Top image: Isaiah Chua / RICE File Photo

When my parents made their first foray into F&B and set up their Penang restaurant along Thomson Road some 12 years ago, it opened to huge fanfare. Within my family, at least.

As a family of five, we crowded around our dusty old desktop computer in the living room, debating on the design of our signboard. Were sharp or rounded edges better? Emerald green or pine green? Plain red background or Peranakan motifs?

My brothers and I, still in secondary school then, were dispatched to the exits of a nearby MRT station to give out flyers. We beckoned strangers to give our char kway teow, prawn noodles, and assam laksa a try.

The restaurant quickly became a second home for us. I was—and still am—very much an introvert, so I busied myself with wiping cutlery dry and keying orders into the cash register. My younger brother, on the other hand, promptly made friends with the chefs and learned to fry up a mean plate of char kway teow.

My elder brother was too cool to associate himself with any of this.

News of the restaurant opening even reached our relatives in Malaysia—both my parents were born and raised there—who made it a point to drop by whenever they were in town.

Going Belly Up

We didn’t have to do much marketing. Word about our food slowly began to spread, and features in 8 Days and other food blogs brought us a steady stream of customers. The restaurant built up a pool of regular customers, many of whom my parents befriended. We were even on track to breaking even.

The highs of the restaurant’s early days came in stark contrast to its muted closure some two years later. I hardly remember it.

It was a fait accompli. The premises where we were renting underwent an en bloc sale, and we simply didn’t have the capital to set up shop again elsewhere. It was a good run. That was that.

The closure made us restless. With the decision largely out of our hands, there was a nagging sense of something left unfinished.

But it wasn’t all bad. For my parents, I imagine it was like the end of a marathon. Finally, a proper break after two years of slogging.

Even now, though, when I pass by the spot where our restaurant used to be (a regular occurrence since it’s not too far from home) I still think of what could have been.

As much as it was defining moment in my adolescence, it’s not that uncommon of an experience for F&B vendors to go out of business. Some closures, like those of Tiong Bahru Yi Sheng Hokkien Mee, Fosters Steakhouse, and Tian Tian Porridge make headlines.

Even more—like my family’s—go unnoticed.

Publicly available statistics on F&B business closures in Singapore are scant. But what we do know is that from December 2019 to June 2021, 3,440 F&B establishments shut down. And in a ‘when one door closes another opens’ moment, in that same period, 5,620 more sprouted up. How many are still operating today, I’m not sure.

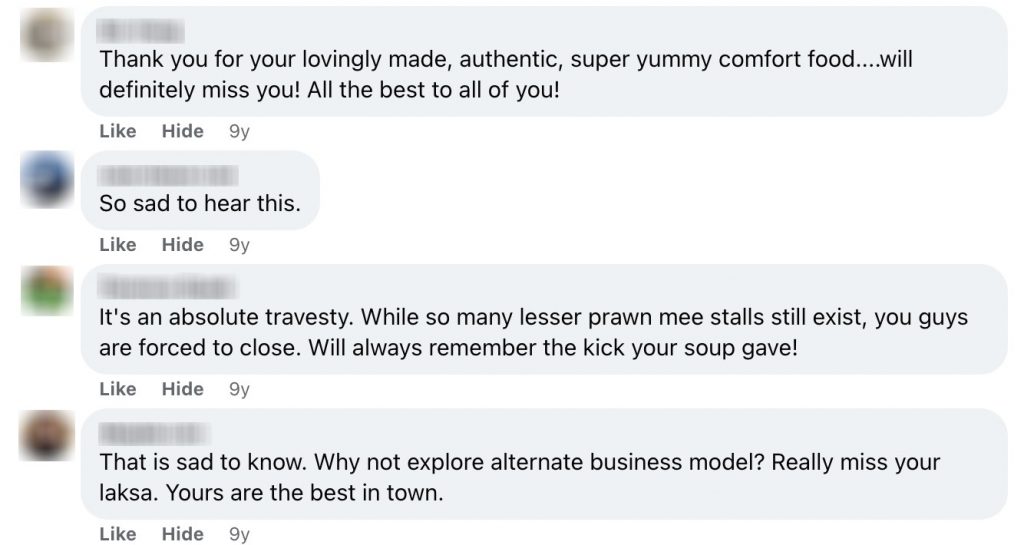

Not every closure hits the news, so some foodies make it their mission to update fellow foodie pals on the latest happenings in Facebook groups like Can Eat! Hawker Food and Hawkers United – Dabao 2020. Even before the closure notices become official, you’ll get the scoop from these online groups.

