Top image: RDNE stock project / Pexels

At the last wedding I attended, I was handed one of the most stressful tasks: Ang Bao keeper. As guests streamed in, I was supposed to greet them and collect their ang baos in an auspicious red bag.

If you know anything about Chinese people, it’s that they go big on wedding ang baos. I probably had tens of thousands of dollars in that one paper bag. I was Jason Statham in Transporter, tasked to protect precious cargo with my life.

Besides (god forbid) not losing the bag, the crucial part of the job involves making sure guests’ names are written on the back of the red packets.

I feel the need to clarify that the couple weren’t being calculative—they just wanted to make sure all the red packets were accounted for (ang bao thieves and all). But there are other couples out there who tally ang baos for a more pragmatic reason: to keep track of how much each guest gives them.

Some even go to the extent of asking guests to identify their ang bao after the wedding. Others think it’s kosher to reach out to a friend to demand ask for their ‘missing’ ang bao.

I’ve also heard of couples taking note of who low-balled them and vindictively pulling the same stunt when it comes time to attend the latter’s wedding.

Beyond weddings, parents often ask kids to ‘report’ how much they receive from uncles and aunts so that they can give out the same amount. Essentially, if you give my kid $20 ang bao, your kid’s also going to get $20 from me—no more, no less.

Thankfully, I’m not married yet, so my coffers still see a net gain every Chinese New Year. But with more and more of my friends tying the knot, I‘m feeling the pinch.

As much as it sucks to say, my first thought upon receiving a wedding invitation isn’t unbridled joy. It’s now “Can I afford this?”

Have we gone too far? There are now so many rules around ang baos that they’re beginning to feel more like a burden when you have to fork out oodles of cash to maintain relationships with friends and family.

Money No Enough

In discussing ang baos, we need to examine Chinese culture and how money-obsessed it is.

Flashback to roughly 3,000 years ago. The Chinese were one of the first to use coins as currency. That is to say that money has been a huge part of Chinese society and culture for a long, long time—abundance, wealth, and prosperity are ideals that date back to ancient agricultural societies in China.

Even when China moved on to the industrial era, it still held similar ideals. “To get rich is glorious,” as Mao Zedong’s successor Deng Xiaoping once said. And it’s safe to say that Chinese people’s penchant for accumulating money has stayed strong to this day. Just look at the chokehold Chinese e-commerce has on the world.

Malaysian comedian Ronny Chieng probably sums up the ridiculousness of our over-the-top love for money best. In his Netflix special Asian Comedian Destroys America, he says, “Chinese people love money so much, we have a god of money… Every day we go, ‘Hey god of money, give us more money.’”

This love for money is pretty universally Chinese and holds true even for the Chinese diaspora who’ve settled in different countries. We still greet each other with ‘gong xi fa cai’ every Chinese New Year, which is pretty much “wishing you wealth”.

We Chinese people are pragmatic. Why get the wedding couple a blender they might not even use when you can give them cold hard cash? After all, who doesn’t love money?

What started as a gesture of good luck to ward off supposed demons, however, has developed into a culture of its own full of unspoken rules.

In Singapore, online guides on wedding ang bao ‘market rates’ are pushed out annually, such is the demand for information. Even when Zoom weddings became a thing during the pandemic, Singaporeans scrambled for new guides and took to online forums for advice. What’s the ‘market rate’ for a wedding that you can attend in boxers?

All this goes to show how we have an urgent need to know how to avoid one of the biggest faux pas in Chinese culture: Stiffing a friend or family member out of a wedding ang bao.

The proliferation of these guides only popularises the idea of there being a minimum amount to give. Given how common these guides are (and how few wedding venues there are here), not knowing the ‘market rate’ isn’t a valid excuse, and packing an ang bao below the prevailing rate can be seen by some as an intentional slight.

