All images courtesy of NUS Press, unless otherwise specified

“The later history of the PAP is the harder one to bring to life,” quotes 48-year-old historian Dr Shashi Jayakumar on what founding prime minister Lee Kuan Yew said to the authors of Men In White, a 2009 book on the PAP’s history focusing on the struggles towards independence in the 1950s and 1960s.

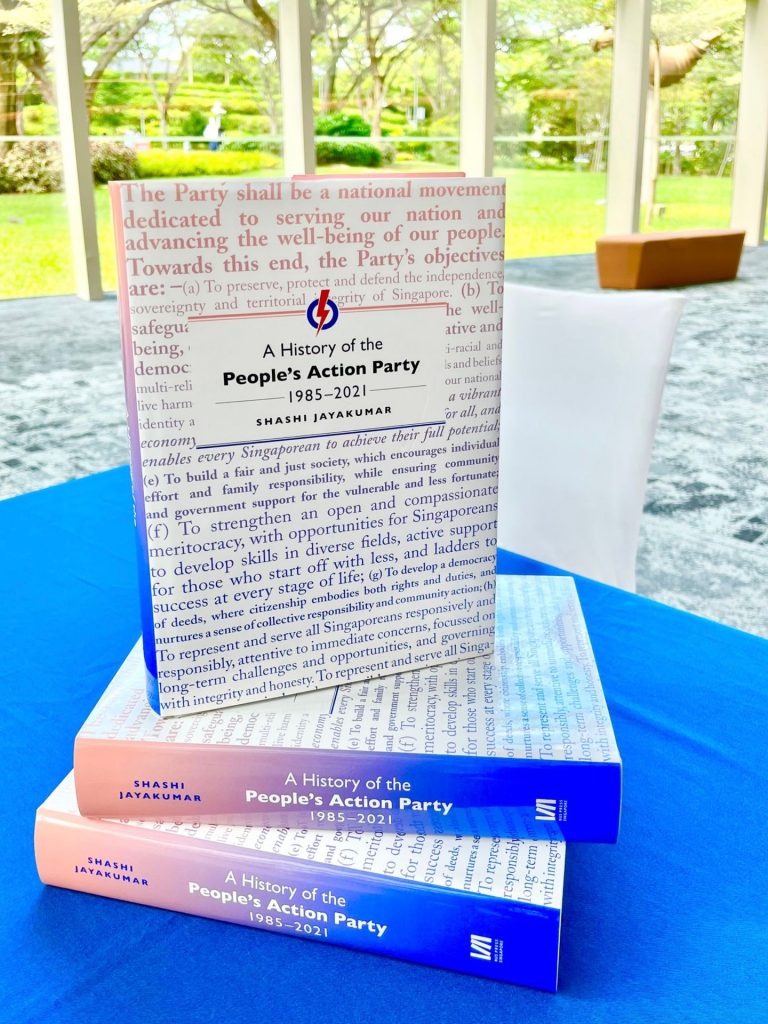

Dr Jayakumar is the author of A History of the People’s Action Party, 1985-2021, a newly-released book that records the party’s history from 1985, the time of the first political transition from the Old Guard to the new. Mr Lee recognised that once the party was in power and Singapore’s immediate survival was tended to, the country’s day-to-day running would become less exciting.

Still, writing this historical tome wasn’t going to be easy for Dr Jayakumar, who was asked by Mr Lee to write the book after the watershed general election of 2011. Unfortunately, the statesman didn’t live long enough to read Dr Jayakumar’s autobiography of the party as he died in March 2015. It’s a regret Dr Jayakumar took pains to mention in his book launch speech.

Indeed, this book reads less exciting than many other local history literature on the market. Thanks to our history lessons in school, many of us will recall the events from the 1960s experienced by the PAP: merger with Malaysia, communal riots, struggle with the leftists, and eventual independence. The history buffs among us would rattle off even more events, like Operation Coldstore or when then PM Lee Kuan Yew was almost overthrown by party defectors in Parliament.

There’s also something to be said when the later years are often classified as “politics” rather than “history”—the former perceived as mundane and predictable in the Singapore context. Inner deliberations and how the party governs after 1985 are thus less well-known, even though many of us have lived through this period.

The thick footnotes tell a story, too

Dr Jayakumar doesn’t intend for this book to be a bestseller. That it’s ranked seventh on The Sunday Times bestseller list on Jan 16 is a sheer happy coincidence.

While he’s ready to leave the book for others to judge, Dr Jayakumar says it suffices for the book to become a reference work for certain aspects of how the PAP governs in matters such as policy-making.

It is also why footnotes, bibliography, and appendices take up almost half of the book’s 782 pages. It’s thick because besides mentioning the sources, Dr Jayakumar elaborates extensively on the contexts and anecdotes which didn’t make it into the main chapters of the political publication.

In fact, some of the book’s most exciting nuggets are among the references, such as the depth of animosity between Lee Kuan Yew and opposition politician J.B. Jeyaretnam on page 144.

A historian by training, Dr Jayakumar is determined for every argument and claims to be backed up. “This is not a normal book. I was given access to privileged sources, both in the party and policy side of things, so I have to list all of them,” he shares.

Interview techniques

Readers would find that among the privileged sources listed in the book, is a list of people interviewed by Dr Jayakumar from 2011 to 2021. The list includes former and serving PAP politicians and diplomats like Professor Chan Heng Chee.

Of the 62 interviews conducted with named individuals, 22 were conducted after Lee Kuan Yew’s passing in March 2015.