It typically goes like this: A regular customer teases the closure of a beloved F&B establishment, citing exclusive tea from the boss, deprived foodies swarm the comments section to pay tribute to the stall, ungodly queues form at said establishment.

Then the stall closes, gone but not forgotten in the hearts of local food lovers. Wash, rinse, repeat.

Some establishments go out with a bang—see Golden Mile Complex—but my family definitely wasn’t in the mood to party when we had to shutter our restaurant. Instead, we waited till after the closure to announce it on our now-defunct Facebook page.

A Hawker Two for Two

You’d think it gets easier with experience, but the bittersweet feelings stay the same.

Our second family F&B business was a dessert stall in the heart of Little India that similarly survived for two years before biting the dust last month. This time around, it was out of necessity.

My younger brother, 27, and homemaker mum, 66, started the stall not as a side hustle, but as a main source of income. A health scare meant it wouldn’t be safe for my cabby dad to get behind the wheel. We fell back to what we knew—food.

The new stall’s mainstay was Penang-style cendol, featuring pandan jelly and gula Melaka made from scratch by my mum.

Unfortunately, dessert just didn’t have a huge profit margin—the stall struggled to even make a couple thousand dollars in a typical month—and we didn’t have the manpower to venture into cooked foods.

And even though hours of effort went into our desserts, and they weren’t cheap to whip up, we had to keep prices below $3 the only way we could. The average hawker centre-goer likely wouldn’t spend more than that for dessert.

Throw in the unpredictable changes in dine-in regulations to the mix in our first year of operations in 2020, and the writing was on the wall long before my brother made the call to close the stall last month and find a full-time job.

He had already been laying the groundwork for the transition by taking online courses for months. Today, he’s working in cyber security, and is “definitely earning more” than in his hawker days, he tells me. He doesn’t rule out an F&B comeback, though.

It’s not hubris. The love for Penang cuisine runs deep in our blood, coupled with the frustration of not finding good Penang food that really hits the spot here in Singapore. (My email is below if anyone has any recommendations to share.)

What’s certain, though, he says, is that his hawker stint rid him of the naivete that hard work is all it takes to succeed.

I don’t know if the thousands of other stalls that have ceased operations can attest to just how hard it is to thrive in the F&B industry. But Jason Chua, the founder of the now-defunct restaurant Beng Who Cooks, can commiserate.

Of Rest and Relaxation

When I meet the 30-year-old for a chat at a McDonald’s near his home, it’s been roughly five months since the closure of his fusion omakase joint on Neil Road.

Jason, the eponymous founder of Beng Who Cooks, started the brand in 2018 as a hawker stall in Hong Lim Market & Food Centre selling protein bowls.

Together with then-business partner Hung Zhen Long, Jason made a name for himself after making the bold decision to give out free food during the circuit breaker period.

Describing himself as “very ambitious”, he eventually shuttered the hawker stall in order to chase his restaurateur dreams in November 2020.

Like us, he was dogged by the dine-in restrictions which were constantly in flux, on top of a sudden drop in footfall after a large company nearby relocated. But the last straw came when his landlord tried to raise the rent to the tune of an additional $5,000 per month.

There was simply no room for negotiation, so it was a foregone conclusion—the business could not go on. It closed in mid-October last year, ending on a festive note with a party.

Breaking Toxic Work Habits

For Jason, the closure came at a good time. Then a new dad, he was overworked and burnt out, with barely enough time to spend with his family.

Zhen Long had left the restaurant in January 2022, and Jason had been running it as a one-man show.

Zhen Long tells HungryGoWhere that his undoing back in Beng Who Cooks was “working too much day in, day out”.

And to his credit, Jason tells me that he could have been a better partner to Zhen Long, what with his intense working style and straight-talking ways, and doesn’t blame him for leaving.

Zhen Long’s departure, however, did mean a heavier load on Jason’s shoulders. Everything from cooking to backend operations was under his purview.

Jason recalls that barely three days after his son’s birth, he was back at the restaurant to “clear shit”. As the only full-time staff leading a team of part-timers, paternity leave was a luxury he didn’t have back then.

It’s much better now. These days, while his wife heads off to work as a teacher, he gets to enjoy some father-son bonding time.

During this much-needed break, he’s also been forced to slow down and reflect on things. He’d built a reputation for being brash and loud-mouthed—not surprising given his proclivity to lean into the beng persona—but it did rub some people the wrong way.

