Top image: Max Van Den Oetelaar/Unsplash

*Indicates use of a pseudonym

On a February day, I’d posted a call on Facebook for disabled interviewees to talk about systemic ableism in Singapore. It wasn’t long before a notification chimed—it was Melissa Ho, a neurodivergent writer pitching me an idea in her personal capacity. Ho’s work focuses on autism narratives and she’d found autism representation in Singaporean news concerning. Without the time to pursue the subject herself, she asked if I could do it, and offered to let me use her existing research as a starting point for mine.

Although I ended up agreeing to write on the topic, initially, as an allistic—that is, a non-autistic—person, I hesitated. Though a disability advocate myself, I worried I couldn’t grasp the concepts of ableism autistics face.

But as Ho said later, given autism’s stigma in Singapore, “we could be waiting a very long time” for an autistic Singaporean journalist who’s open about their autism to come along and opine on this issue.

‘Wait, what’s Autism?’

While Ho’s research invaluably informed the bones of this article, its information couldn’t replace interactions with autistic individuals—of which mine were limited. I knew that to truly learn about autism and autistics in Singapore, I had to speak with autistics themselves and glean more insights from individuals such as autistic researcher and multimedia artist Dr Dawn-Joy Leong.

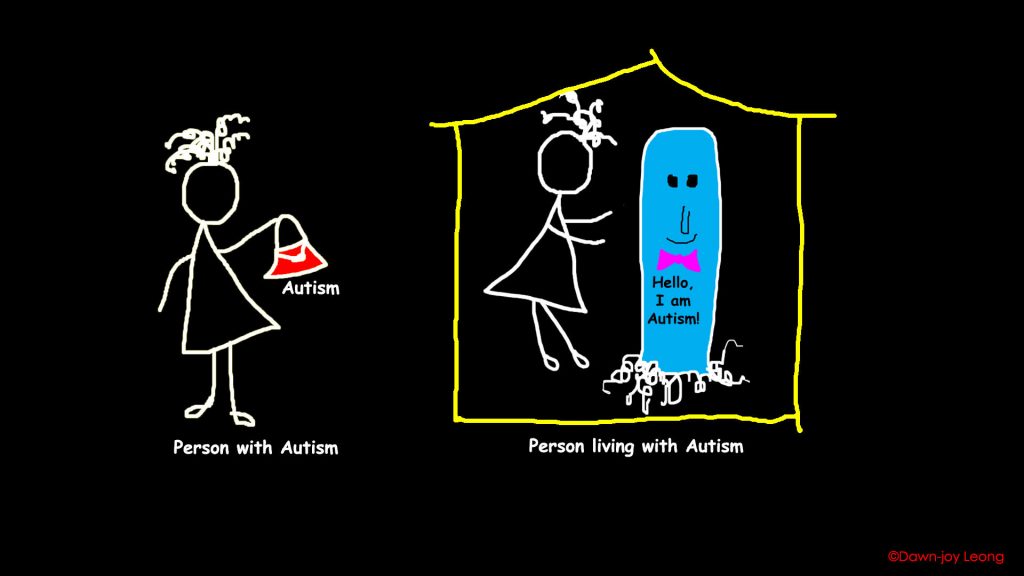

In her 2018 TEDx Talk, Dr Leong describes autism as “a difference of neurological function” and paints the autistic experience as a “rich, thriving ecology,” as opposed to a “disorder” in the medicalised lens. Autistics differ in their brains’ make-up and thus experience sensory sensitivities, communicate differently, think differently, and have repetitive behaviours.

“‘You are not your autism’ is as insulting as telling someone ‘you are not your brain.'”

And although traditionally a clinical diagnosis, autism is increasingly recognised as a type of neurodivergence thanks to scientific research and the efforts of autistic advocates such as Wesley Loh.

Dr Leong stressed the harm when allistics see autism as a medical aberration. “‘You are not your autism’ is as insulting as telling someone ‘you are not your brain,'” she says. “How can we possibly be removed from our brain? Autism is not a disease to be cured, not a set of weird behaviours to be fixed, not a curse from heaven.”