Guides also exist for Chinese New Year ang baos. Financial platform Seedly recommends giving migrant workers you might meet in public $6 to $8. Cousins, nieces and nephews should get around $10 to $28 (the Seedly writer advises: “They are not immediate family members, therefore can be given lower ang bao amounts.”) Parents should get between $288 and $888 (because filial piety).

As tempting as it is to act like I’m above it all, I have to admit that I’m part of the problem. The first time I received a generous CNY ang bao from the parents of a guy I was dating, I scrambled to text my parents to stuff a little more cash into his ang bao they were going to give him.

Even though my parents weren’t as well off as his, I feared that giving him too small an ang bao could make our family seem stingy.

Don’t Count Your Ang Pows Before the Wedding

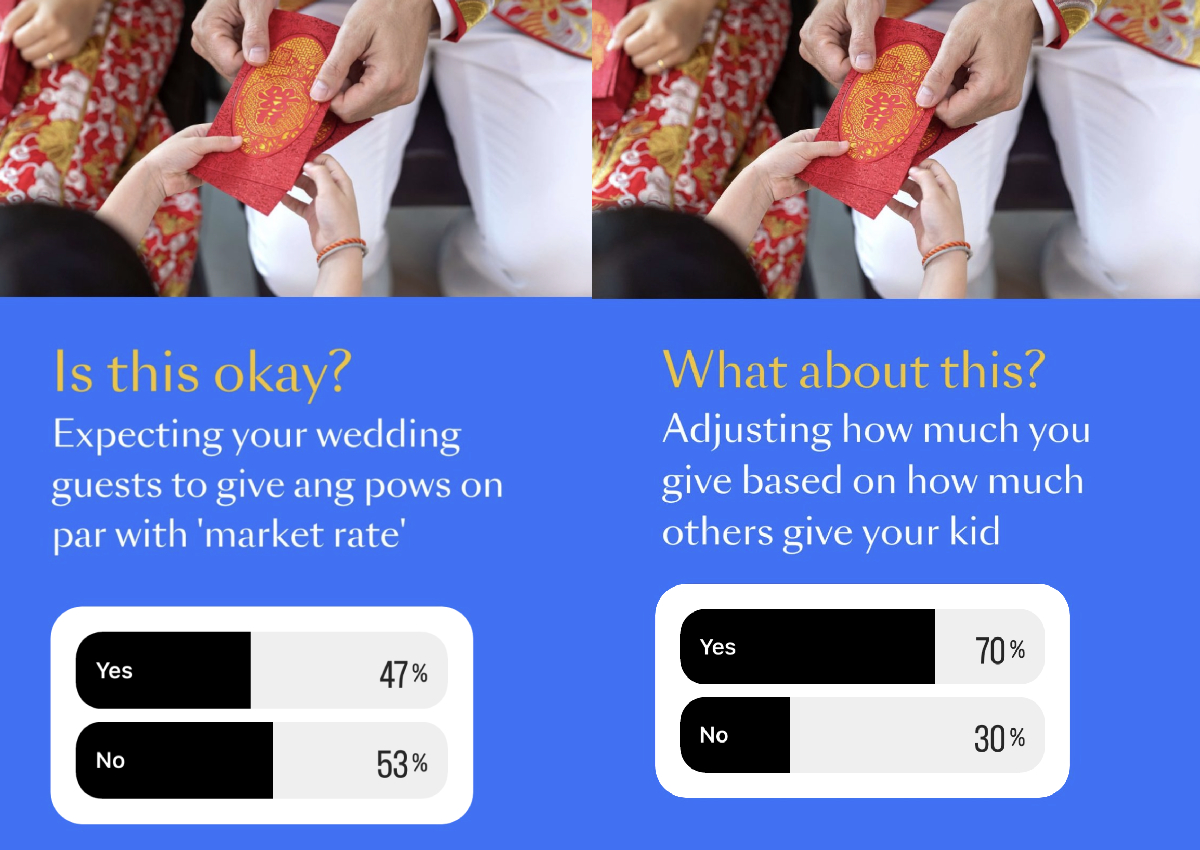

It appears that my concerns aren’t unique. An informal poll by RICE indicate that 70 percent of 226 respondents feel that using the amount given to your kid as a benchmark for your ang baos is okay.