In a rare vulnerable moment, Jason says he’s seeking help for his mental health and has seen a therapist.

“To be honest, I was screaming for help internally, but everybody just saw me as angry. So I changed a lot after I isolated myself,” says Jason, who adds that he’s since become more mature and learned patience.

This means doing things step by step rather than doing “five things at once”.

Taking a break from hustling also allowed him to see that he had been abusing himself. For the old Jason, 16-hour workdays were the norm. Sleep was a waste of time.

The former competitive boxer puts it this way: “If you’ve got seven days, I’ve probably got eight.”

Taking a Break Is Expensive

Despite all the soul-searching and family time Jason’s enjoyed, the past five months post-closure hasn’t exactly been a leisurely holiday.

He’s been hustling, albeit at a slower pace, working part-time as a boxing instructor and selling his culinary creations via TikTok.

Describing himself as “downright broke” after losing the restaurant, Jason says he’s been limiting himself to spending just $3 a day.

“Men will be men. Maybe it’s just me, but my ego was very affected,” Jason admits. “During this time, my BTO (Build-To-Order flat) came, my renovation came, my baby came. Everything came—not the wrong time—but together.”

In fact, the McCafe Himalayan tea he’s sipping on as we speak has busted his budget for the day, he tells me. I instantly feel terrible for dragging him out to a McDonald’s, but he laughs it off. I guess he really has mellowed out.

Bitten by the F&B Bug

It’s my (unscientific) hypothesis that once you’ve been bitten by the F&B bug, there’s no cure. Even as your business shutters and you burn out from working yourself to the bone, you’ll always feel the itch to try again. At least, this is true for my family and Jason.

Despite the toll the industry took on Jason’s mental health—and his pocket—he’s raring to make a comeback.

His next venture is already in the works, he tells me, appearing genuinely stoked.

He’s taken out a $50,000 loan and partnered with chef Titus Chong, who’s worked in the kitchens of Odette and Claudine, to start a Japanese-style sandwich business called Wild Crumbs.

The venture, located at Biopolis, is still in the midst of renovation, and won’t be open for a while. But Jason has it all planned out. With the restaurant serving only breakfast and lunch for the office crowd on weekdays, he’ll coach boxing in the evenings and leave his weekends free for his wife and kid.

He’ll still be “working like crazy”, he says, but it’s a lot more stable and sustainable than his old ways.

It’s Just the F&B Business

If it isn’t already evident from my family’s and Jason’s stories, the F&B life isn’t for the faint of heart.

Aiming to make it big enough to worry about luxury car taxes? You’d be better off in a different industry. But if you’re passionate about food and a glutton for punishment, welcome to the party.

I used to think the effort we put into food spoke for itself. With the countless hours my mum spent hunting down the correct type of sugar to sweeten our cendol (if I tell you, I’d have to kill you) and perfecting the taste of the pandan jelly, there was no way our ventures would be anything but a roaring success. Right?

With two failed F&B businesses in my family’s rearview mirror, I can safely say that it’s never that simple. As an F&B operator, so much is out of your hands. No matter how hard you try, eking out a semi-decent living is the norm, and making it big is an anomaly that rests heavily in the hands of Lady Luck.

It’s easy for customers to react in disbelief and dismay when their favourite stalls shut down, but if you look at the statistics, thousands of stalls cease operations each year. It’s almost inevitable. In fact, I’m surprised that some of our heritage hawkers have survived decades.

That’s not to say that the F&B industry is all doom and gloom and shouldn’t be touched with a ten-foot pole. Even though our cendol business never really took off, the trial by fire left my brother with some lifelong lessons.

As much as it pains me to praise my own brother, his work ethic can’t be faulted. The kid whose report card used to be a sea of red is now capable of juggling online courses and a punishing hawker job. Who would have thought?

Then there’s my mum, who says she was “sad but relieved” when things came to an end. She’s always had a love for food, but running the stall left her with precious little time for herself and for gastronomic experimentation.

These days, she’s settling back into the housewife routine, whipping up a storm in the home kitchen instead of churning out bowls of dessert. Honestly, I can’t complain.

And just because a stall closes, it doesn’t mean it’s the end of the road, nor a black mark on your record.

“Sometimes when we close, it’s not because we quit or we fail. It’s just to look for a better opportunity out there,” Jason offers.

“And those who gloat about people closing, those who claim that people fail, they’re probably sitting behind a desk and working a nine-to-five.”