Loh adds, “Furthermore, it’s ableist to imply autism affects autistics’ ‘functioning’ as allistics tend to do.”

Considering Singapore’s autism research is relatively recent, and we’ve much societal progress to make regarding autistics, it’s impressive that some local organisations share Loh’s and Dr Leong’s opinions.

For instance, to welcome Autism Awareness Month in April, the five-organisation alliance of Autism Network Singapore posted a graphic on Facebook that reads, “[Autistics] are not disabled by autism. We just perceive the world differently.”

Autism representation in Singaporean media

Still, as encouraging as recent progress looks, it isn’t always reflected in mainstream Singapore media—likely because most of our society, including media members, are neurotypical and allistic.

When asked, Dr Leong and music producer Muhammad Arshad Fawwaz, both recipients of the Goh Chok Tong Enable Award in 2021, shared they have had positive experiences with media crews. Still, I’d later discover that their experiences aren’t universal.

They noted similar concerns with every autistic interviewee I spoke to—that local media groups overly portray autistics as charity recipients or “overcomers” of autism. Autistics with fewer support needs are also underrepresented.

Autism representation in Singaporean media isn’t diverse or accurate and relies on deficit-based stereotypes.

For Eric Chen, an IT specialist and the owner of iautistic, the problems he noticed vis-a-vis the autism representation in Singaporean media include an unbalanced focus on allistic caregivers’ perspectives over autistics’, particularly on how “burdensome” autistics are for caregivers.

He also cited the overemphasis on problems autistic people face, such as in relationships and mental health and autism “awareness” raising being superficial, therefore failing to impact society and challenge perspectives about autism.

My autistic interviewees shared that autism representation in Singaporean media isn’t diverse or accurate and relies on deficit-based stereotypes.

As a recent example, some cited Channel News Asia’s (CNA’s) Wired Differently documentary on an autistic child, Andric, and an autistic adult, Marcus. The documentary’s description says, “Andric saps [his mother’s] energy,” to start.

Moreover, Marcus’ autism is framed as what makes him potentially violent rather than addressing the abusive emotional punishments from his step-father.

The documentary’s approach reflects a continuing tradition of misunderstanding autism in Singaporean media.

Wondering if Singapore’s autism representation has shifted over time, I scoured the National Library Board’s digital newspaper archives and traced mentions of autism to the 1970s.

My search ultimately showed local news has steadily improved autism representation within the last 50 years. Still, its adherence to a medicalised lens of autism inhibits further progress.

Learning to listen to autistic voices

Unsurprisingly, media members may have difficulty shedding old views unless we have autistic voices in writers’ rooms. I wasn’t aware how much Singaporean media impacted my biases until I interviewed the anonymous non-speaking autistic poet known as fifi coo.

Because he relied on an alphabet board, I didn’t expect the insightful eloquence of fifi coo’s responses—despite my own reliance on text communication because of my impaired speech.

Not only that. I assumed, from the overuse of autistics melting down in local media to generate “sympathy,” that sensorial sensitivity hindered autistics’ lives. fifi challenged my assumptions.

“Being autistic made me sensitive and able to feel the emotions of people around me,” fifi shares. “This helped me understand and learn that feelings affect people and make them behave in certain ways.”

Knowing society underestimates non-speaking autistics, I asked what he’d say to anyone assuming his words aren’t his. “[I do not] care if people don’t believe I have a voice,” he responds, with a tinge of humour and self-assurance. To him, his voice to his family and healing is “more important than what others think or believe” about him.

Overseas researcher Rachel Chen, a Singaporean pursuing a PhD in Special Education at the University of California, Berkeley, and San Francisco State University, has observed a “growing paradigm shift” towards pro-neurodiversity. Chen has, over the past decade, studied the everyday interactions of non/minimally-speaking autistic children and adults, designing interactive environments centred on music and movement.