What most people appear to have a gripe with: When ang bao receivers feel entitled to receive a certain amount. 53 percent of 217 respondents disagreed with expecting wedding guests to give ang baos on par with the ‘market rate’.

Tammy, a 46-year-old who wants to be identified by just her first name, says she’s so put off by ang bao culture that she’s actually chosen to skip CNY visitations in recent years. She’s still single but has stopped receiving ang baos (some Chinese families follow the custom of only giving ang baos to the young and unmarried).

“People start becoming entitled to expect certain amounts. Some givers also start feeling proud for being able to give certain amounts.”

She “just can’t afford” to peg her ang baos to market rate, she says, and chooses to give from her heart instead on the rare occasions she does have to give one.

Bruce King, who’s in his mid-30s, is another ang bao receiver who noticed a toxic shift in ang bao culture alongside mounting pressures in the cost of living. In the last 10 years, ang baos have become part of a cultural “rule” rather than gifts with no strings attached, he’s observed. Rather than being grateful for any ang baos they receive, people are judging the amount and the giver.

“Failing to give out red packets or packing too little money in it would lead to a negative impression of that relative, like they’re bad hosts, since it’s not like they’re poor or unemployed,” he says.

“It’s beginning to seem as if we value money more than family or relationships, where the latter is also highly valued in our culture.”

Like Tammy and Bruce, a good majority of poll respondents share the same sentiments. Most seem frustrated with how capitalistic ang bao culture has become and hope for a return to a simpler era—a time when we never needed market-rate guides.

”Giving is from the heart and should not depend on how much others give my kids,” says one poll respondent.

Another says she made it a point to tell her niece that it’s not okay to demand ang baos. Instead, one should think of them as blessings.

Unfortunately, ang baos aren’t immune to inflation. The ‘market price’ rises every year (hence the need for annual guides). This year, we’re looking at a 10 to 20 percent jump. It’s essentially becoming increasingly unaffordable to maintain relationships with our friends and families. And to what end?

The growing distaste for ang bao culture might even be a post-pandemic phenomenon. We got used to solitude—or at least, we had to pare our social circles down to the five or 10 people we were closest to.

Now that everyone else in our lives has come out of the woodwork, it’s natural to reexamine whether people are really ‘worth it’.

When Social Gatherings Cost More Than They’re Worth

It seems almost dystopian to view relationships in dollar terms.

When our monthly budget gets tighter, we start looking at the personal expenses we can cut. It’s a lot harder to be generous with others, especially if they aren’t close to us. And when people act like they’re entitled to our hard-earned money, it’s doubly frustrating.

Ang baos are great, don’t get me wrong. They’re the most practical gift out there. But expecting gifts and judging people based on the amount they give is just tacky.

Bruce has a theory.

“I think nothing is wrong with the concept of red packets. We can continue with it. It’s the people’s mindset that has become toxic because of the stressful and expensive environment we live in. The fixation on money is getting stronger every day.”

He’s onto something. Singaporeans aren’t the only ones with the same issue. Hong Kong has long been labelled materialistic and money-minded. The parallels are clear: both are hyper-competitive cities with high costs of living.

To play the devil’s advocate, it is hard not to become transactional when you struggle to scrounge together $200 for someone’s wedding, and they don’t return the favour.

But these expectations only drive vicious cycles. One poll respondent opines: “Wedding ang bao culture is the reason why venues can keep raising prices.”

Knowing how expensive weddings are, guests try to defray the costs with fatter ang baos. But is that really sustainable when costs rise year after year? Couples continue choosing fancy venues knowing that they’ll recoup at least a portion of their banquet cost. Others plan their guest list carefully to maximise profit. Yes, some people do earn money from their wedding.

