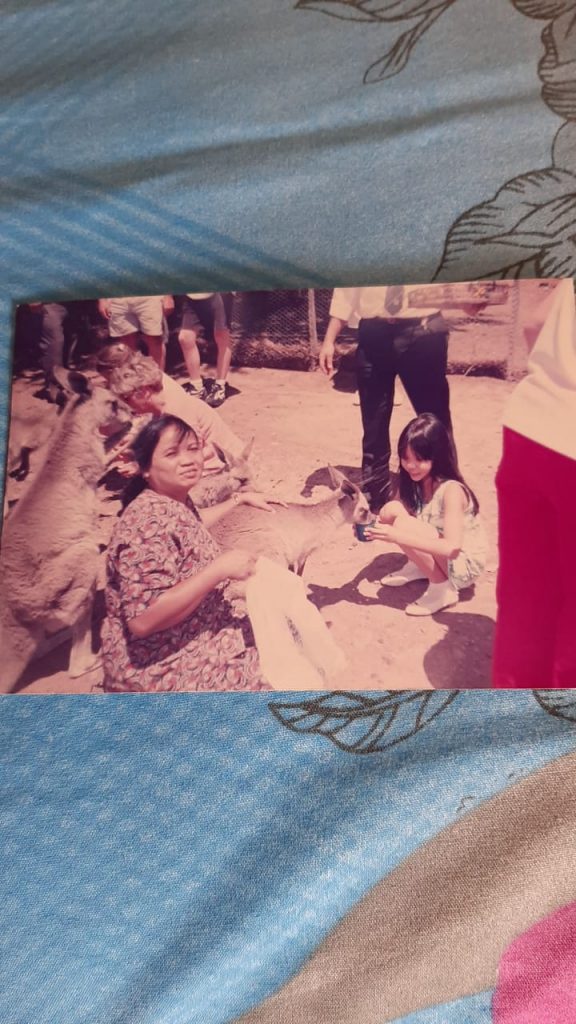

As people from an invisible faction of society, helpers are often kept in the background or sidelines of our lives. They are the ones in the corner pew of a grandfather’s funeral. They are the ones cooking in the back of the kitchen on our birthdays. They are the ones holding the camera and snapping our family pictures on holidays and occasions—rarely a part of the photo.

Most of the time, they are unseen and unacknowledged. And so I found my loss and love similarly unseen and unacknowledged by society.

A Fitting Goodbye

After leaving Jakarta, I offered money to ensure my helper got her final resting place. I only received a picture of the completed work while in the throes of writing this piece.

And yes, I know ceremonies and tombstones are more for the living than the dead. But it’s finally a worthy space where she can be honoured in the way I feel she deserves.

More selfishly, it’s a way to hold on to the little I have left of her.

The groundskeeper is also working on getting a tree planted next to the tombstone. During my visit, I noticed that the other side of the graveyard was sprawling with beautiful trees, and I knew I wanted the same for her.

They offered frangipani, which I gladly agreed to. I didn’t even know that frangipani is both a fitting symbol of the immense love and lasting bond between two people—and also a symbol of connecting with spirits and ghosts.

That’s all I ever wanted. An expression of love for Endang and a way to connect to her again.

So often, helpers bear the burden of domestic labour and mothering. But they are ironically never really considered truly part of the domicile. They spend years mothering children but are never considered part of the family. They spend years in our personal space but are never really at home.

But Endang was my family. And I hope that now, she has finally found the home she truly deserves.