“In the US, personal accounts by autistic people have been counter-narratives towards common ideologies around autism,” Chen explains. These accounts by non-speaking autistic advocates like Naoki Higashida and Matteo Musso, Rachel elaborates, include various writings in literature, and, more recently, academia.

“When we presume communicative competence with non/minimally-speaking autists, we can begin to embrace the different ways they interact with others,” says Chen.

A question of ethics

Beyond honing skills of listening and considering autistic voices when writing on news that affects the community, there is also the issue of journalistic ethics.

Eric Chen warns autistics about potential dangers if one is unequipped to work with journalists. He had experienced incidents where his information was mishandled, and his reputation damaged when he was doing advocacy work.

Chief of the problem is not requiring journalists to get approval from interviewees on the accuracy of their quotes before the story is published. While many mainstream broadsheets don’t demand this as an official ethical guideline, other international publications practice such due diligence strictly.

Xie Yihui, a fellow disabled journalist and the former Editor-in-Chief of Yale-NUS’ student publication The Octant, attributes her practice of asking interviewees to approve her portrayals of them through hearing how some mainstream journalists misrepresent individuals from small communities in Singapore—disabled and non-disabled.

“I’ve heard from many of my schoolmates that their quotes got twisted when mainstream media interviewed them about their lives at Yale-NUS,” she says.

This isn’t to say no mainstream Singaporean journalist cares enough to get accurate quotes and cross-check them for factual fidelity. After I reached out to six other journalists for insights into mainstream newsrooms, finally, one reporter of a decade spoke with me on the condition of anonymity.

She explained that established companies might have internal guiding principles and ethics but are unlikely to update them regularly or emphasise them in staff training. The issue is heightened in smaller publications with less capacity for either.

She added, “I think it can only be a good thing for a news company to be transparent in its reporting policies and ethical guidelines and make them available for people who might be interested […] it could improve [the company’s] credibility as a whole.”

Chen also recalled his involvement in a CNA commentary that many autistics praised. “I felt [the journalists] were sincere in listening, even clarifying with me about some points that may sound controversial or were unsure of how to interpret what I said. Some interviewers rush to finish their interviews and don’t take the time to understand their subject.”

Journalism as allyship

Singaporean journalists must do better. By refusing the marginalised the respect and voice they deserve when working with us, we cut off parts of our communities, and parts of ourselves in turn.

We deny them opportunities to shape culture, something a 2016 Scientific American article—penned by a developmental paediatrician, a developmental scientist, and an anthropologist—states is a powerful influence on “the very definition of autism.”

When asked how autism representation can be improved in Singaporean media, autistic psychotherapist Chan Shu Yin suggests the media “shows [autistics’] strengths and good sides, and not just the flaws and the weirdness.”

“Point out that maybe it’s true that some things in society or habits of neurotypicals can be questionable or have negative consequences, and it’s not that they are absolutely right and autistics are wrong by default,” she says.

“We shouldn’t have to fear revealing our [autism] to peers or lecturers.”

Chan is one of many who didn’t know she was autistic until adulthood in part because Singaporean culture hyperfocuses on autism’s “deficits”. By the time she found out she was autistic, she’d buried parts of her true self by “masking” her autism to survive socially. Despite the stigma, her diagnosis empowered her to “understand [she isn’t] faulty or broken, simply born different.”

Still, Loh explains, “It imposes more barriers when people think of autism negatively. It’s difficult to have my words taken seriously by the public.” He believes that Singaporean media often reinforces autism’s stigma making his advocacy efforts a Sisyphean task. Dr Leong and Eric Chen expressed similar sentiments of advocacy fatigue.

The stigma toward autism affects autistics’ interactions with institutions and peers, too, as a Social Work undergraduate, who asked to be known as Anthony*, has had difficulty finding peer support throughout higher education.

“The media should help autistic students advocate for a systemic elimination of stigma in education—institutions should ensure robust peer support networks,” says Anthony. “We shouldn’t have to fear revealing our [autism] to peers or lecturers.”