This whole thing can be hard for people who aren’t Chinese to wrap their heads around. As a Chinese person, I remember attending my first Malay wedding and being shocked at how low the ‘market rate’ was ($20 to $50 seems to be the general range). Conversely, for those of other races attending a Chinese wedding for the first time, the steep ang bao rates would probably come as a rude shock.

SGAG personality Syafiqa Noor also touched on the topic in a TikTok, where she asked some real questions. “I ask [wedding guests] to celebrate with us, so why must they pay?”

She points out that while Chinese guests are considerate of the couple, Malay couples are considerate of their guests.

It’s hard to see how we can change things if a good number of people still subscribe to toxic ang bao culture. Short of refusing to partake in ang bao culture like Tammy, there really isn’t much we can do.

Skipping gatherings or weddings can harm relationships. As does giving an ang bao that’s too small. How do we even communicate to someone that our ang bao is small because that’s all we can afford or want to give? This is especially true when kinship is tied closely to ang bao amount (the closer you are to someone, the more you are supposed to give).

I do think one thing people can do—and I plan to do this when I eventually get married—is make it clear to guests that ang baos aren’t mandatory, nor is there any minimum amount. But knowing my parents and my partner’s parents, they’ll probably just try to give us even more in their ang baos to ‘make up’ for any ang baos we lose out on (in their eyes).

While self-reliance and not imposing on others are important to many people in my generation, it’s hard to change traditional mindsets where you invite your entire family tree and their dogs to your wedding and expect everyone to chip in.

Who Really Wins?

Perhaps, as a millennial, I’m personally getting more and more tired of ang bao culture because I’m pinching pennies and trying to save for a home. After all, one wedding ang bao can essentially pay for an entire month’s groceries for most of us.

But I’m sure others are feeling the pinch as well. As much as the government tries to rubbish studies that claim Singapore is one of the most expensive cities, things are hardly affordable here. When ang bao ‘market rates’ rise faster than inflation rates and our wages, people naturally feel disgruntled.

That’s not to say that Singaporeans are calculative scrooges. Any time a cause tugs at the heartstrings, we show up. The public raised some $2.9 million for a sick baby who needed an expensive drug. When a migrant worker died in a worksite collapse in Tanjong Pagar, 85 people reached out to his family to help them out (NGOs had to stop referring people to the family because they quickly received enough donations to tide them over).

We’ve also tapped into our pockets for overseas crises such as the conflict in Gaza, earthquakes in Japan, and the 2018 tsunami in Indonesia.

Perhaps it’s not that simple when it comes to the people in our personal periphery. An ang bao becomes a barometer to measure generosity and how close you are to a person.

We expect the people in our lives to show up for us. For some, turning up at their wedding is good enough. For others, it means subsidising it.

Don’t get me wrong. I love that Chinese culture prizes reciprocity. There’s an idiom—li shang wang lai— that roughly translates to “to return presents with presents”. We pay back a compliment with more compliments. We never call upon someone’s home empty-handed. Freeloaders are looked down upon.

It becomes exhausting, however, when we get obsessed over balancing the books with our friends and family. It’s not enough to exchange ang baos. We have to make sure there’s ‘enough’ in them. This is what’s destroying our culture of giving.

We have to stop and consider what we’re really doing all this for. For all the stress and toxicity, what’s the ultimate outcome? If we’re giving fat ang baos in order to offset the cost of each other’s weddings, the only real winner is the wedding industry.

We’re all planning expensive weddings with the expectation that our guests will defray the costs. As guests, we see it as our duty to defray the costs because, well, weddings can be expensive. Every year, vendors hike the prices up because they can.

It’s no wonder that elopements are becoming more of a thing for those who keep their weddings intimate and free of all these obligations. But it probably won’t be long before we get Wedding Ang Bao Rates 2024 – The Elopement Edition.