Still, although Dr Jayakumar is the son of former deputy prime minister Professor S. Jayakumar and had Mr Lee’s blessings to write this book, not every door was opened to him automatically.

He shares that the book took so long to write because he had to persuade interviewees such as Mr Ong Pang Boon, the sole-surviving minister from the first cabinet, to speak freely and fully. This is despite Mr Ong being the only person pointed out to Dr Jayakumar by Mr Lee himself, to share information about the 1980s when he was still a party heavyweight.

Dr Jayakumar took years to coax him before the media-shy Mr Ong agreed to go on record on Jan 9 2020. He was amongst the last few interviewees Dr Jayakumar spoke to.

“Part of the interest is to establish the initial contact and then relationships. Over time, in one or two cases, we even develop friendships. Sometimes, only by building up trust can you speak to them,” Dr Jayakumar says.

It wasn’t easy for him to go straight to the point with the interviewees. Dr Jayakumar shares that the older generation came from an era where they were more cautious, especially if they didn’t know him personally.

Their wariness might have hailed from a time when local politics was deemed turbulent. These politicians either witnessed or experienced the overturning of loyalties, factionalism within the PAP, and political allies turning into foes, all due to differences in ideologies. As a result, it’s not easy to gain their trust.

“For some, you don’t even bring a tape recorder along, just take them out for coffee or lunch repeatedly, build up trust, and then you establish ‘okay, you said this and that at an earlier meeting, can I use this?’ before publication.”

Even so, not everyone was willing to share their stories with him. Dr Jayakumar does not explicitly say so, but based on the interview with him, it could be that some old retired PAP MPs were still bitter and resentful over the fast pace of political renewal in the 1980s and therefore declined to speak.

This whole kerfuffle over renewal, be it among the leaders (with Ong Pang Boon and Toh Chin Chye disagreeing with the approach of renewal Lee Kuan Yew took) or the backbenchers, is mentioned in the earlier chapter of the book.

Dr Jayakumar also reached out to three key Opposition figures to have a broader perspective of the party. Still, only one was willing to share off the record while the other two declined to speak to him.

The ageing retired MPs

Another challenge for Dr Jayakumar was that many key players of the 1980s, which was the book’s starting point, are slowly fading away from the scene.

In the decade as he was writing the book, Singapore mourned the death of first-generation leaders such as Lee Kuan Yew (2015), Toh Chin Chye (2012), and Othman Wok (2017). More recently, on Boxing Day last year, Phua Bah Lee, a PAP MP from 1968 to 1988, died at age 89.

So, when Dr Jayakumar started his research, he quickly contacted the older politicians first after poring through the newspaper archives and parliamentary records.

Racing against time, he quickly reached out to former MPs such as Lau Ping Sum, Tang See Chim, Dr Ow Chin Hock, Aline Wong, Ng Kah Ting, and many others, all of whom are now in their 70s or 80s, within the first two years of the book’s research.

Some individuals Dr Jayakumar interviewed are already old and frail. So even when these politicians agreed to go on record, some of them struggled to recall specific events from decades ago to fill the gaps in the book.

“Memories fade and change, and sometimes the memory of a certain incident can be quite different. That’s the nature of memories and we have to reconcile what actually happened to triangulate certain things,” Dr Jayakumar says.

“We are trying to be as accurate as possible and not take the most sensationalist version of something that has happened.”

If things had gone his way, Dr Jayakumar wishes to speak to more politicians from the pioneer generation so the historical record can be more thorough. But, sadly, many had already passed from the scene, while others (as noted above) had their reasons for not speaking to him.

The importance of a recorded history

His musings about the passing of a generation is telling of the crucial role the recording of history plays in the country’s institutional memory. In this case, the PAP has a special place in Singapore’s history, given that the ruling party’s history is analogous to the genesis of this nation.

It’s a pity, then, that besides Lee Kuan Yew, few pioneer PAP leaders shared their experiences and perspectives for this book.

While the National Archives have a collection of oral history recordings contributed by some of these old party stalwarts, whatever these politicians shared was limited by the scope of questions posed by interviewers. Even so, not everyone saw it fit to contribute. Visibly missing were ministers such as Goh Keng Swee and Yong Nyuk Lin.

In his remarks at the Dec 14 book launch, which he repeated at our interview, Dr Jayakumar said: “I hope in time to come, more (political veterans) will step forward to tell their stories, and perhaps to write them (personally), lest the part they played be forgotten.”

Perhaps leaving behind a record for posterity mattered less for the pioneer leaders, who were more concerned about running the country during the nation-building years. There could also be a national security concern if they had to share sensitive matters relating to the 1960s since some government documents from that time have yet to be declassified.

Dr Jayakumar says that Lee Kuan Yew wanted this book written because he feared that the younger generation didn’t understand the foundations on which Singapore was built nor would they appreciate what’s at stake.

If anything, Singaporeans should read this book to understand how, in the later years, the ruling party operated as a government instead of just as a political party.

Does Dr Jayakumar see himself as the PAP’s historian, then?

No, he says.

Mr Lee Kuan Yew didn’t give him any particular instruction or direction for the book. He had a broad leeway to write this book without any out-of-bound markers to adhere to.

Dr Jayakumar says he might not have taken up this project if the party had appointed him to write its official history. He says that no historian would like to be told what to or what not to write.

While party supporters can better appreciate the book’s content, it is the critics for whom this tome might prove most useful. At the very least, it gives a clearer understanding of the trade-offs, problems, and thinking behind the decisions made in the party.